Resolution

Special Housekeeping Note:

As a reminder, you can submit your first scene anytime before 11:59 p.m. PST on Saturday, February 3. We've changed the way you'll submit your scenes, but this should make the process easier for everyone. All you need to do is click here, answer a few questions about your submission, and upload your scene.

Our first group call is Sunday, February 4, at 1:00 p.m. PST / 3:00 p.m. CST.

Intensive Materials: Resolution

At long last, we've reached the Resolution. In this email, we'll review the Fifth (and final) Commandment of Storytelling and show you how to analyze your own scenes or those of a masterwork you want to reverse engineer.

It's easy to imagine Robert McKee,master screenwriter and the author of Story, smiling cheekily when he says the Resolution is "anything left after the climax." It's true, but thankfully he goes on to explain what that entails. The general purpose of the Resolution is to wrap things up, but we need to get more specific if we're going write effective Resolutions.

Generally speaking, the Climax will answer, not only the Crisis Question, but also the question posed by the Inciting Incident. If it's not been answered, and is not meant to be an open question, then the Resolution should clear things up. One thing the Resolution is not is a simple summation: If a character is restating what's just happened, they should illuminate the events and go deeper.

Scene Resolutions can show or demonstrate the following items regarding the characters and Story:

- The result of the life value shift;

- How the events of the scene have changed the landscape in a relevant way

- The new status quo;

- The consequences for the main character as a result of the Climactic action;

- The magnitude of the consequences, that is how the Climactic event reverberates beyond the main character to other characters and the world;

- The implications of the Climactic action, what it means for the main character and others, and why it matters;

- The characters' internal revelations, chief takeaways, or lessons learned;

- Setups for and payoffs from other scenes, as well as reminders of facts the reader needs to know; and

- Sometimes the Inciting Incident (or at least the setup for the Inciting Incident) of the next scene.

Resolutions allow the reader to do the following:

- Take stock and metabolize the action in the scene;

- Consider the contrast the character's expectations before the Climax with what actually happens;

- Release tension, and

- Feel particular emotions related to the Core Emotion of the Story.

You won't need to include each of these items in every scene Resolution, but it's good to consider the possibilities and whether you're getting the most meaning from your scene's last hurrah.

Analyzing Scenes

When we analyze a scene, we identify the Five Commandments of Storytelling, but before we look at those elements, we begin with four questions designed to get to the heart of what's happening in the scene and how it relates to the Global Story. First, we start with an easy question.

1. What are the characters literally doing in the scene?

This question is simple, straightforward, and based only on what you see. Leave out any judgments or interpretations. This should be an accurate, objective statement of what happens. Don't overthink or spend too much time dwelling on this. Record an answer and move on to the second question.

2. What is the Essential Action of what the characters are doing?

This question is from Practical Aesthetics, an acting practice developed by David Mamet and William H. Macy. Actors use it to give themselves options. They know what they are trying to get the other character to do, which gives them concrete actions they can act out.

Why are we talking about an acting concept here? Because identifying the Essence of the Character's Action will help you understand the scene better so you can revise it better. The goal is to capture the true nature of the action and the characters' intent. Consider what the characters hope to gain in the scene (What is the desire and goal that arise from the Inciting Incident?) and distill it into a pithy statement like those listed below.

- to get someone on my team

- to lay down the law

- to draw the dividing line

- to get someone to take the big risk

- to get my due/retrieve what is rightfully mine

- to get someone to see the big picture

- to enlighten someone to a higher understanding

- to tell a simple story

- to get to the bottom of something

- to close the deal

- to get someone to throw me a lifeline

The next two questions look at whether and how the scene turns and how it relates to the Global Story. If you need to refresh your memory about Life Value changes, see the post on Progressive Complications and the PDF with genres, Life Values, Core Events, and Core Emotions.

3. What life value has changed for one or more of the characters?

Like the first question above, you want to cast a wide net, but don't drive yourself crazy. Look for any change that happens in a life value for a character in the scene and record it. Consider different characters and their internal and external journeys within the scene.

4. Which life value is most relevant to the Global Story?

If you were creating a Story Grid spreadsheet of the scenes in your story, you would enter the life value shift that is most relevant to Global Story, that is the main event. Don't worry about the spreadsheet now, but that is where you would put this answer if you were analyzing your manuscript or a Masterwork and how you would see it in a Story Grid Guide or Edition.

Once you've answered the first four questions, it's time to check for the Five Commandments we've been studying.

Supplemental Materials

To find out more about Resolutions, check out this post from Shawn Coyne.

Live Scenes

We have three scenes that feature Captain Jack Aubrey and Stephen Maturin, the ship's surgeon. One important subplot involves their friendship and the way it is tested by Jack's sense of duty and the nature of living on a ship of the Royal Navy.

The Lesser of Two Weevils

In this scene, we see part of a lively dinner conversation in Jack's cabin.

Maturin Performs Surgery

In the events leading up to this scene, Captain Howard of the Royal Marines accidently shoots Maturin while the HMS Surprise is anchored near the Galapagos Islands. Surgery is required to remove the musket ball from his chest before it festers, a certain death sentence. Jack abandons his pursuit of the Acheron while Maturin is taken ashore because the movement of the ship would make the operation unsafe, so Maturin, Aubrey, the surgeon's assistant, and others go ashore. Maturin informs the others he will perform the surgery on himself with a mirror.

Acheron's Doctor Died of Fever

This scene is part of the Resolution of the Story. Jack and the crew of HMS Surprise have defeated the Acheron in battle. At the end of it, Jack receives the deceased captain's sword from the French doctor. Jack puts LT Pullings in charge of the Acheron with orders to sail for Valparaiso, parole the prisoners, and then meet in Portsmouth. Jack plans to return to the Galapagos to allow Maturin time to draw and collect unique species from the islands before setting sail for England.

Review

Identify the Resolution, what it demonstrates, and what it offers the reader in the live scenes above.

Prompt

Analyze one of the live scenes using the four questions, and then identify the Five Commandments of Storytelling within the scene.

Housekeeping: SPECIAL NOTE AND REMINDER

As a reminder, you can submit your first scene anytime before 11:59 p.m. PST on Saturday, February 3. We've changed the way you'll submit your scenes, but this should make the process easier for everyone. All you need to do is click here, answer a few questions about your submission, and upload your scene.

Our first group call is Sunday, February 4, at 1:00 p.m. PST / 3:00 p.m. CST.

If you have questions about anything, write us at hello@writership.com

Climax

Intensive Materials: Climax

In this post, we tackle the Climax, the Fourth Commandment of Storytelling, and in the Housekeeping section, you'll find the dates for our group calls and a reminder about when to submit your first scene.

If the Crisis is a question, the Climax is the answer in the form of a decision and action. These decisions and actions are character revealing because they are decisions made under pressure. As Shawn Coyne says, “the climax is the truth of the character.”

The decision and action should be apparent in the scene, but it’s often hard to separate them. The reader might need to infer the character’s decision based on the action taken. Still, it’s vital that the writer show this moment because Scene Climaxes demonstrate the change in a character over the course of the story.

Causal Connections and Setups

When you evaluate a scene, look closely at the Climax:

- Is there a clear cause and effect relationship between the Inciting Incident and Progressive Complications on the one hand and the Climax on the other?

- What facts, circumstances, and actions need to be established for the Climax to make sense and feel inevitable?

- Once you have your list of required setups, look to see that you’ve incorporated them within the scene or in an earlier one.

- Can you deliver the Climax in a way that is unexpected?

Reversibility

Some decisions in life can be reversed, but others can’t. If a decision within a scene can be easily rescinded, then there isn’t much at stake, and the reader could lose interest. It feels like cheating to put the character in a bind, force them to make a tough decision, and let them undo it right away. But there is a range of reversibility: meaning some decisions can be undone, others can be with some cost or consequences, and some cannot be undone. Consider these examples:

If you buy a pair of shoes and realize they don’t fit when you try them on at home, chances are you could return them and get the correct size. If you reveal spoilers before a friend has seen a movie and then apologize, you’ll probably be forgiven.

If the shoes are not returned in time, there may be a restocking fee or some other penalty. If you reveal a friend’s secret, the friend may need time or an act of amends before they can offer forgiveness, even if you’ve caused no actual harm.

If you’ve worn the purchased shoes outside, the store might refuse to take them back. If you reveal damaging information that causes your friend to lose their job or their romantic partner, they might not be able to forgive, even with time.

Over the course of a story, the decisions the character makes should become increasingly irreversible so that when the reader reaches the Story’s Climax, there is no question of the character’s being able to call for a do-over. Within smaller units of story (Acts and Sequences), the Climaxes should also become more irreversible from Inciting Incident to Climax as well.

Just as with the character’s initial action after the Inciting Incident, the action here creates a gap between expectation and actual result.

Supplemental Materials

To find out more about the Climax, check out this post from Shawn Coyne.

Live Scenes

Our Climax scenes include pivotal moments from Master and Commander, but they depict the harsh realities of life on a Royal Navy ship in the nineteenth century. If you find the subject matter triggering, let us know, and we'll send another scene for you to consider.

- “Men Must Be Governed.” (Trigger warning: a sailor is whipped at the end of the scene.) Here is some context for this scene: You may recall in “Man Overboard” that the HMS Surprise is caught in a violent storm as it rounds Cape Horn in pursuit of the Acheron. (See Crisis email or post.) William Warley is up in the rigging trying to secure the sails, which would catch the wind and pull the ship over if not secured. Midshipman Hollom is sent to assist Warley, but the officer is frozen with fear and fails to reach Warley in time. The mast breaks, sending Warley and the attached rigging and sails into the water. He manages to get ahold of the rigging so the men aboard can pull him in, but the rigging acts as an anchor and threatens to capsize the ship. Captain Aubrey, Sailing Master Allen, and Carpenter’s Mate Nagle must cut the rigging loose in order to save everyone aboard. As "Men Must be Governed" opens, Aubrey and Maturin are discussing an incident in which Nagle pushed past Hollom without saluting and the punishment meted out as a result.

“Hollom’s Death” is a scene that follows soon after. (Trigger warning: This scene includes a suicide.)

Review

- Identify the Climax Decisions and Actions in these scenes. Are they reversible at all? Is it likely?

- What facts, circumstances, and actions need to be established for the Climax of the scene to make sense and feel inevitable? Can you identify these items from the other scenes we’ve included in the Pre-Course Materials?

- Whether you’ve seen the entire movie or not, do you notice how the scenes we’ve shared are connected and reveal a great deal about who the characters are?

Let us know if you have any questions about this exercise. You can reach us at hello@writership.com.

Prompt

As you practice identifying the commandments in the live scenes, consider your own scenes. Can you spot the commandments easily? Are there any missing or that could be made stronger? Is there a pattern? In other words, are there commandments that are easier or better executed than others?

Housekeeping

The time for our Intensive is growing near!

As a reminder, you can send your first scene anytime before 11:59 p.m. PST on Saturday, February 3, to hello@writership.com.

Thanks so much for filling out the surveys. Here is the schedule for our calls:

- Sunday, February 4, at 1:00 p.m. PST / 3:00 p.m. CST

- Tuesday, February 6, at 4:00 p.m. PST / 6:00 p.m. CST

- Thursday, February 8, at 5:00 p.m. PST / 7:00 p.m. CST

You should have received a separate email with the time for your individual call on Saturday, February 10. If you have any questions about that, hit reply and let us know.

Crisis Question

Intensive Materials: Crisis Question

Remember from Progressive Complications email that the Turning Point Complication forces the character into a dilemma? Well that dilemma in question form is what we call the Crisis. The character has exhausted every reasonable option to achieve their goal except the two presented by the dilemma. This is the character’s last hurrah.

Two Types of Crisis Questions

The dilemma that your character encounters will come in one of two forms:

- Best Bad Choice: This is just what it sounds like—a choice between two unpleasant (or much worse) options. Taken to the end of the line, I think of Sophie’s Choice, a story in which a woman must decide which of her children will live. How could a person make that choice? That’s one of the reasons we go to story: We face difficult decisions in our lives, though thankfully for most of us it’s nowhere near that heartbreaking, and we want lessons for life about how to choose.

Irreconcilable Good Choice: This can present as two good options when the character can’t choose both, OR a choice that’s good for the character, but bad for someone else. For example, in Pride and Prejudice, Darcy faces an irreconcilable goods crisis about whether to intervene on Lydia’s behalf after she runs away, unmarried, with Wickham. If he avoids the situation, his reputation and status remain intact, and that’s good for him. If he saves Lydia from her mistake, he helps Elizabeth and the other Bennet girls.

These choices can be a bit "squishy" as Shawn Coyne says. Sometimes it’s a matter of perspective and whether the character sees a glass as half-full or half-empty. We could frame Darcy’s choice as being a Best Bad Choice, but that label won’t change the critical significance of the decision he faces: He can’t have it both ways, and it’s a difficult decision to make. A simple choice between good and evil isn’t a real dilemma.

Make It Specific

How the character responds in these critical moments tells us a great deal about who they are, and making the dilemma specific to them will make for more compelling stories and scenes.

Specificity comes from in part from knowing what’s at stake. For example, consider the dilemma of a whistleblower in a cigarette company during the 1970s or 1980s. They risked losing their jobs as well as the possibility for future employment. If a character is single, independently wealthy, and skills marketable outside the industry, then the character wouldn’t necessarily agonize over the decision to speak up about the harmful nature of cigarettes. Give that character a family, mortgage, and no other skills, then it becomes a more difficult choice.

Stakes are not only about how what the actual risks are, but what it means for the character. For some people, death or the death of a loved one is the worst thing that could happen. For others, it might be moral disgrace or failure. If you understand and convey what’s on the line and how the character feels about it, you’ll write more powerful scenes.

By being specific about the character’s dilemma, you create a situation that anyone can relate to. So, think about your own dilemmas in life, the times when you faced best bad choices or choices between irreconcilable goods. This is the essence of writing “what you know.” Tap into your experience of facing these kinds of decisions let that inspire your writing.

Dramatically Obvious

As Robert McKee says, the dilemma should be “dramatically” obvious. This doesn’t mean the dilemma needs to be explicit, though sometimes it is. It rarely is in films or in written stories where we don’t have access to the character’s thoughts. But the context or subtext should make it clear that the character has to decide between two main options, and that it’s difficult. Sometimes a character will serve as a herald and say it out loud. In our Master and Commander scenes, the sailing master, John Allen (played by Robert Pugh), often fulfills this role.

Scene to Story

While we focus on scenes for the Intensive, we want to remind you that scenes are connected to the Global Story. The dilemma within a scene should, of course, impact a character’s scene goal (the one that arises from the Inciting Incident), but it should also be related to the Global Story Objects of Desire or their Needs and Wants. This means that whatever the character decides should bring them closer to or further from that goal.

Supplemental Materials

- To find out more about Crisis Questions, check out this post from Shawn Coyne.

In this post, Shawn talkes about Best Bad Choices.

In this post, Shawn explains Irreconcilable Goods Choices

Live Scene

In this scene, the crew of HMS Surprise is in a terrible storm, and popular crew member William Warley (the one who gave crucial information to Captain Aubrey about the Acheron in the clip labeled “Phantom”) has been washed overboard. (Excerpt from the screenplay.)

What do you think the Crisis is in this scene? (Hint: look for the Turning Point that forces the dilemma)

How would you frame this Crisis? Best Bad Choice or Irreconcilble Goods? Why?

What seems to be at stake for the character?

We’d love to hear your thought process on this one. You can reach us at hello@writership.com.

Prompt

Set a timer for five or ten minutes and write about a time when you faced a difficult decision. How did you make the decision? What did you consider?

Housekeeping

We’ve got more posts coming before Saturday night, but before it's time to submit, we want to take a moment to explain exactly how the Intensive will work.

As a reminder, you can submit your first scene anytime before 11:59 p.m. PST on Saturday, February 3. We've changed the way you'll submit your scenes, but this should make the process easier for everyone. All you need to do is click here, answer a few questions about your submission, and upload your scene.

Our first group call is Sunday, February 4, at 1:00 p.m. PST / 3:00 p.m. CST.

- Your submission can be a scene from a work in progress or a scene you've written just for the Intensive.

- The ideal length for scenes in this Intensive is 1,500–1,800 words. Please let us know if that will be a challenge.

- Word Docs or Pages files are easiest for submission, but let us know if you need to use a different format.

- We'll upload the scene to Google Docs and share the link with you along with our written feedback and suggestions by noon PST the following day. This will allow us to respond to comments and questions right in the document.

- You'll revise the scene (either in the Google Doc or in your own document) and resubmit via email by midnight PST. (We'll save the different versions in a file we'll share with you, so that you can review your progress.

- We strongly recommend that you submit your scenes for at least two rounds of feedback. You can submit between two and four different scenes during the week.

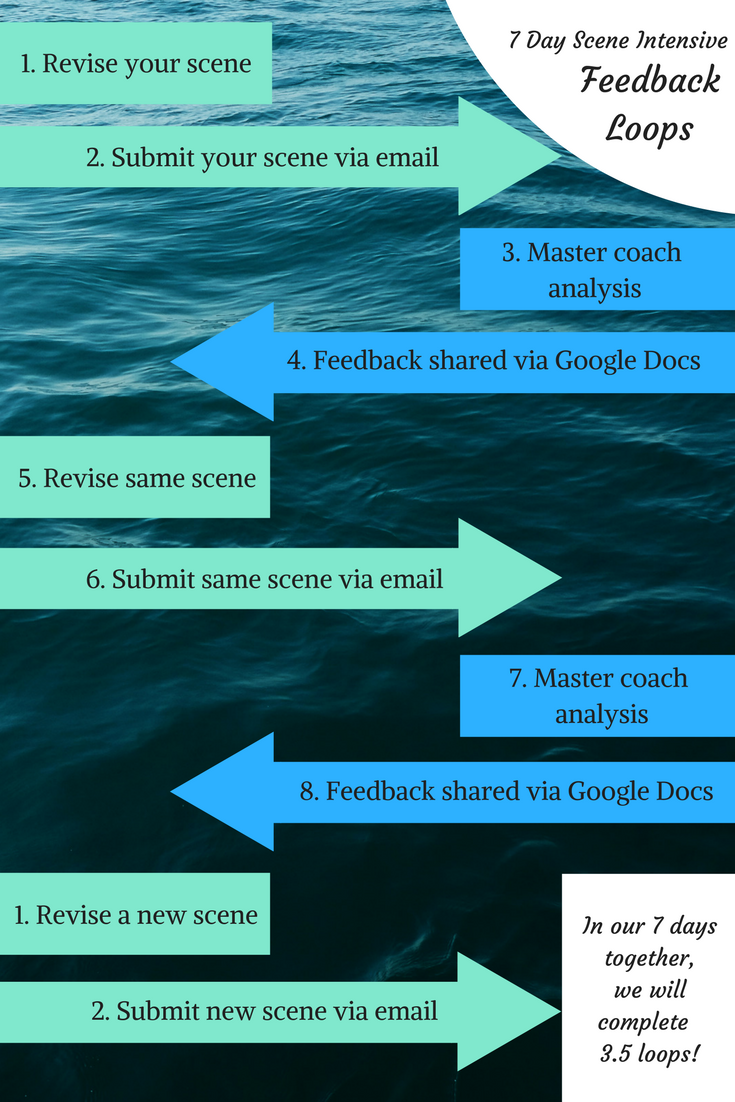

Here’s a visual representation of how this will work.

Group and Individual Calls

In case you missed it, here is a survey to help us pick the best time for our upcoming calls. Please take a moment to fill it out and let us know your preferences for meeting times.

Any questions? Write us at hello@writership.com.

Progressive Complications

Intensive week is going to be here before you know it. And we can’t wait! We are so looking forward to meeting and working with you. Today things get complicated—progressively complicated, that is as we tackle Commandment Number 2. This is a particularly dense email, and we want to get this off to you, so we'll send the live scenes in another email later today.

Intensive Materials: Progressive Complications

Do you remember the scene goal that comes from the character’s desire to restore balance after an inciting incident, which we mentioned in email #2? If so, then you're already ahead because Progressive Complications are the obstacles the character faces in pursuit of that goal. When the character takes action, they find themselves thwarted by other characters, the environment, or circumstances.

The character should face multiple Progressive Complications within a scene, sequence, act, and story, and we call them “progressive” because the obstacles grow increasingly more difficult and make it more unlikely that the character will reach their goal. If the obstacles stay the same or become easier, the reader can lose interest quickly.Another way to lose the reader's intersest is to repeat the same complications without making them bigger or increasing what's at stake for the character.

There are two Progressive Complications you’ll want to be particularly mindful of, no matter which unit of story you’re dealing with: the last Complication before the Turning Point and the Turning Point itself.

The Progressive Complication we record in our scene analysis is the one that comes just before the scene turns or life value changes in a meaningful way. This is the character’s last chance to make a particular strategy work before they’re forced to make a change or risk failure.

The Turning Point forces the character into a dilemma the character must react to and is tracked in the Story Grid spreadsheet. This is one of the first clues that will tell you if your scene is working or not.

Let’s get clear about what we mean by turning the scene? In essence, the Turning Point is a gap between what the character expects to have happen and what actually happens.

Stories are about change, and there are micro changes that happen within your scenes that add up to the macro change that happens over the course of the story. The nature of the change that happens isn’t random, though. It’s related to the human need implicated by the genre, and we call that the Life Value at Stake. We don’t want to get too macro during our Scene Intensive, but keep in mind that the way a scene turns should impact the way the entire story turns.

(You can find a PDF with the genres, life values, and human needs here.)

What is a Life Value?

So, a life value describes a change from one state to another caused by an event orexperience.

Here's a simple example: Before it rains (event), the grass outside is dry (state). After it rains, the grass is wet. That's a change in the state of the environment that flows from a natural event. The same event could potentially affect a value for a character and might represent success or hope if, for example, the property in question is a farm in a region suffering a prolonged drought.

Here's an example of a change directly related to a character's state: Before eating (event), a person is hungry (state), and after eating, she is full. That's a change in her physiological state. If she had been deprived of food for two weeks, this event could cause her state to shift from possible death to life.

Here's an example of a value shift in the context of a story scene. Before a man meets a potential love interest (event and experience), he might feel alone (state), and after the two connect, they are together (at least temporarily) and he might feel companionship. The same scene might be characterized as a change from ignorance (if the two don't know of each other) to attraction (if they like each other). Over the course of an entire courtship love story (like Pride and Prejudice), a couple might move from ignorance all the way to commitment.

There will be changes that are different from the Global Story/Core Value (see the PDF mentioned above for more info about that.. For example, in a crime story, the discovery of the body scene will move from Life to Death, but the Global Value in a Crime Story is Justice to Injustice. They are related, but you can see how they are different. For a full Story Grid spreadsheet with an eye toward tracking the external and internal subplots as well as the subplots, you can might make note of several. For the Story Grid Edition of Pride and Prejudice, Shawn tracked the love story (external) and maturation plots (internal) for Elizabeth Bennet as the protagonist) as well as the external subplots for the love story between Jane Bennet and Bingley and Lydia Bennet and Wickham.

Two types of Turning Points

- Character Action: A character does something that changes circumstances materially.

- Revelation: Information is revealed that chages circumstances materially.

If you’ve ever heard someone recommend using exposition as ammunition, what they mean is to save backstory and other information for when it can used as a revelatory turning point, through conflict, so that it forces a dilemma.

We track the turning point as well as it's type across the entire story to be sure that we’re not using the same type too often. In fact, if you think the reader is expecting one, consider using the other.

Turning Points Affect the Reader

Turning points that are well executed cause the reader to stay engaged with the story and experience their own emotional cycles.

- The reader feels surprise because there is a gap between the character’s expectation and what actually happens.

- The reader becomes curious about why the gap occurred.

- The reader reviews information they already know about the characters and events of the story.

- The reader gains new insight and and a deeper understanding of what has come before.

For example, in The Empire Strikes Back, there is a revelatory turning point when Darth Vader tells Luke Skywalker who his father is. George Lucas had begun setting that moment up in the beginning of the prior movie. The revelation

Supplemental Materials

- Check out Leslie’s post on why scenes need conflict

- Read Shawn Coyne's post on Commandment Number 2: Progressive Complications.

- Then read the post on the Little Buddy of Commandment Number 2 - The Turning Point.

Live Scenes

Here are two scenes from Master and Commander to help you get a feel for Progressive Complications. (Keep in mind that the screenplay can vary from the final cut of the film.)

Consider how the events within the scene progressively complicate the POV character's attempt to reach their scene goal. Can you identify the Progressive Complication that comes before the turning point and the one that turns the scene? Does the scene turn on Action or Revelation?

Housekeeping

One of the great things about the 7 Day Scene Intensive is that it’s remote, so no one has to travel or leave their families. Even so, it’s essential that we connect, so we'll hold Skype calls during our intensive week. The first one will be a group call Sunday, Feb 4, at 1:00 pm PST/3:00 pm CST.

We'll also hold group calls on Tuesday, Feb 6, and Thursday, Feb 8. We encourage you to attend because these meetings are great opportunities to ask questions, get clarification on the materials, and discuss challenges and successes. The Intensive will wrap up on Saturday, Feb 10, with individual coaching calls.

Please take a moment to respond to this survey, and we'll choose the best time for our meetings.

Question

Can you think of moments in stories you've read or in your own life when obstacles seemed to grow worse and then force you into a dilemma?

Inciting Incidents

Intensive Materials: Inciting Incident

Today we look at the first Commandment of Storytelling: the inciting incident. This is an event that upsets the balance in life or the status quo and is a catalyst for everything that follows within the scene or other unit of story.

To get a clear sense of this, consider the basic story structure former Pixar story artist Emma Coats, has shared.

Within the bones of this fill-in-the-blank story, the sentences that start “Once upon a time” and “Every day” describe the status quo. “One day” is the inciting incident when things begin to change.

You can also think about the inciting incident as the call to adventure within the hero’s journey. The purpose is to kick things off.

What are the elements of an inciting incident?

The inciting incident upsets the status quo, but it must do more than that. If the event happens and the protagonist or POV character shrugs his shoulders, the story or scene won’t go anywhere. The event must cause the character(s) to react. We can see the inciting incident as four different elements:

- The event throws the character or their life out of balance.

- The desire to reset the balance arises within the character.

- This desire becomes a goal the character believes will reset the balance. The goal could be an attitude or belief, the acquisition of some object, or a change in circumstances.

- The character takes action in pursuit of the goal.

These elements won’t always be explicit, but the reader should be able to see them within the subtext of the story.

What are the qualities of an inciting incident?

Inciting incidents can be

- positive (a character receives a financial windfall or a teacher encourages students to seize the day) or

- negative (a man is shot and killed in the middle of town or an enemy ship fires on a frigate)

- causal or an active choice (a character sets out on a journey or decides to leave their spouse) or

- coincidental (a shark attacks swimmers or two men of great fortune move into the neighborhood)

Supplemental Materials

Check out this article from The Story Grid site about Inciting Incidents:Commandment Number One.

Live Scenes

Watch this scene from Master and Commander and identify the inciting incident. Are the four elements apparent from the context even though they're compressed and implied. (You can find an excerpt from the screenplay for this scene here.)

UPDATE: Was it a false alarm, or was there indeed an enemy ship lurking in the fog? Find out here. (The excerpt from the screnplay can be found here.)

Housekeeping

It’s not too early to be thinking about which scenes you want to work on during the intensive. Your first scene submission is due Saturday, February 3, 2018, at 11:59 p.m. Pacific time. Don’t worry, we’ll remind you again before then. In the meantime, and as you work through the pre-course materials, think about how these topics might apply to the scenes you want to submit. Remember, you’re free to write fresh scenes if you want, but you can also use scenes from a work in progress.

Prompt

Think about a story you’ve read or watched lately. What event kicked things off? Can you identify the four elements?

In the context of your own life, consider the inciting incidents you’ve experienced. Look at small and large events, causal and coincidental, positive and negative. How did you feel when you were in the middle of the event and afterward? Remember that you can use your reactions and emotions to inform what your characters say and do in similar circumstances.

Welcome to the 7 Day Scene Intensive Pre-Course

Welcome to the 7 Day Scene Intensive Pre-Course. I’ve prepared some great content for you to take in before you submit scenes by midnight Pacific time on May 26. We don’t want you to miss any information related to the Intensive, so please take a moment to whitelist hello@writership.com by adding it to your contacts.

Submissions

To submit your scenes for the Intensive, all you need to do is click here, answer a few questions about your submission, and upload your scene. We'll include this link in every email, so it will be handy when you need it.

About the Pre-Course Materials

Our intention with the pre-course materials is to help you become familiar with the structure and components of scenes in advance. We want to provide a foundation that you can absorb at your own pace so you can make the most of our time during the Intensive. The information has been divided into manageable installments because it’s a lot to take in and we know you have other demands on your time. We recommend marking time in your calendar so this important step isn’t neglected.

- Intensive Materials include information and explanations to help you understand what goes into a scene that works.

- Supplemental Materials include articles from the Story Grid site and other sources for additional support.

- Live Scenes are movie clips and screenplay excerpts to help you identify the Five Commandments and other components of scenes.

- Housekeeping information so you’ll know what to expect every step of the way, including the schedule for submissions and calls and instructions for uploading your scenes.

- Question or Prompt to help you think about the work in different ways.

For our first installment, we'll begin with some basics.

Intensive Materials: What is a scene?

Before we start studying scenes in earnest, we should start with a solid working definition. Scenes are the smallest complete unit of story and the building blocks of stories. Robert McKee says a scene is “an action through conflict in a unity or continuity of time and space that turns the value-charged condition of the character’s life.”

If we add some flesh to those bones, we might say a scene is a unit of story in which

a character takes action toward a goal that arises from an immediate problem or opportunity, and

the character encounters troublesome obstacles until

circumstances change, and the character faces a dilemma,

makes a decision, and acts on it,

from which consequences follow.

You can see how these components create a mini-story with loads of possibilities. In our next email, we'll look at Inciting Incidents, the event that kicks off a story or scene.

Supplemental Materials: The Five Commandments of Storytelling

Take a few minutes to read this article from the Story Grid site that introduces you to the Five Commandments of Storytelling.

Live Scenes: Master and Commander

We’ll be using a favorite movie of mine during our pre-course studies: the 2003 film Master and Commander (screenplay by Peter Weir and John Collee). Watch the trailer here to get a feel for the story and pay attention to the emotions evoked as you watch.

Housekeeping

You've already found our home base for the 7 Day Scene Intensive, and if you haven't already, take a moment now to bookmark the page. I'll post important notices here, as well as information and resources from the Pre-Course materials. If you need anything or have questions related to the 7 Day Scene Intensive, you can reach me at hello@writership.com.

Question

It’s so useful to be clear about our intentions when we embark on a new journey. Take a few minutes to consider and record what you hope to gain from our time together. If you’d like, hit reply and share your intention.

If you have questions at any time during the Intensive, simply reply to one of these emails, and we’ll get back to you as soon as we can.

All the best,

Leslie & Kim

p.s. Remember to whitelist hello@writership.com by adding it to your contacts, so you don’t miss a thing!