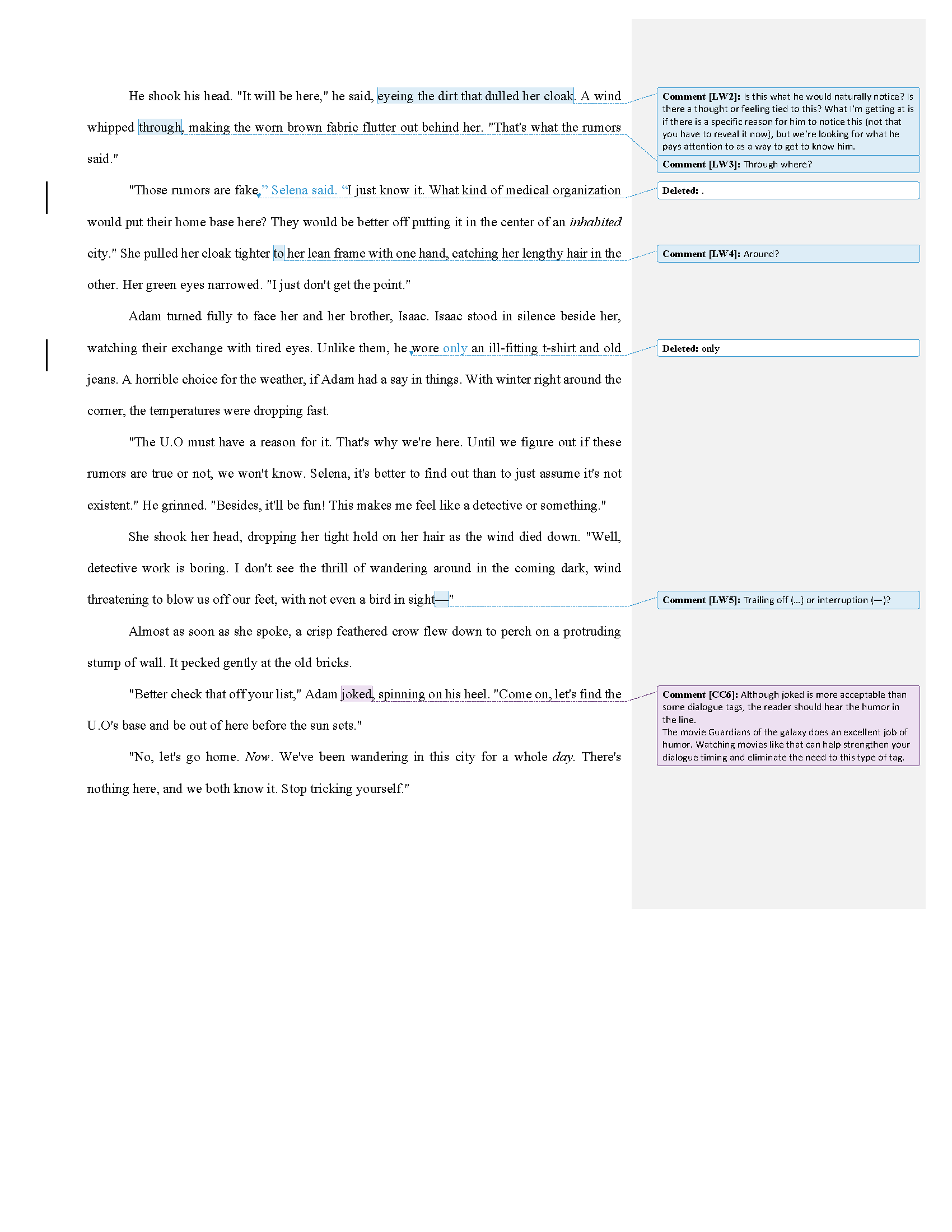

Description

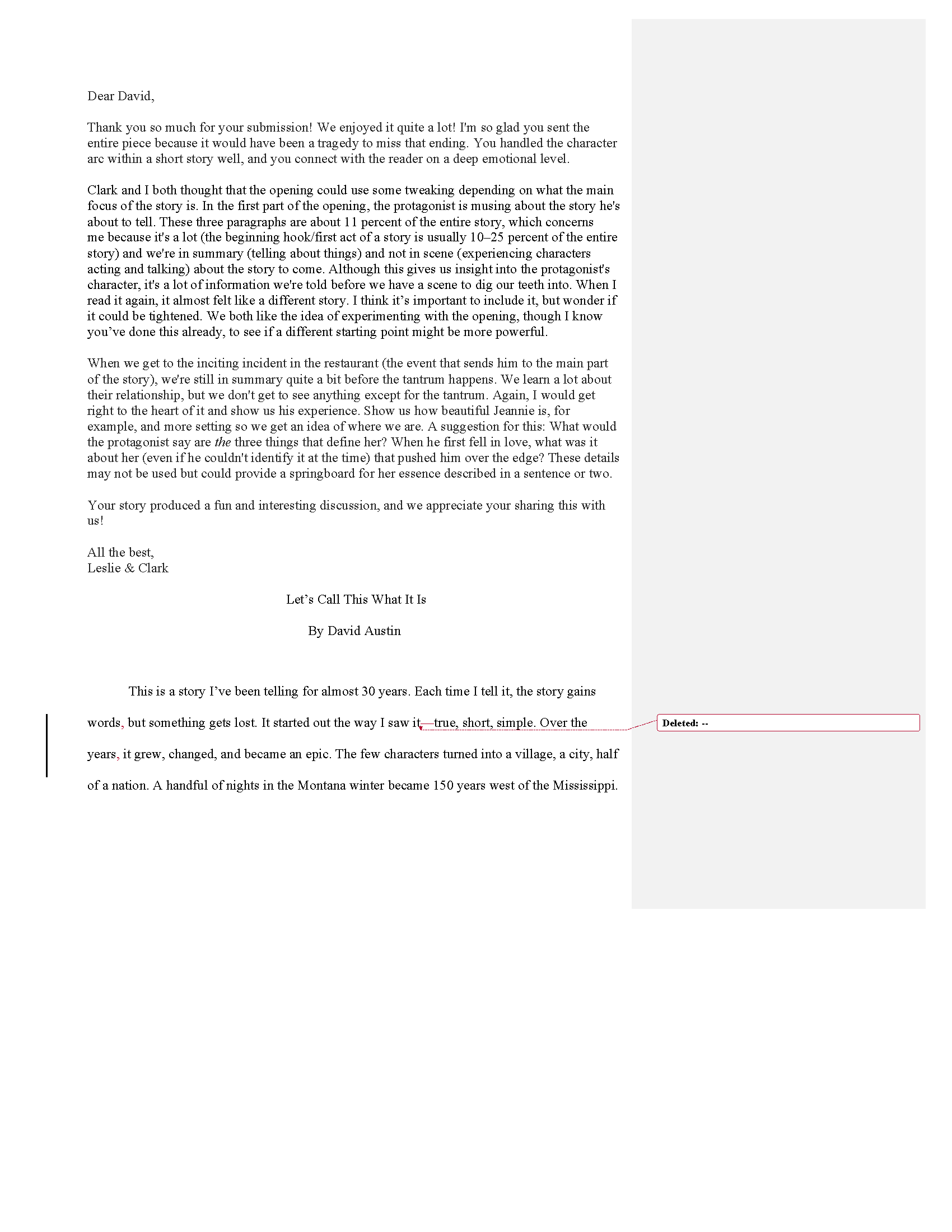

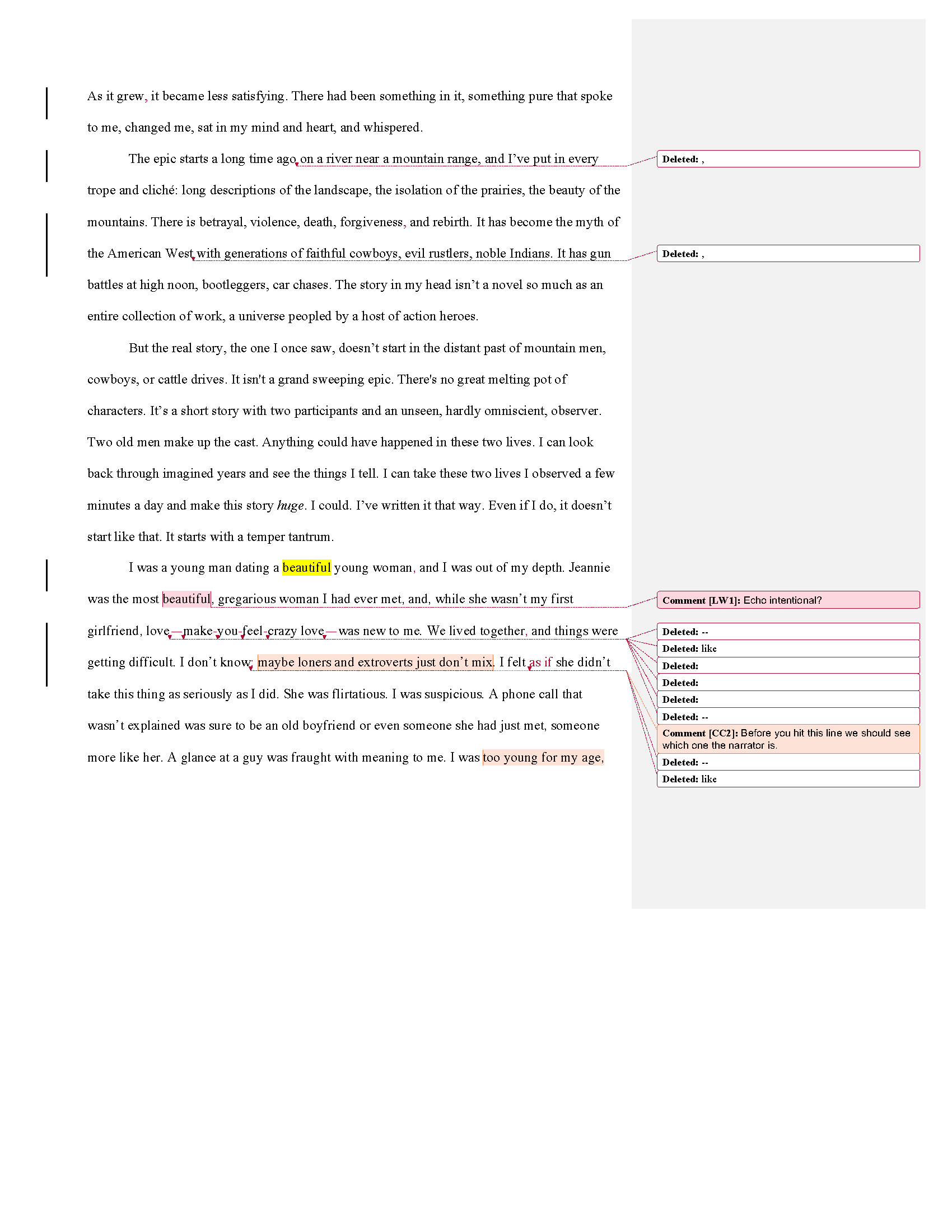

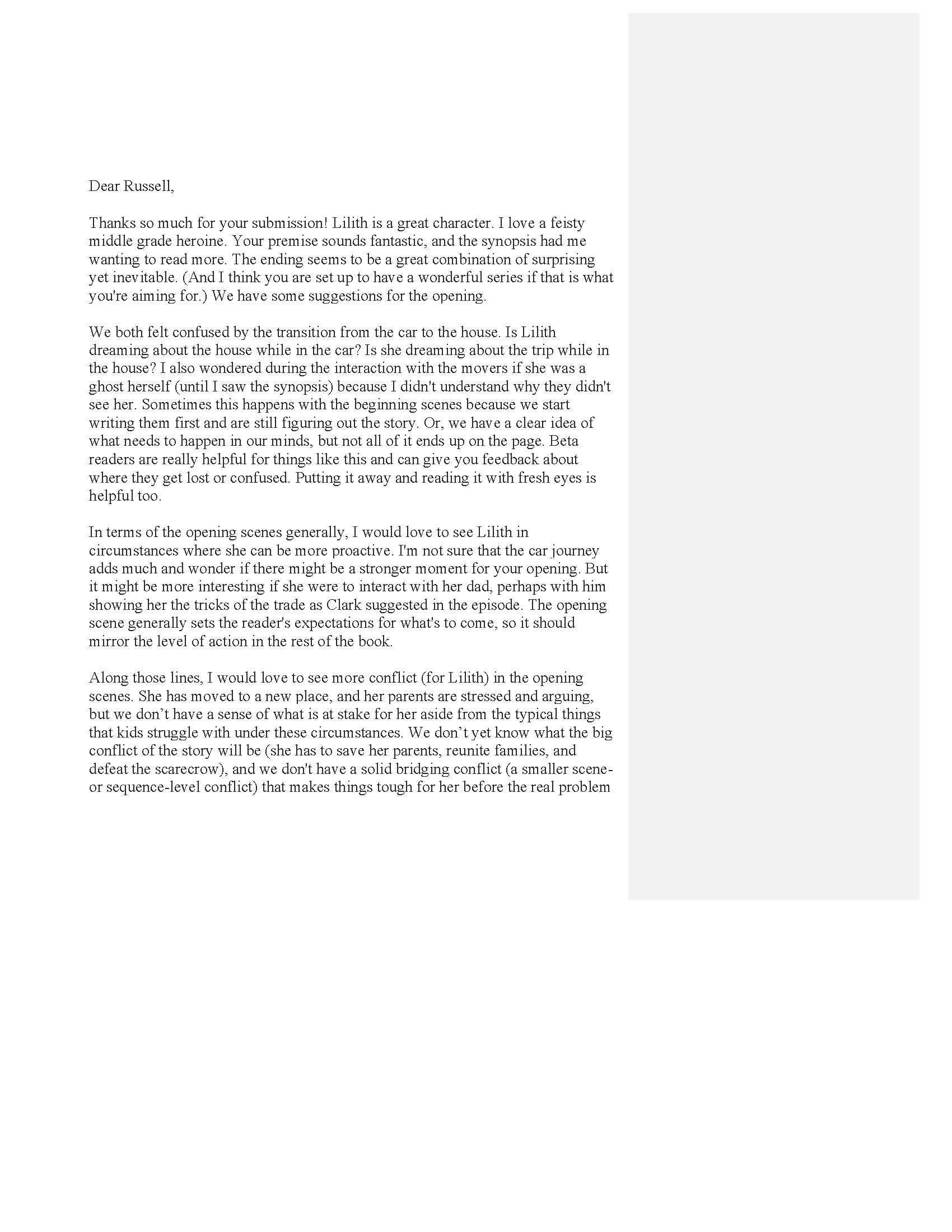

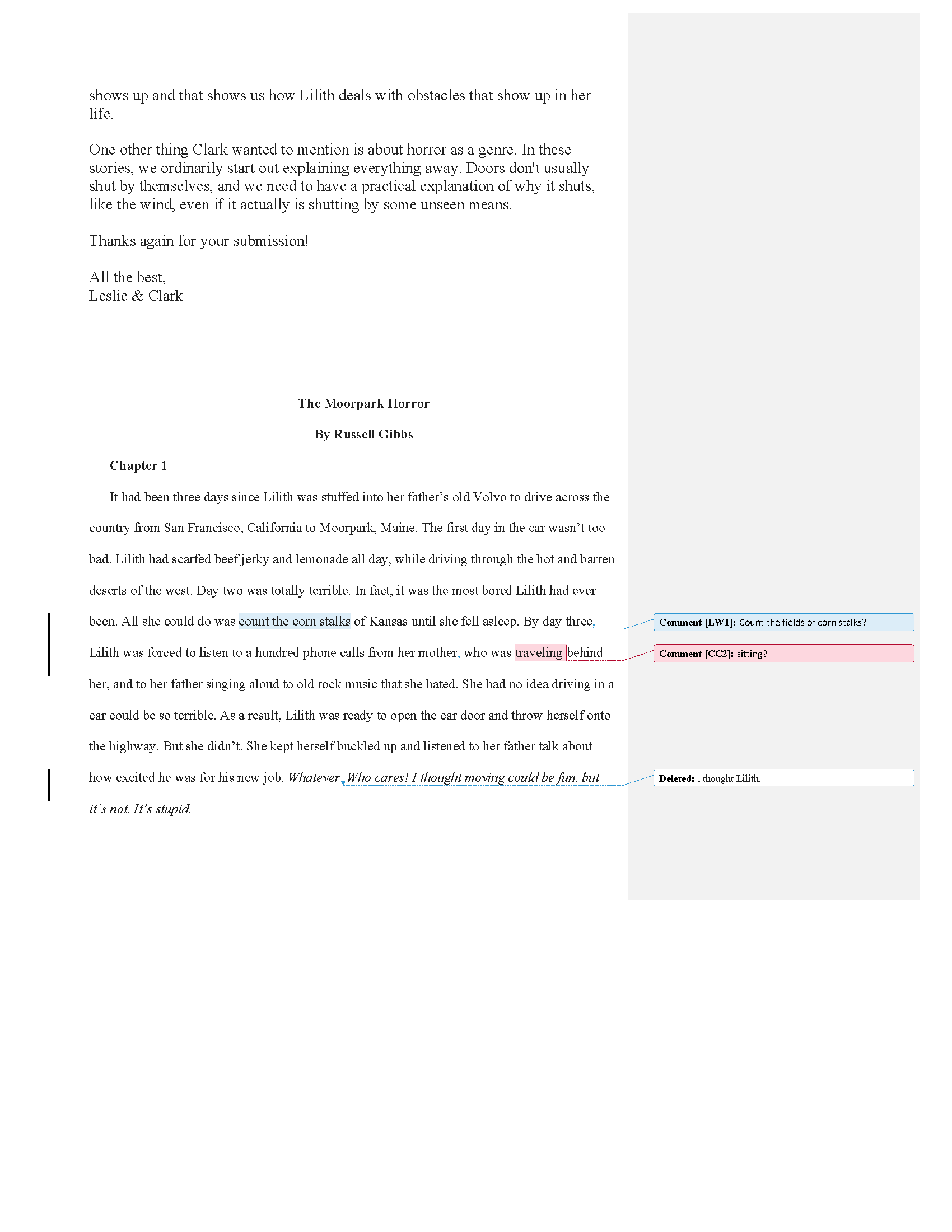

In this episode, Leslie and Clark critique the first chapter of The Pick Up, a LGBT romance novel by Allison Temple. They discuss genre, obligatory scenes in romance stories, and romantic conflict.

Listen Now

Show Notes

“But the Love Story is the long-term mother of all Genres. It’s not just about how to survive today; it’s about how to last a lifetime...and even how to gain a measure of immortality. Good old Marcus Aurelius has a measure of immortality, doesn’t he? His work still resonates today...probably far more than it did in his own lifetime.

Love story is the structure that instructs us on how to discover the meaning of our existence. Both as individuals and as atomic particles that bump into one another in a complex action and reaction that comprises the human collective unconscious. Don’t forget that Marcus Aurelius is still bumping around in that soup today even though he left earth 1,836 years ago...and we think Cal Ripken’s Ironman streak is something...”

Send your questions for the 100th episode!

Editorial Mission—Lovers Meet

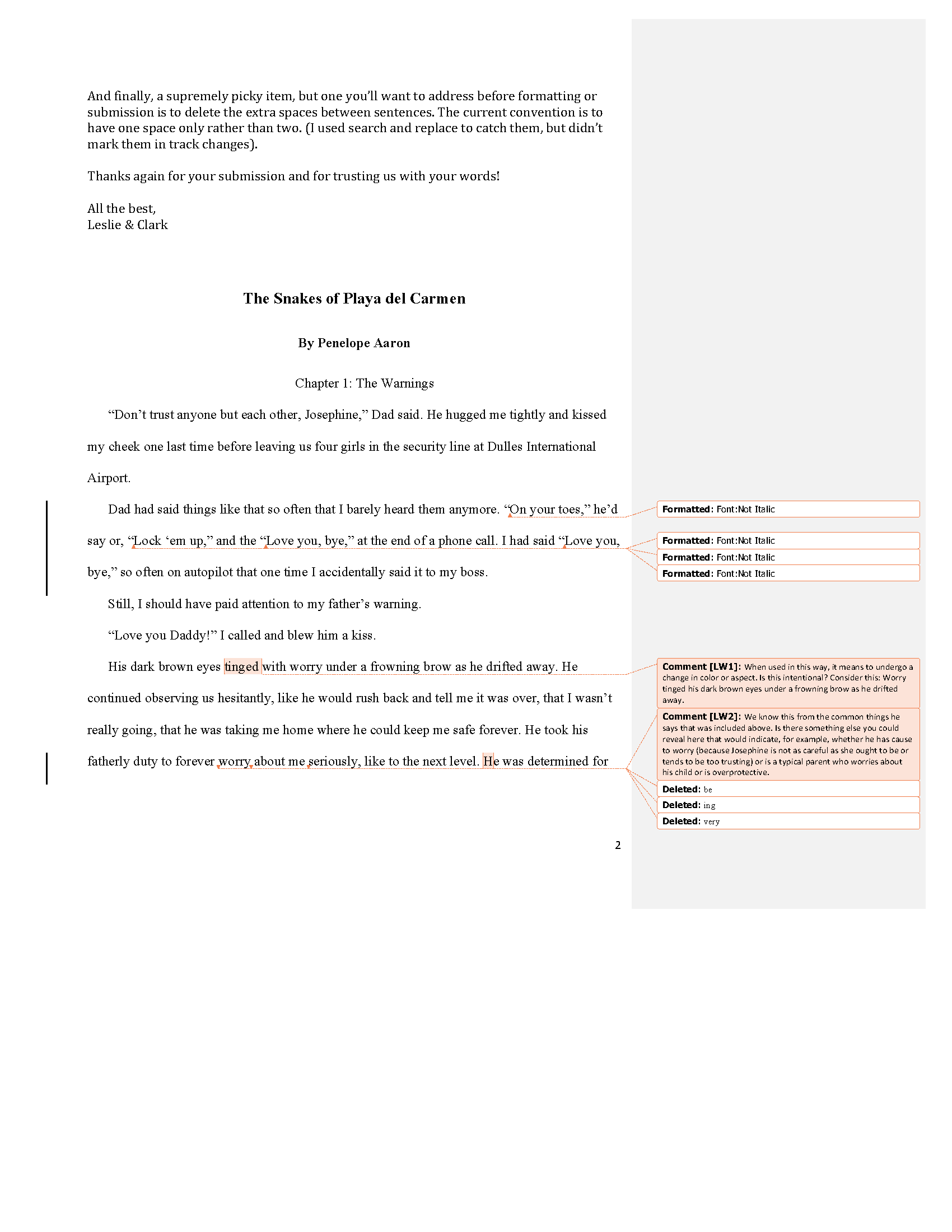

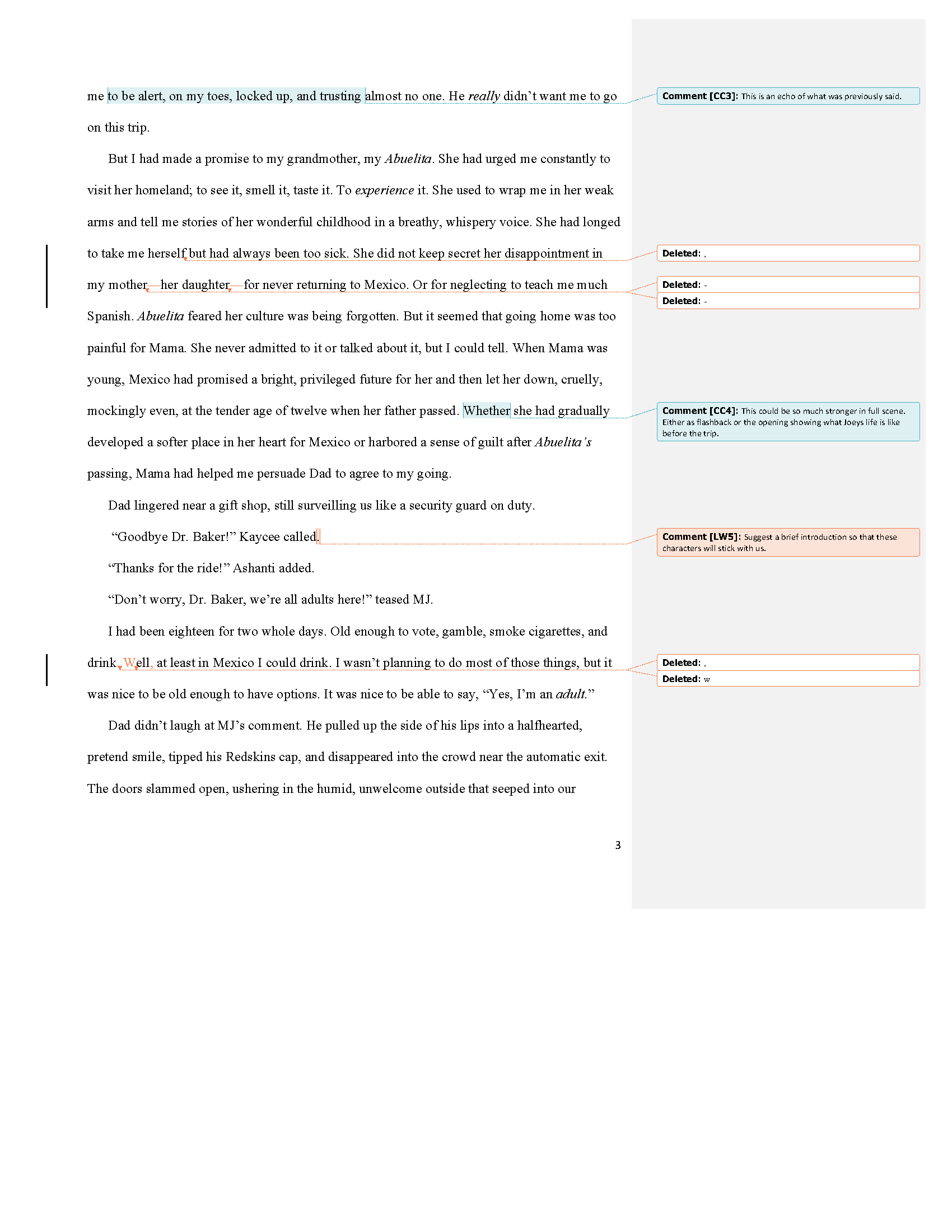

Review the scene in your story where your lovers first meet. Even if your main genre isn’t romance, you can still use the lovers meet scene to set up a love story subplot or to set up the relationship of the co-founders of a business, partners in crime, or best buddies. Write the scene where they meet even if you don’t include it in your story. It will provide insight into how the characters relate to one another.

Consider characteristic moments for both lovers (friends, colleagues); tension created by awkwardness or hostility; how to set up conflict in the relationship given their strengths, flaws, and roles they play; and how to make it memorable for both. Get stuck? Find a model to use: Pride and Prejudice is fantastic.

Do you want editorial missions sent directly to your inbox?

Sign up to join us aboard the Writership Podcast! We'll send new episodes and editorial missions directly to your inbox so you'll never miss out. You'll also get the lowdown on our top 12 writing, editing, and self-publishing podcasts—perfect if you, like us, want to live a fulfilling life as a writer.