Intensive Materials: Crisis Question

Remember from Progressive Complications email that the Turning Point Complication forces the character into a dilemma? Well that dilemma in question form is what we call the Crisis. The character has exhausted every reasonable option to achieve their goal except the two presented by the dilemma. This is the character’s last hurrah.

Two Types of Crisis Questions

The dilemma that your character encounters will come in one of two forms:

- Best Bad Choice: This is just what it sounds like—a choice between two unpleasant (or much worse) options. Taken to the end of the line, I think of Sophie’s Choice, a story in which a woman must decide which of her children will live. How could a person make that choice? That’s one of the reasons we go to story: We face difficult decisions in our lives, though thankfully for most of us it’s nowhere near that heartbreaking, and we want lessons for life about how to choose.

Irreconcilable Good Choice: This can present as two good options when the character can’t choose both, OR a choice that’s good for the character, but bad for someone else. For example, in Pride and Prejudice, Darcy faces an irreconcilable goods crisis about whether to intervene on Lydia’s behalf after she runs away, unmarried, with Wickham. If he avoids the situation, his reputation and status remain intact, and that’s good for him. If he saves Lydia from her mistake, he helps Elizabeth and the other Bennet girls.

These choices can be a bit "squishy" as Shawn Coyne says. Sometimes it’s a matter of perspective and whether the character sees a glass as half-full or half-empty. We could frame Darcy’s choice as being a Best Bad Choice, but that label won’t change the critical significance of the decision he faces: He can’t have it both ways, and it’s a difficult decision to make. A simple choice between good and evil isn’t a real dilemma.

Make It Specific

How the character responds in these critical moments tells us a great deal about who they are, and making the dilemma specific to them will make for more compelling stories and scenes.

Specificity comes from in part from knowing what’s at stake. For example, consider the dilemma of a whistleblower in a cigarette company during the 1970s or 1980s. They risked losing their jobs as well as the possibility for future employment. If a character is single, independently wealthy, and skills marketable outside the industry, then the character wouldn’t necessarily agonize over the decision to speak up about the harmful nature of cigarettes. Give that character a family, mortgage, and no other skills, then it becomes a more difficult choice.

Stakes are not only about how what the actual risks are, but what it means for the character. For some people, death or the death of a loved one is the worst thing that could happen. For others, it might be moral disgrace or failure. If you understand and convey what’s on the line and how the character feels about it, you’ll write more powerful scenes.

By being specific about the character’s dilemma, you create a situation that anyone can relate to. So, think about your own dilemmas in life, the times when you faced best bad choices or choices between irreconcilable goods. This is the essence of writing “what you know.” Tap into your experience of facing these kinds of decisions let that inspire your writing.

Dramatically Obvious

As Robert McKee says, the dilemma should be “dramatically” obvious. This doesn’t mean the dilemma needs to be explicit, though sometimes it is. It rarely is in films or in written stories where we don’t have access to the character’s thoughts. But the context or subtext should make it clear that the character has to decide between two main options, and that it’s difficult. Sometimes a character will serve as a herald and say it out loud. In our Master and Commander scenes, the sailing master, John Allen (played by Robert Pugh), often fulfills this role.

Scene to Story

While we focus on scenes for the Intensive, we want to remind you that scenes are connected to the Global Story. The dilemma within a scene should, of course, impact a character’s scene goal (the one that arises from the Inciting Incident), but it should also be related to the Global Story Objects of Desire or their Needs and Wants. This means that whatever the character decides should bring them closer to or further from that goal.

Supplemental Materials

- To find out more about Crisis Questions, check out this post from Shawn Coyne.

In this post, Shawn talkes about Best Bad Choices.

In this post, Shawn explains Irreconcilable Goods Choices

Live Scene

In this scene, the crew of HMS Surprise is in a terrible storm, and popular crew member William Warley (the one who gave crucial information to Captain Aubrey about the Acheron in the clip labeled “Phantom”) has been washed overboard. (Excerpt from the screenplay.)

What do you think the Crisis is in this scene? (Hint: look for the Turning Point that forces the dilemma)

How would you frame this Crisis? Best Bad Choice or Irreconcilble Goods? Why?

What seems to be at stake for the character?

We’d love to hear your thought process on this one. You can reach us at hello@writership.com.

Prompt

Set a timer for five or ten minutes and write about a time when you faced a difficult decision. How did you make the decision? What did you consider?

Housekeeping

We’ve got more posts coming before Saturday night, but before it's time to submit, we want to take a moment to explain exactly how the Intensive will work.

As a reminder, you can submit your first scene anytime before 11:59 p.m. PST on Saturday, February 3. We've changed the way you'll submit your scenes, but this should make the process easier for everyone. All you need to do is click here, answer a few questions about your submission, and upload your scene.

Our first group call is Sunday, February 4, at 1:00 p.m. PST / 3:00 p.m. CST.

- Your submission can be a scene from a work in progress or a scene you've written just for the Intensive.

- The ideal length for scenes in this Intensive is 1,500–1,800 words. Please let us know if that will be a challenge.

- Word Docs or Pages files are easiest for submission, but let us know if you need to use a different format.

- We'll upload the scene to Google Docs and share the link with you along with our written feedback and suggestions by noon PST the following day. This will allow us to respond to comments and questions right in the document.

- You'll revise the scene (either in the Google Doc or in your own document) and resubmit via email by midnight PST. (We'll save the different versions in a file we'll share with you, so that you can review your progress.

- We strongly recommend that you submit your scenes for at least two rounds of feedback. You can submit between two and four different scenes during the week.

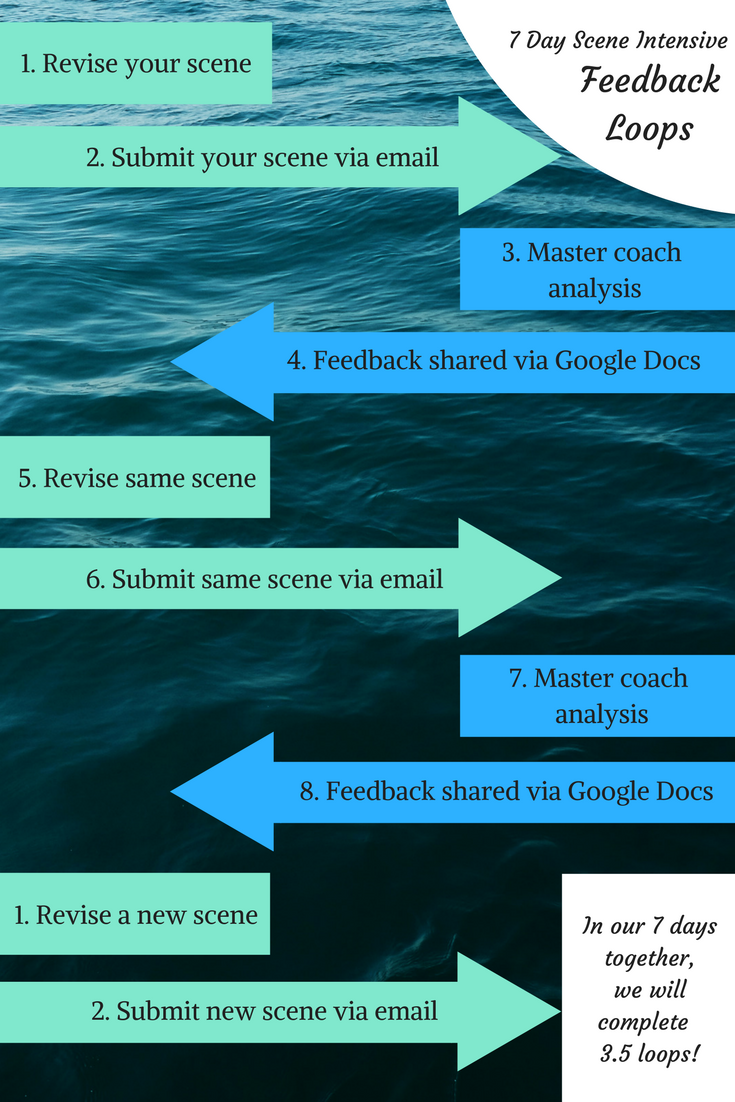

Here’s a visual representation of how this will work.

Group and Individual Calls

In case you missed it, here is a survey to help us pick the best time for our upcoming calls. Please take a moment to fill it out and let us know your preferences for meeting times.

Any questions? Write us at hello@writership.com.