In this episode, fellow Story Grid editor Valerie Francis and I analyze a scene from Lock and Key, the first book in the Essence Riven Trilogy by Emily Bowie. We talk about the crisis question in a scene, a moment when a question arises for the POV character.

To keep the story moving, your scenes should turn. To be more specific, they should turn so that it becomes more or less likely that the protagonist will get what she wants and needs. When this turn happens, and the character faces a point of no return within the scene, she must figure out how to respond. This week’s editorial mission will help you identify or add these questions and make them stronger to support your story.

Listen to the Writership Podcast

This week's submission contains some violence.

About Our Guest Host

Clark is taking a well-deserved break from the podcast, so today we're joined by Valerie Francis, author of fiction for women and children and Certified Story Grid Editor. You can find out more about Valerie here.

Wise Words on The Crisis Question

“The dilemma confronts the protagonist who, when face-to-face with the most powerful forces of antagonism in his life must make a decision to take one action or another in a last effort to achieve his Object of Desire.”

Mentioned on the Show

During the episode, Valerie and I talked about Rubicon moments. This is a reference to Julius Caesar's crossing the Rubicon, an event that precipitated the Roman Civil War. When his term as governor over Gaul and Illyricum ended, the Roman Senate ordered Caesar to disband his army and return to Rome. The Senate was clear that he should not bring his army across the Rubicon river, the northern boundary of Italy. Caesar decided to disregard the order. He is credited with saying alea iacta est (the die is cast) as his army marched through the shallow river. Today you will sometimes hear the phrase "crossing the Rubicon" to mean passing a point of no return.

I also mentioned that the Rubicon moments are more painful than what happens before or after, and that is discussed in this article. Is this just a tangent? I don’t think so. Our understanding of human nature and psychology can inform the decisions our characters make whether they are under extreme stress or not. Characterization is best done by demonstrating the characters choices. As Aristotle said, “We are what we repeatedly do.”

The Writership Index

Listeners have asked for an index of the podcast episodes and the topics discussed, so we've put together a Google spreadsheet containing details of each episode, its airdate, author name, story title, genre, story type, published location, author website, and topics discussed. Get access to the spreadsheet here.

Join the Writership Book Club!

Join now and you'll get access to a recording of October's meeting, in which we read stories from The Best Science Fiction and Fantasy of the Year, Volume 10 and analyzed them the way Leslie does for a Story Grid Diagnostic. You’ll also be able to join us for our next (online) meeting this Thursday November 16. Find out more at Patreon.

Editorial Mission—Crisis Questions

The crisis question is a dilemma the POV character faces that arises from the turning point. To raise the stakes, this should be a best bad choice or a choice between irreconcilable goods. In other words, it’s not an easy choice and the character sacrifices something when she makes it. To a certain extent, you’ll want the decision to be irreversible as well—or more specifically, the decisions should become progressively more irreversible as you approach the big moments in the story. If she could reverse the decision in the next scene that diminishes the stakes. We care about the character for lots of reasons, but a big part of that is what she risks when she makes a choice in these moments.

To determine whether you have a strong crisis question in your scene, review and see if it changes from the beginning to the end. If you can’t identify how the scene changes, check out the show notes for episode 119 on scene value shifts. If the scene does change, look for the moment when it turns. Does the POV character face a dilemma after coming to a point of no return? Does the dilemma create a best bad choice or choice between irreconcilable goods? If not, consider how can you revise the scene to bring it to that point. Is the decision too reversible? If so, how can you make it harder to call a do-over soon after making the decision has been made?

If you get stuck on this editorial mission, please leave a comment or write to me.

Editing Advice to Our Author

Hi Emily,

Thank you so much for sharing your submission! You have a great premise that promises lots of conflict and a character who isn’t going to go along quietly, which will pull the reader right into the heart of the story.

In terms of next steps for the scene in front of us, I recommend focusing on the turning point and crisis question of the scene. But what do I mean by that? How did I reach this conclusion? And what are some options available to you to make the scene more powerful? To answer these questions, I’ll walk you through the scene analysis. This is revised somewhat from the discussion in the episode because, as is sometimes the case, mulling things over yields greater clarity. This is one way to review a scene when you know that it could be made stronger, but you’re not sure how to identify a potential problem and what to do about it.

What’s literally happening?

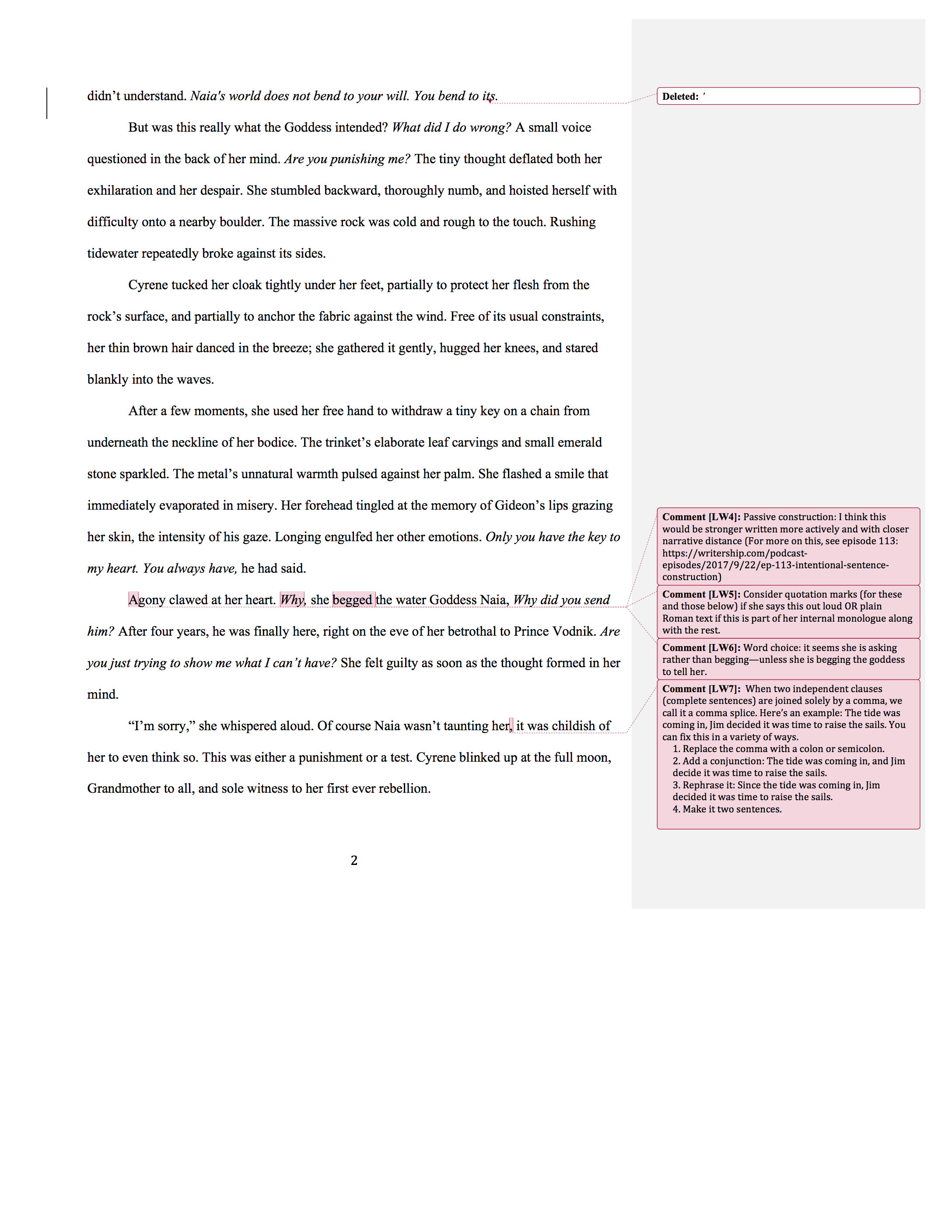

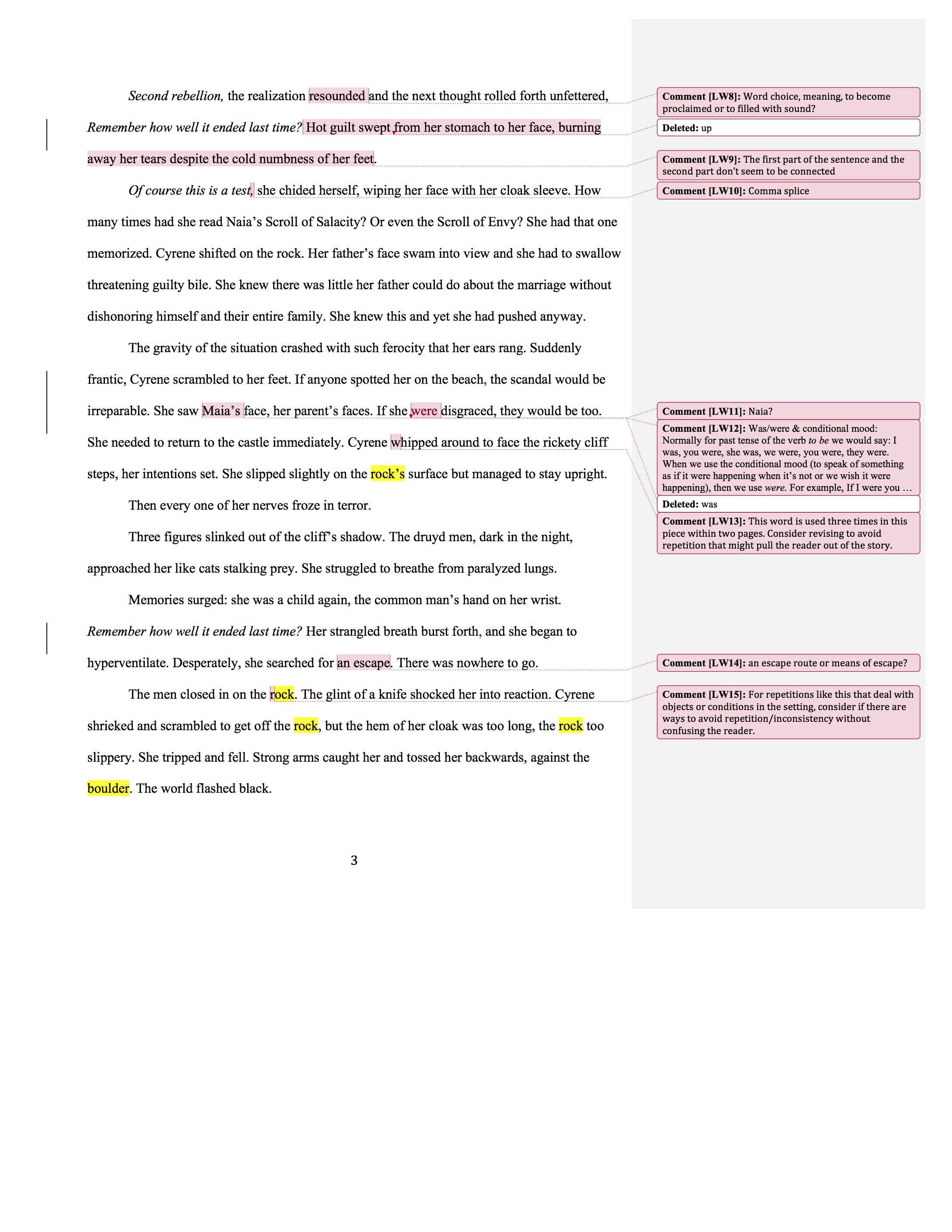

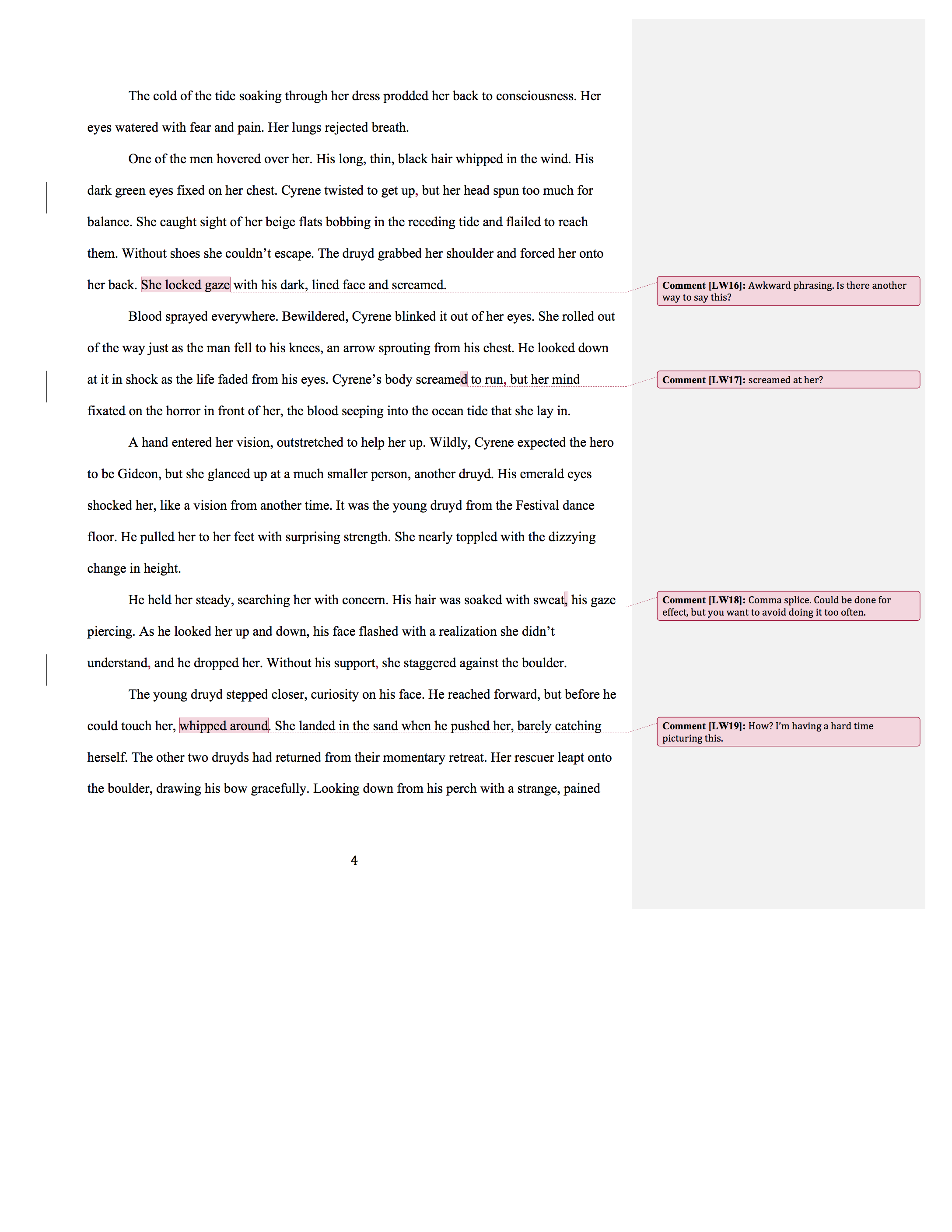

First, we look at what’s happening in the scene on the surface. Cyrene snuck out of the castle at night, realizes how this could hurt her family, and wants to get back without being noticed. She is attacked by three druyds, who seem to be after the key Gideon gave her, and a fourth druyd (presumably Cade) fights them off so she can escape.

What’s the essential action?

Second, we ask, what’s the essential action. With this inquiry, we want to understand the POV character’s motivation and what they actually do to achieve it. This had us a little stumped because our initial conclusion about the essential action (that Cyrene is coming to terms with her situation or deciding what to do about it) doesn’t relate to how the scene turns (or how things change for Cyrene from the beginning to the end of the scene).

What Life value has changed for one of the characters?

Third, we look at the life value that has changed from the beginning to the end. This can be for any of the characters in the scene, and you narrow it down to the most important in the next question. Both Cyrene and Cade go from being uninjured to injured, and that is something you’d want to notice, but on reflection, it looks like the important life value change (based on what we have in front of us) is that Cyrene goes from being safe and uncompromised to a precarious position with potential dishonor (for having been outside the castle alone at night).

Life value related to the main or global genre?

Cyrene is our POV character and protagonist, so it makes sense to focus on the change she experiences because it will most likely represent the scene change that brings her closer to or further from her story goal.

Inciting Incident:

This is the event in the scene that knocks the POV character out of balance and represents a change to the status quo. My best guess is when she says this: “The gravity of the situation crashed with such ferocity ...” Until that moment, she’s wrestling with her thoughts, but not nothing has changed from when she came down the steps to the beach. When she recognizes the danger, she’s placed herself and her family in by being out at night, the desire to get back inside without being caught arises.Progressive Complication:

Progressive complications are the increasing difficulties the character faces in achieving her goal in the scene. Cyrene wants to get back inside without being caught, but three men come out of nowhere. Then they close in around her. She tries to run, but her cloak gets in the way and she slips on the rock and passes out.Turning Point:

This is the point of no return when the scene turn happens, and the POV character faces a question. When Cyrene wakes up, the men have her.Crisis Question:

This is the question the POV character faces that arises from the turning point. To raise the stakes, this should be a best bad choice or a choice between irreconcilable goods. In other words, it’s not an easy choice and the character sacrifices something when she makes it. To a certain extent, you’ll want the decision to be irreversible as well—or more specifically, the decisions should become progressively more irreversible as you approach the big moments in the story. If she could reverse the decision in the next scene that diminishes the stakes. We care about the character for lots of reasons, but a big part of that is what she risks when she makes a choice in these moments.Cyrene doesn’t have an opportunity to face a best bad choice because Cade attacks the others and tells her to run. In the episode, we talked about how the question to run or not isn’t a best bad choice, but rather, the obvious choice—at least based on what we see before us (You may have revealed other facts in the scenes that lead up to this one that would change this conclusion). How could you make this a stronger dilemma? If Cyrene had a strong emotional attachment to Cade and feared for his safety, that would be different, or if she absolutely couldn’t appear back in the castle without her sandals, that would also be different (but again, doesn't feel as strong).

If the story circumstances won’t allow her to be attached to Cade, she could consider giving up the key. You’ve established that this is precious to her, so it’s not that big a stretch that she would resist parting with it. It appears that the druyds who attack her want it, so it’s possible she could believe that the key might buy her freedom and allow her to get back to the castle. You could dial up these possibilities and have her wrestle with this decision, and it seems this dilemma would impact the overall story.

Climax:

This is the decision the character makes based on the crisis question and the action she takes in furtherance of the decision. If you were to take the route I suggest above or something similar, Cyrene could decide not to give up the key, that it’s too precious to her—but she might. Either way, she wouldn’t need to actually give up the key because Cade could still come to her rescue as part of the resolution of the scene.Resolution:

This is what unfolds after the decision and the character’s taking action on it. It can be causal, meaning that the character’s action precipitates action on the part of others (for example, the attacking druyds might knock her out and leave her on the beach) or it can be simply what other characters do anyway (Cade jumps in to save her). The final part of the resolution is that Cyrene runs when Cade tells her to and makes it back to the castle. A guard sees her, and she notices the blood on her feet and head then passes out. More consequences could flow from this, when she wakes up and based on what the guard does, but that is quite possibly exposition or an inciting incident for the next scene.A different but somewhat related point to consider concerns Cyrene’s change of heart about whether she should be rebelling (either the small rebellion of being outside the castle at night or the bigger issue of whether she should marry Prince Vodnik). The change seems to come as the result of her thinking and coming to her senses. It’s hard to be certain without knowing more, but I wonder if this change of heart (or coming to her senses or becoming resigned to her fate) could be more powerful if something in the environment or outside herself reminds her that her circumstances are probably a test.

I’ve included some copyediting suggestions within the submission, but you’ll want to save those until you’ve made any desired changes to the structure of the chapter.

Thanks again for sharing your submission and trusting us with your words!

All the best,

Leslie

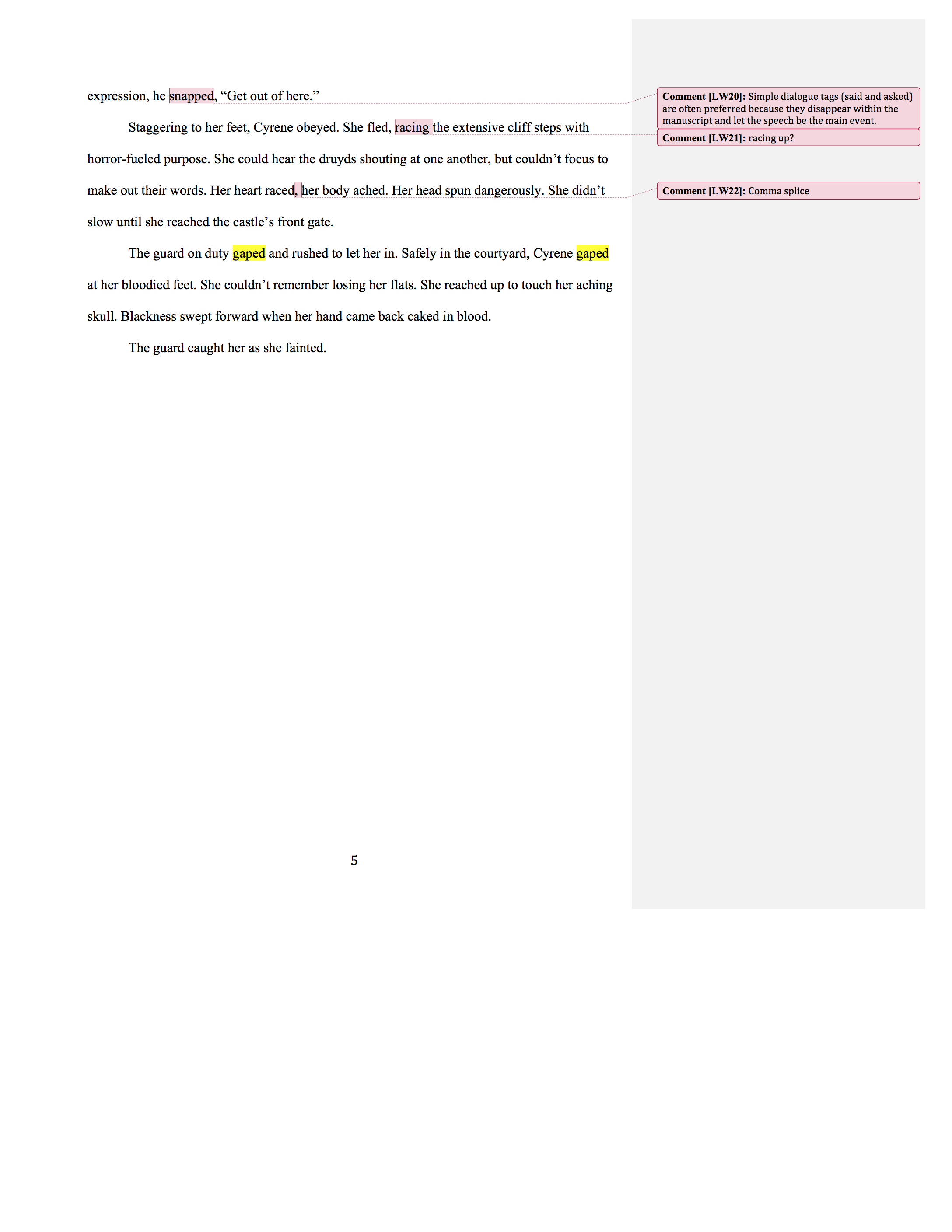

Line Edits for Our Short Story

Image courtesy of getstencil.com.