Fiction editor Leslie Watts is joined by Liz Green, Writership’s first officer, to discuss the first chapter of The Left-Handed Gunslinger, a western fantasy novella by Shaun Gill. In this episode, they explore intentional sentence structure.

You have a wide variety of tools to support your story, including the words and sentence structure you choose. The trick is to understand when to use different tools to provide the reading experience you’re aiming for.

This week’s editorial mission will help you get granular so you can revise your sentences with intention.

Special note: Clark Chamberlain is taking a well-deserved break from the podcast, so we’ll invite guest hosts for the next couple of months.

Listen to the Writership Podcast

About Our Guest Host

Clark Chamberlain is taking a well-deserved break from the podcast, so this week Leslie is joined by Liz Green. Liz is the first officer of the Writership Crew and the ghostwriter behind Green Goose Ghostwriting. She helps entrepreneurs write books that build their businesses.

A Post Graduate Degree in Journalism and a decade of working in news, PR, marketing and events taught Liz to find the nuggets in other people's knowledge and turn them into transformative stories. Through years of ghostwriting blogs she learned to listen and look deep, and to emulate bloggers' voices. As she started working with authors and editors, she found joy in helping them express their ideas and experience in a way that truly felt "like them."

Now she works with entrepreneurs who want to turn their ideas and experience into a book that builds their business.

Wise Words on Intentional Sentence Construction

“It is important to express actions as verbs, but the first principle of a clear style is this: Make the subjects of most of your verbs the main characters in your story.”

“Whether you write short, punchy sentences or long, flowing ones, keeping track of your subjects and predicates can prevent your prose from shifting and drifting.”

Mentioned on the Show

Listeners have asked for an index of the podcast episodes and the topics discussed, so we've put together a Google spreadsheet containing details of each episode, its airdate, author name, story title, genre, story type, published location, author website, and topics discussed. Get access to the spreadsheet here.

Leslie attended the Story Grid Editor Certification Training last week in Nashville. You'll hear more about this on the blog soon but in the meantime, visit Shawn Coyne's website to find out more about the Story Grid.

Episode 101 is the one in which we talked about narrative distance.

To find out more about using Microsoft Word macros in editing, check out this post by Jordan McCollom.

We want to give a shout out to our new Patreon supporter, Colby Rice. Colby is the author of The Ghosts of Koa series, which appeared in an earlier episode of the podcast.

Editorial Mission—Intentional Sentence Construction

No matter where you are in your work-in-progress, whether you have a raw first draft or something that’s ready to go to press, select a five-page sample to analyze, preferably a passage you haven’t reviewed recently. If time is tight, try two pages. Copy and paste that sample in a new document.

Read the entire sample quickly.

Read the sample sentence by sentence and mark the subject and predicate for each. (Reminder: The subject of the sentence is the person, place, thing, or idea that is doing or being in the sentence. The predicate expresses the doing or being.) If you do this on a hard copy, you could circle the subject and put a square around the predicate. If you’re reviewing a digital copy, you can use bold and underline or different colors to highlight them. Save this as a new document.

Review your subjects and predicates and ask yourself, is the subject the main character or actor in the sentence? Is the predicate an expression of the main action in the sentence? If you answer no to either of those questions, do you have specific and compelling reason to de-emphasize the main character or action? If not, rewrite the sentence. (What constitutes a specific and compelling reason? You don’t want to reveal the actor to the reader [mistakes were made], the POV character doesn’t know or can’t perceive who the actor is [I was shoved from behind], or the actor is irrelevant [the cake was ruined]).

Set the revised sample aside for a day or two then read it again. How does it sound? Is there anything you would tweak or change to make it stronger?

If you had to change several sentences, it could feel overwhelming. Don’t be discouraged! Try this as a practice four to seven times. Once you know the problem is there and you train your mind to spot it, you won’t have to go through the process of marking each sentence. I do recommend doing the test for each new manuscript, though. I mentioned that you can try this no matter where you are in the writing process, but typically you won’t be tackling sentence-level edits until the copyediting phase. Make your story-level edits first before getting down to this level.

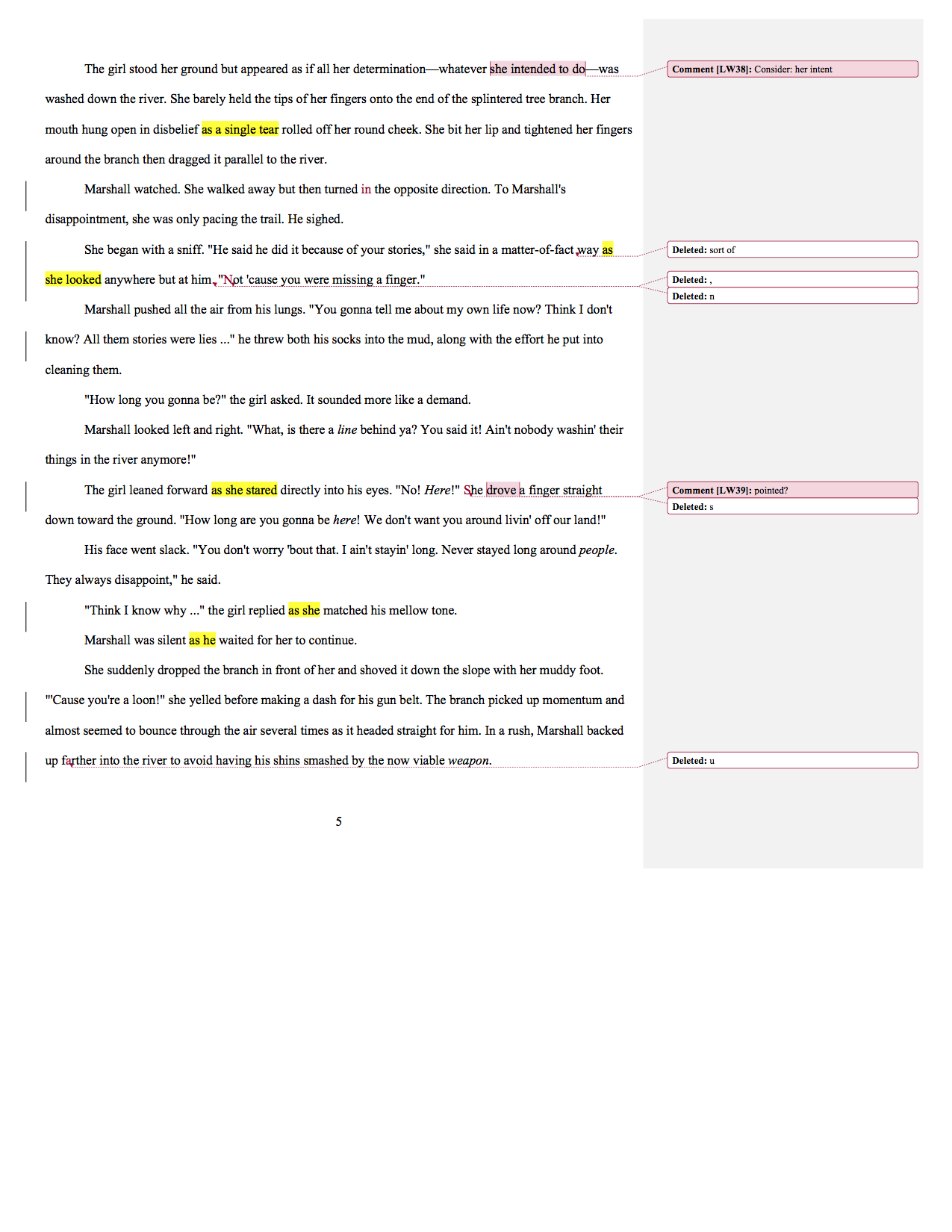

Editing Advice to Our Author

Dear Shaun,

Thank you so much for sharing your story world with us! As I mentioned in the episode, I think the combination of western and fantasy is fun one. You’ve got some great lines in these passages and mysteries that make us want to read on (Why was Marshall telling stories, and what were they about?). Leaving out the four-letter word at the end of chapter 1 was a great choice. It’s much funnier written that way. I like the way you revealed what Marshall looks like (e.g., handlebar mustache) through action instead of providing a police description for him.

One area I would focus on—but not until you’re doing sentence level edits—is passive construction. Passive writing includes the passive voice and making inanimate objects the actor in sentences. There are a few problems that arise with when we repeat this sentence construction. It takes away from the action in the scene (the character is passive, and the objects around him/her are doing and being). Passive writing can make the sentences wordy, awkward, and also alter the narrative distance in tight/limited 3rd person POV, where the character provides the lens through which we experience the story. Perhaps most important, as readers, we care about and bond with the character, not the objects in the scene, and when we make the characters the subjects of our sentences, we relate to the character and can imagine the action more easily.

Of course, this is not a blanket prohibition on passive construction. There are instances when it can be useful. For example, if you want to vary the sentence structure and emphasize something besides the character. Also, you may want to use it as a subtext to show that the character is acting passively. The passive voice comes in handy when you don’t want to say who the actor is (mistakes were made), the POV character doesn’t know or can’t perceive who the actor is (I was shoved from behind), or the actor is irrelevant (the cake was ruined).

Active writing and voice are generally more engaging, so you’ll want to be intentional about your choices and use the alternatives sparingly.

If you apply the editorial mission I mention in the episode to this piece, you might add the mission from episode 71 to get some specific and descriptive verbs doing the heavy lifting for you.

There are some echoes that you’ll want to flag for later revision stages. “Character doing something as s/he does something else” is a common structure in these pages. The good news is you know it’s there, so you can spot it. The better news is that as you rework sentences to avoid it in revision, you’ll use it less and less often in the early drafts of your work.

One story level item that I want to mention is the fantasy element. You mentioned that it comes along later, and I’m not sure if that means as soon as chapter 2 or much later. Typically, to satisfy reader expectations and orient your reader to the story you want to tell, it’s best to give them the level of reality up front. I would recommend checking this out so that it doesn’t feel like a cheat or deus ex machina to the reader.

Thanks again for sharing the opening of The Left-Handed Gunslinger with us!

All the best,

Leslie

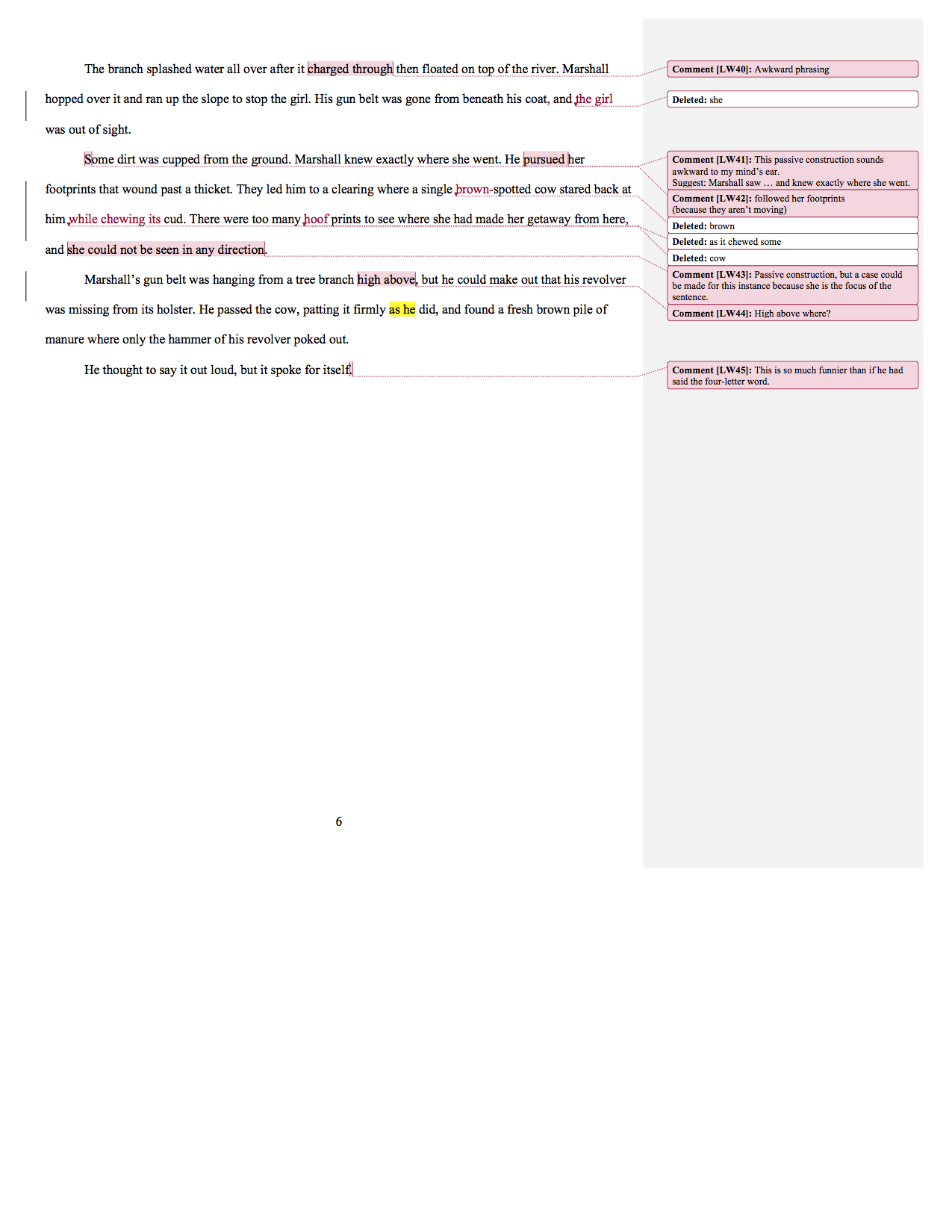

Line Edits for Our Western Fantasy Story

Image courtesy of GeraKTV/bigstockphoto.com.