In this episode, fiction editors Leslie and Clark critique the first chapter of The Palace Thief, a YA fantasy novel by AR Richardson. They discuss omniscient point of view and why you should give it a try if you haven’t.

This POV option is often considered old-fashioned, but it offers flexibility and options that you don’t have with the other POVs. While it’s probably the most challenging, you might find that it’s the best vehicle for your story.

Speaking of options, Leslie and Clark have a fun editorial mission with lots of choices to help you experiment with the elements of this writing tool.

Listen to the Writership Podcast

Wise Words on The Omniscient Point of View

“[The Omniscient point of view] is the most openly, obviously manipulative of the points of view. But the voice of the narrator who knows the whole story, tells it because it is important, and is profoundly involved with all the characters cannot be dismissed as old-fashioned or uncool. It’s not only the oldest and most widely used storytelling voice, it’s also the most versatile, flexible, and complex of the points of view—and probably, at this point, the most difficult for the writer.”

Mentioned In The Show

It helps to look at examples of omniscient POV to see how others have mastered it. Jane Austen’s and Charles Dickens’s stories are great examples of older novels that employ an omniscient POV. But you can find more recent examples as well, including J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter series, Terry Pratchett’s Discworld series, the Earthsea Cycle from Ursula K. Le Guin, and Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials series.

Other authors who make this choice include Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Martin Amis, Tom Wolfe, and John Updike, but also The Book Thief by Markus Zusak is an example of a book with an omniscient narrator who is also a character.

Another example is From the Mixed-up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler by E.L. Konigsburg.

Clark mentioned that it helps to read and watch stories about storytellers, including The Adventures of Baron Munchausen.

Editorial Mission—Omniscient Point of View

This week, we want you to try the omniscient point of view. It can be tricky to master, but with all it has to offer, it would be a shame to avoid it simply because it’s hard. If you’re listening to this show, that’s probably not the kind of writer you are. Be willing to make mistakes and write a crappy scene in furtherance of your art. You may discovery that it’s perfect for your current work in progress or one in the future. If not, you’ll learn something about the craft of writing and yourself as a writer. Here are some options:

Review a scene from a story you’ve written in third limited or first POV. Rewrite it in omniscient POV. Put it away for a couple of days before you review it. Compare the two versions of the scene. What do you know now (about your story, characters, setting, etc.) that you didn’t know before?

Read a scene from a story you love written in omniscient point of view. Write a side story or scene (also omniscient) using the characters and setting. You can change what happens next, write a scene that happens “offstage” or create the beginning of a subplot that doesn’t already exist.

Watch a scene in a movie or TV show and write it as an omniscient scene.

Think of a real or fictional situation where someone is making a huge mistake and you know exactly what the person should do. Write a scene in omniscient POV in which your fears for that person are realized.

Write a modern day fable or fairy tale. Try starting with Pixar’s fourth rule: “Once upon a time there was ___. Every day, ___. One day ___. Because of that, ___. Because of that, ___. Until finally ___.”

Map out a simple scene with three characters goals that are in conflict. It can be as simple as a disagreement over where to eat. Write the scene three times, once from each character’s perspective. Then weave the three accounts together into one scene that includes what’s relevant to the story you want to tell about the scene.

Editing Advice to Our Author

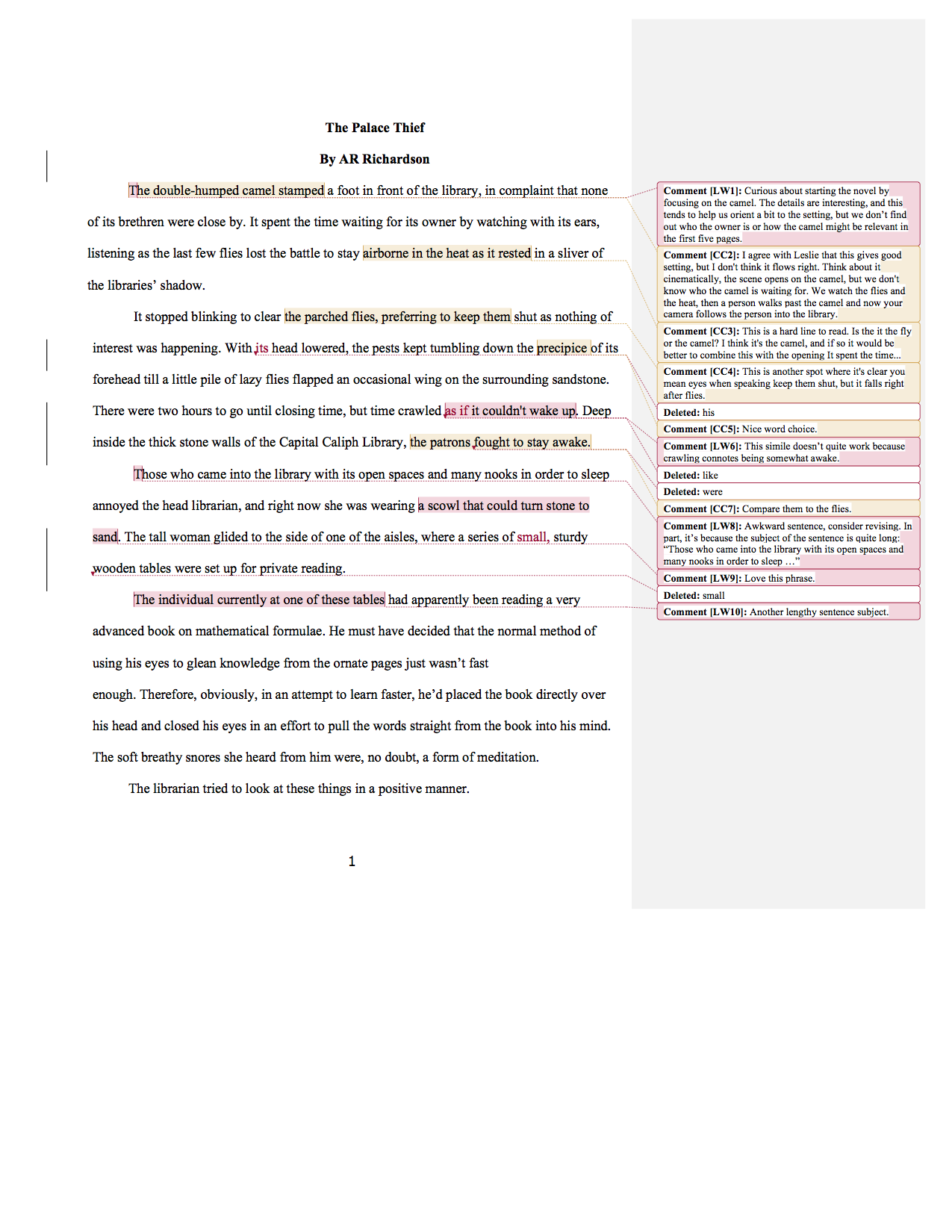

Dear AR,

Thank you for your submission! What a fun premise for a YA story with lovely descriptions and phrases. We feel curious about the characters, and the opening promised great conflict and humor.

We’re so pleased you decided to use third person omniscient POV for your story. Omniscient POV provides flexibility, but consider where you are shining a light for the reader’s attention. Focusing on the camel first could pay off later, but we can’t tell that from the scene we have in front of us. Consider what’s most relevant to your reader as you decide where to point the narrator’s camera.

Think of your narrator: who is she, what is her purpose in telling the story, what does she care about? From what vantage point is she telling the story? Understanding that will help you know what to leave out or put in, and how much time to spend on the elements.

One of the tricky things with omniscient POV is providing a smooth transition when changing focus. We recommend keeping narrative distance in mind (how close we are to the characters and their awareness and thoughts) and shifting focus gradually to avoid a jarring experience for the reader.

There are some great lines and imagery in the world, but the characters could use more consistency. They feel a little vague and seem to float in the room. One moment the reader forms a clear picture of the scene, and then one of the characters will suddenly be elsewhere. When that happens, the reader has to rebuild the scene in their mind. This happens when Munir has the book on his head, from the librarian’s perspective, but later is using it as a pillow. At one point it seemed the librarian was right next to Munir, but then seems to be farther away. If this is meant to show that the two characters have different ideas about what is going on, be really intentional about showing the reader what’s going on.

We can’t tell how this scene relates to the rest of the story, so you’ll want to check that it is directly connected to the main conflict in the story and does more than introduce these two characters and show us how they meet. It’s entertaining, but the opening scene should be working hard and accomplishing multiple tasks.

It could be just my (Leslie) personal preference, but I wanted to see more of the library, the building, the books, the furniture. It would be good to have a better sense of where we are in time within the novel as well. Speculative story settings don’t have to correspond to historical periods in the real world, but they tend to be loosely connected or derived from some time in the past or projected into the future as shown, for example, by modes of transport and communication. Think about how Steampunk happens in the Victorian era or much epic fantasy happens in a time resembling the medieval era. You can create the setting as you wish, but consider including more clues about what we can expect. The camel and scimitar give us some indication, and you may provide more in later scenes, but I wanted to mention this since it came up on my radar.

Thanks again for sharing your opening with us, AR!

All the best,

Leslie and Clark

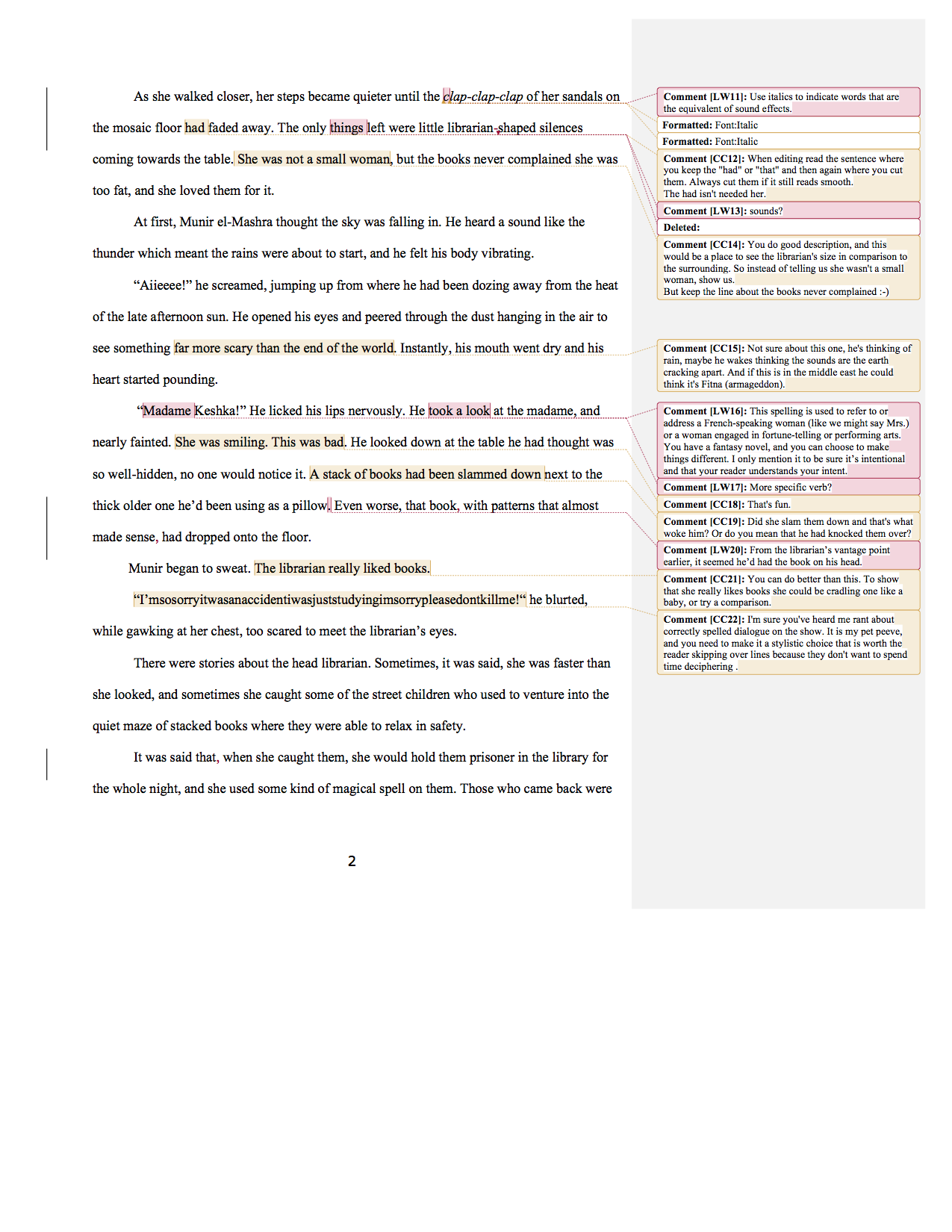

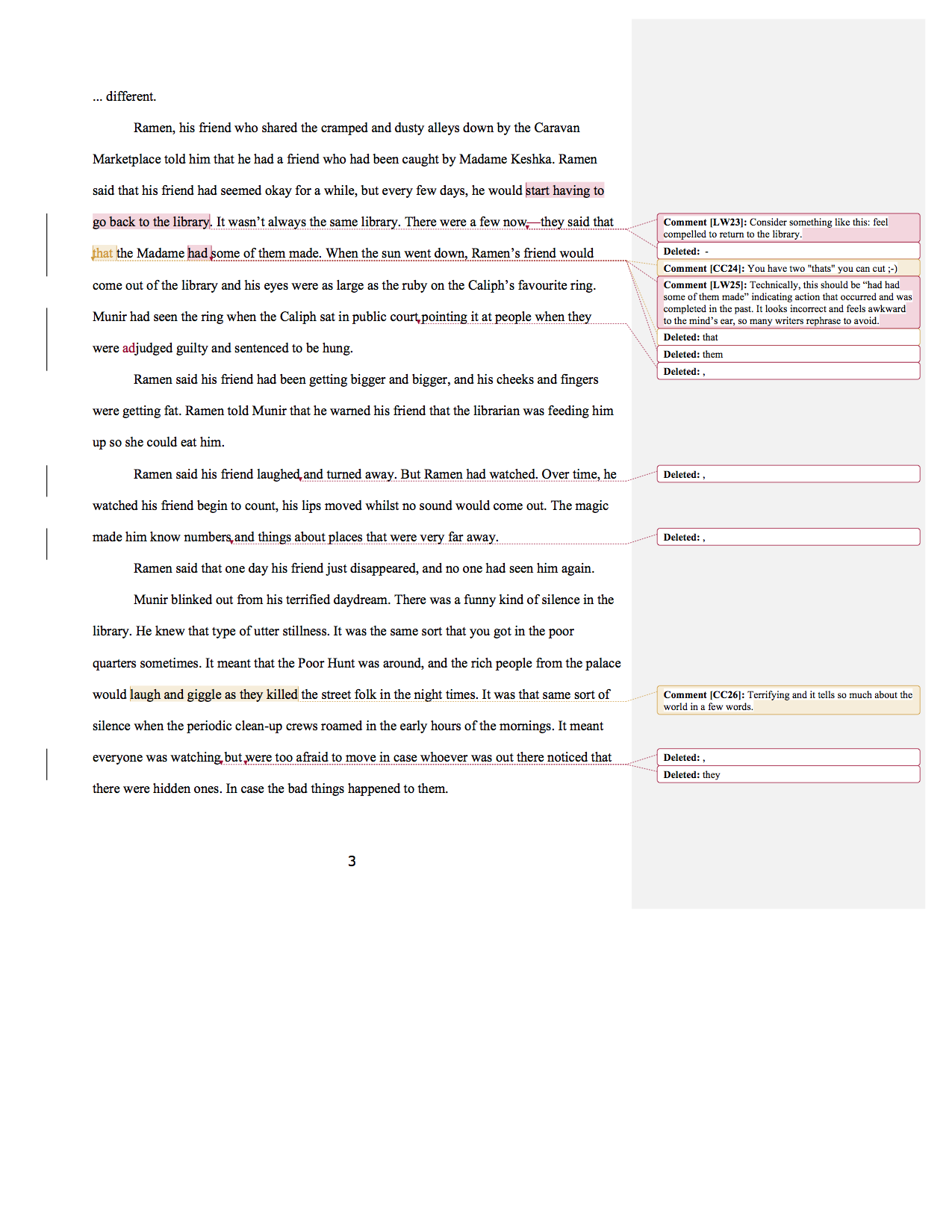

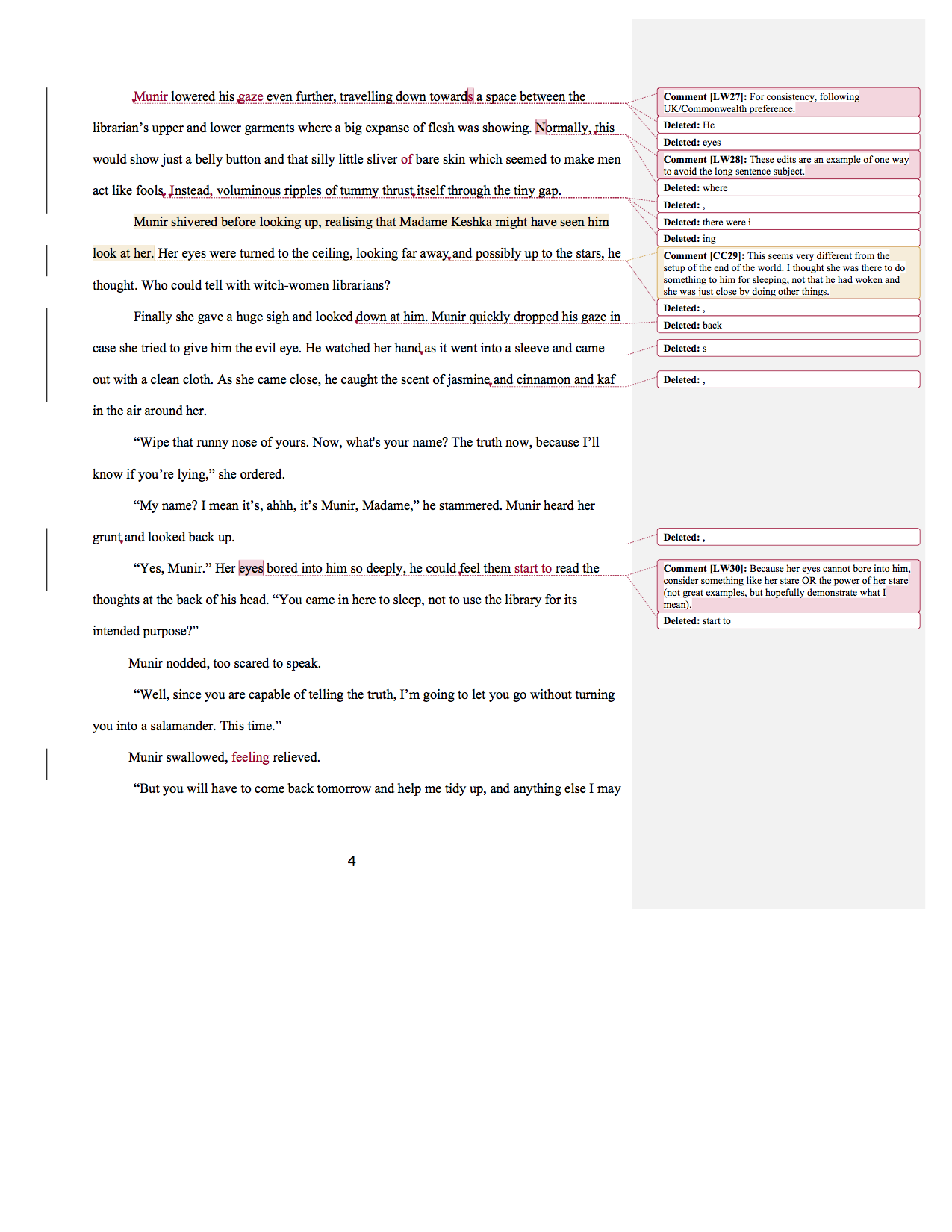

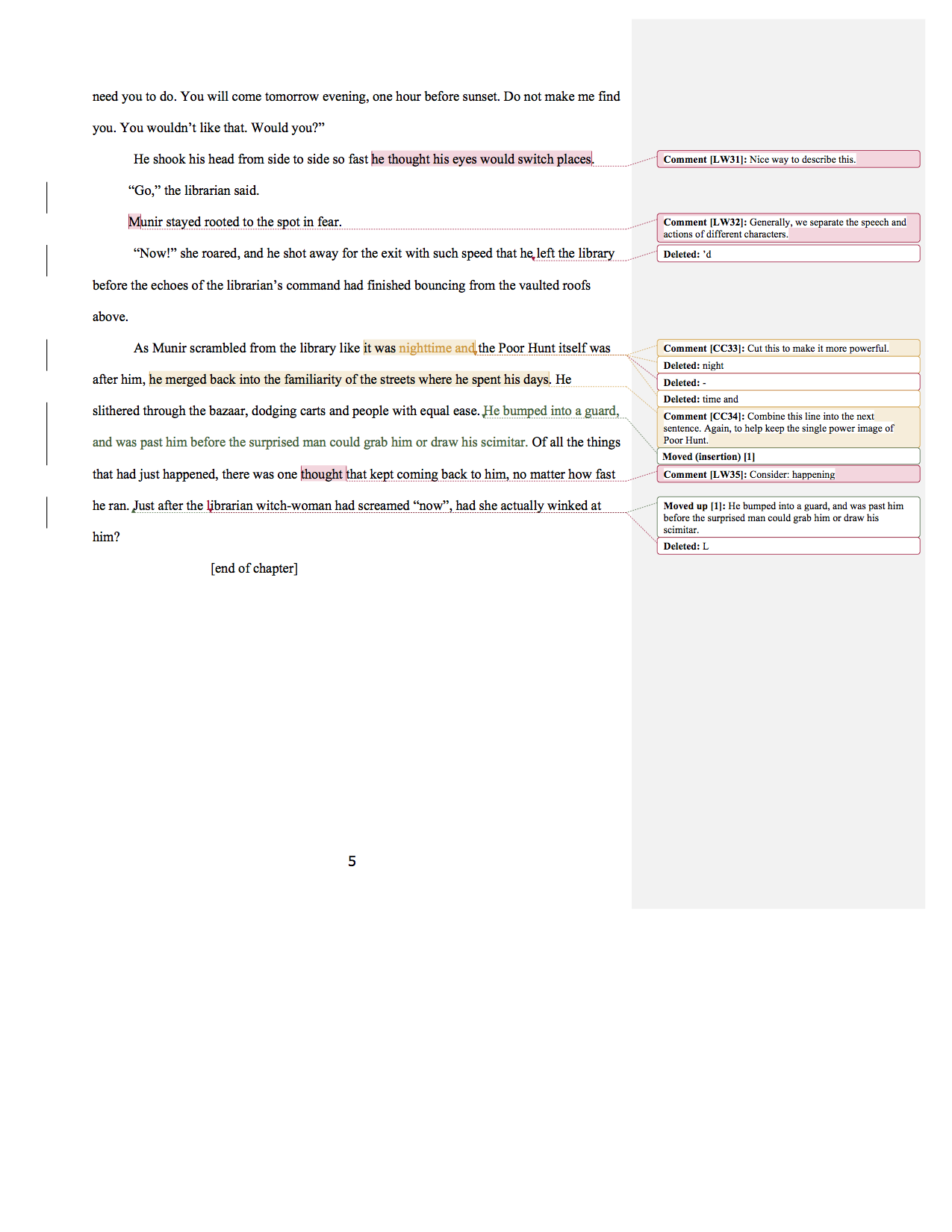

Line Edits for Our YA Fantasy Story

Image courtesy of [CREDIT GOES HERE]/bigstockphoto.com.