In this episode, I'm joined by best-selling author and fiction editor Valerie Francis while Clark is away. We critique the prologue of Shadow Falls, a thriller novel by Maxwell Perkins. Scenes are the building blocks of your story, but how do you know if an individual scene works? Valerie and I use Shawn Coyne's Story Grid analysis to look at what's working in this opening scene and how the author might make it stronger.

We have a special treat for you. The author is a professional audiobook narrator, and agreed to share a reading of his submission with us. We weren't able to include it in the podcast episode that aired, but we've included it here in the show notes. We're considering having professional narrators read the submissions in future episodes. If you have a moment, please let us know in the comments or at hello@writership.com if this sounds like a good addition to the podcast.

Listen to the Writership Podcast

Wise Words on scenes

“There is just no hiding for a writer when it comes to a scene. It either works or it doesn’t. There is either a very clear shift in value from beginning to end—a change—or there isn’t. If there is no change, no value at stake, no movement, the scene doesn’t work. And if the writer’s scene doesn’t work, no matter how well he can craft a sentence, his Story won’t work.

”

Mentioned in the Episode

You can find the video about Ian Rankin's writing process here.

You can find Shawn Coyne's original post on the Five Commandments of Storytelling here, and this is an episode of the Story Grid Podcast in which he takes a deeper dive into these topics.

Want to learn more about Valerie? You can find her here.

Editorial Mission—Check Your Scenes

Review a scene in your story to discover whether it's working, and why or why not, by unpacking the six elements of a successful scene (You can see our analysis of the submission in the letter to the author below):

- Inciting incident: an action or coincidence that throws the main character in the scene off balance

- Progressive complications: the obstacles that get in the way of your main character's scene goal

- Turning point: an action or revelation that brings the main character to a point of no return

- Crisis question: having reached a point of no return, the character faces a choice of the best or two bad choices or two irreconcilable good choices

- Climax: the main character's choice

- Resolution: what happens as a result.

If you find something that’s missing or that could be made stronger, add it to your list of items you need to fix (rather than trying to fix it right away).

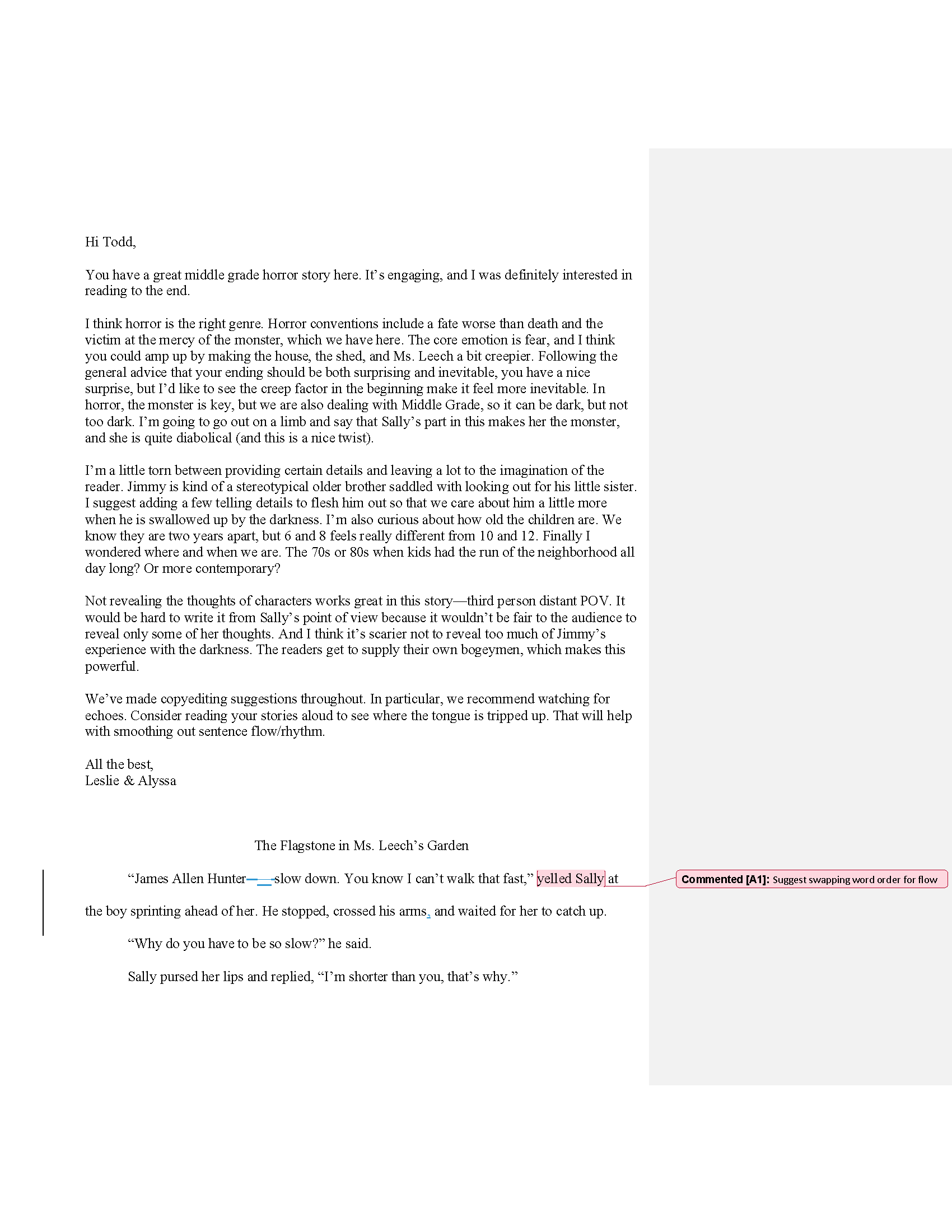

Editing Advice to Our Author

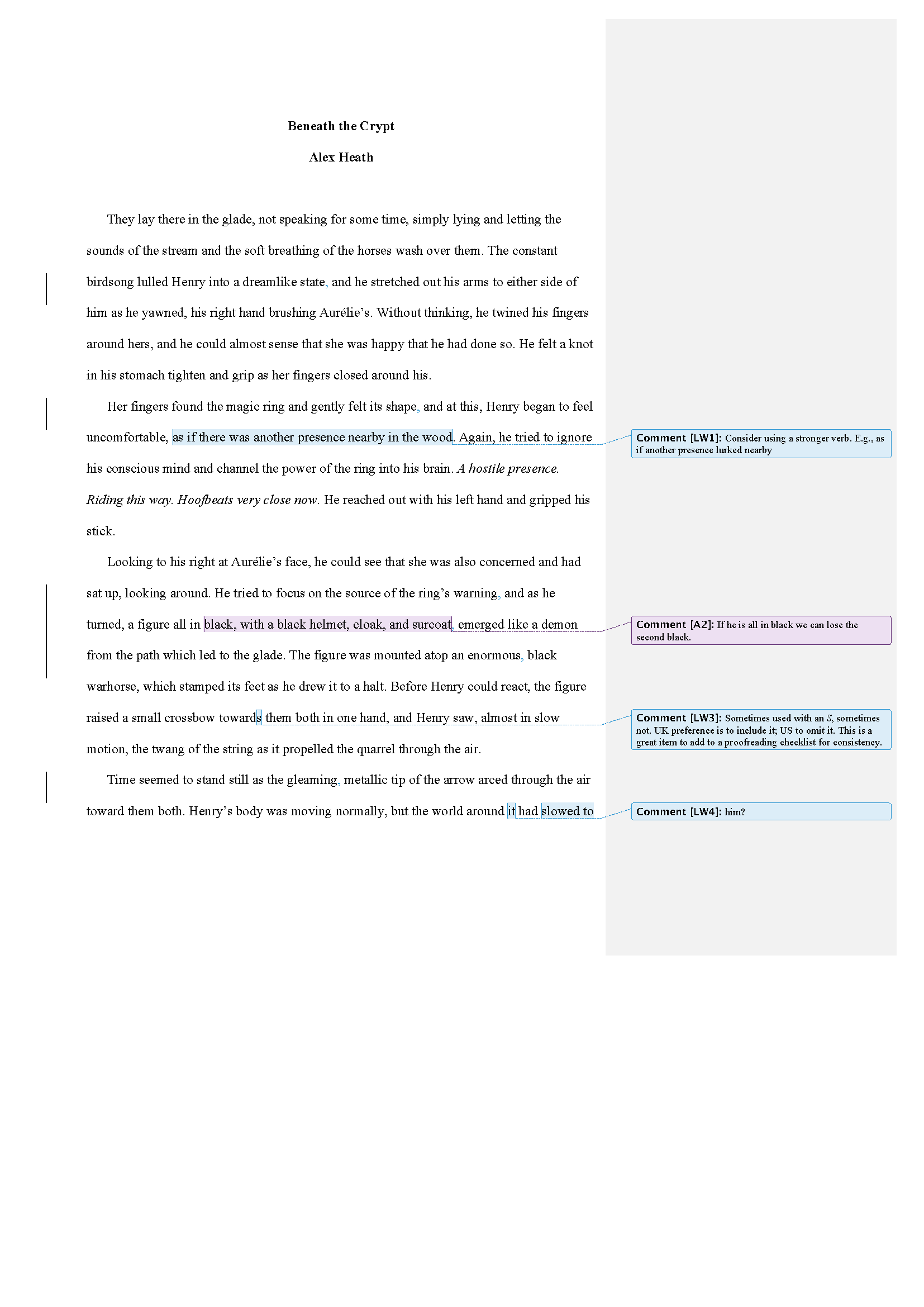

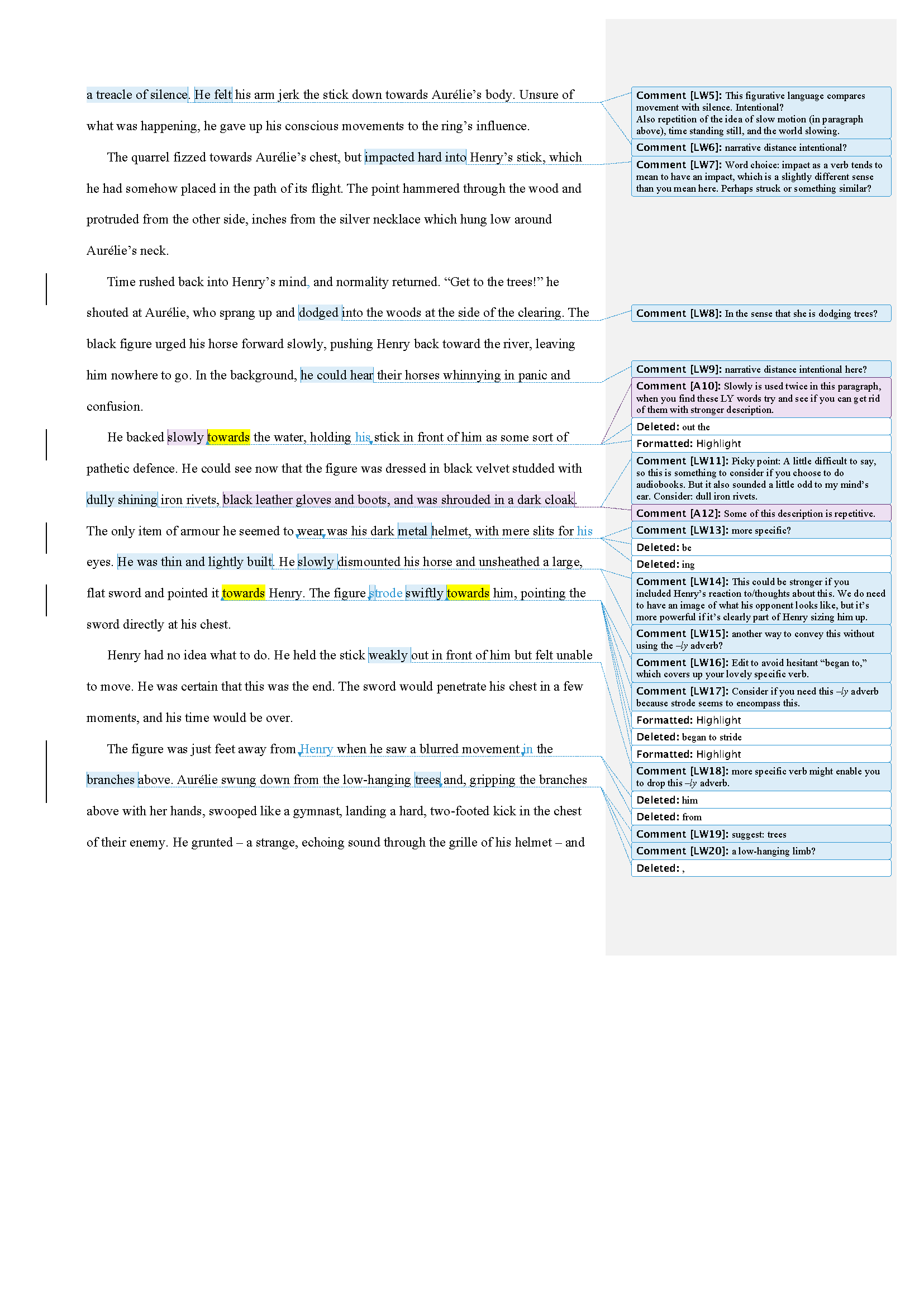

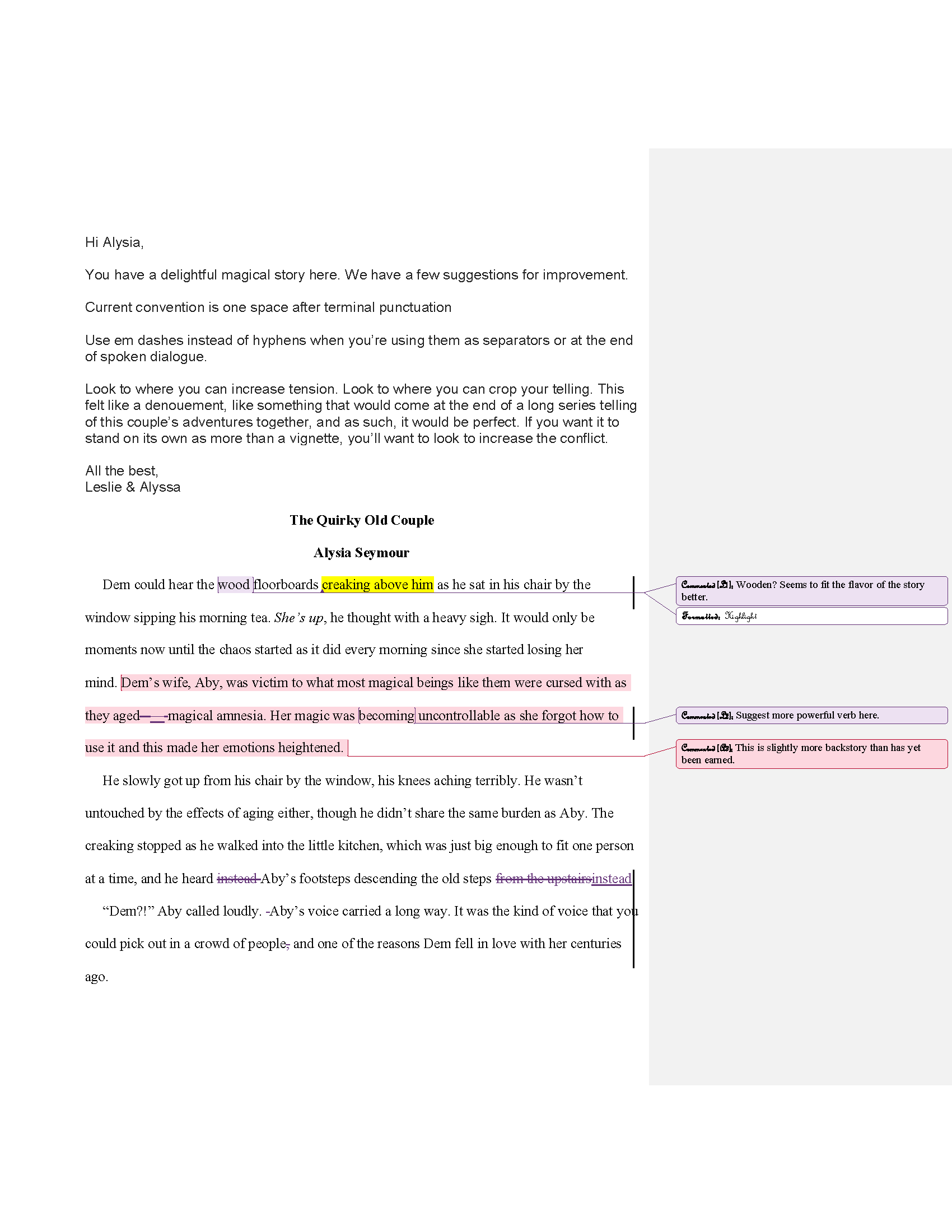

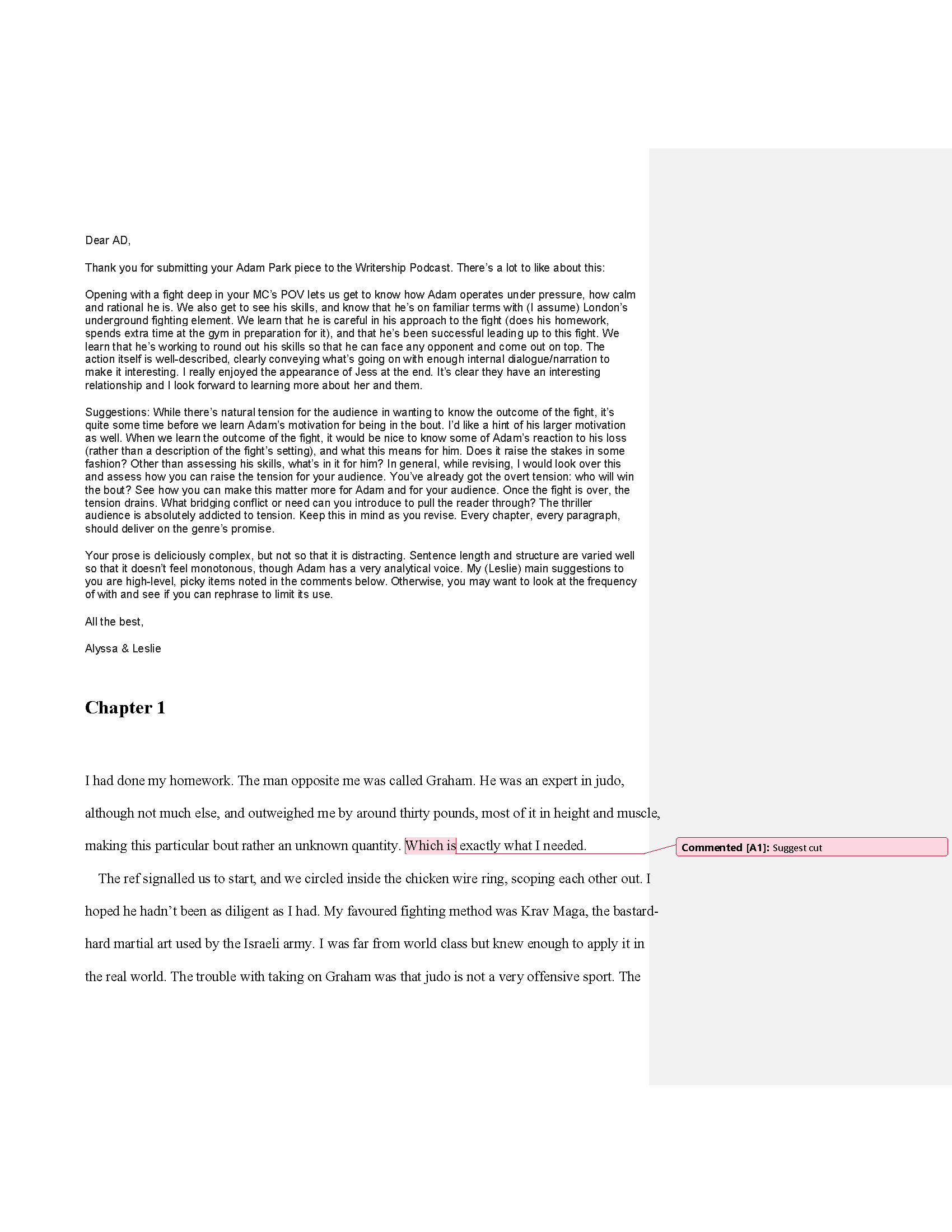

Dear Maxwell,

Thanks so much for your submission! Valerie and I both enjoyed reading your prologue and getting to know your characters and found that this scene had us fondly remembering Stand by Me.

I’m concerned after the fact that this may not be as helpful to you as we’d like it to be in light of the fact that the characters don’t appear again in the book and that we’re seeing this scene out of context more so than we normally do for a submission. I hope some of this discussion will be useful to you, though, if not with this scene than with others.

We looked at the scene through the Story Grid (SG) filter, and it’s certainly not the only way to assess a scene, but it’s one we’re both familiar with and that we’ve found helpful. I can’t speak for Valerie, but for my part this framework provides specific and actionable feedback that’s better than a vague sense of something’s not quite right here. Shawn Coyne developed this tool out of necessity. He needed a way to show authors how to fix their stories so that they could become best sellers because acquiring a certain number of successful books every year was a requirement of employment. But it also makes sense to me in light of what I know about story and where stories come from and why we tell them. I could go on about that, but this is meant to be a written critique of your scene. I could see how this might feel like unwarranted criticism, though, so I wanted to explain this.

I want to make it clear that in our assessment we don’t speak for Shawn Coyne, and this isn’t an official SG pronouncement. With these caveats, we present one way you could look at the scene using this framework.

The Story Grid has five commandments of story and one “little buddy”:

- Inciting incident: something happens that throws the character or world out of balance.

- Progressive complications: escalating degrees of conflict related to what the main character in the scene wants (sometimes to regain the status quo, sometimes something else).

- Turning point (little buddy of the second commandment): a point where someone acts or information is revealed that forces the character to make a decision.

- Crisis: the dilemma that the character faces that can be distilled this way: the best bad choice (like the lesser of two evils) or irreconcilable goods (two positive but mutually exclusive options).

- Climax: the moment when the character acts based on his decision.

- Resolution: shows the world after the character has made his choice.

If we look use this framework in the scene before us, we could break it down this way:

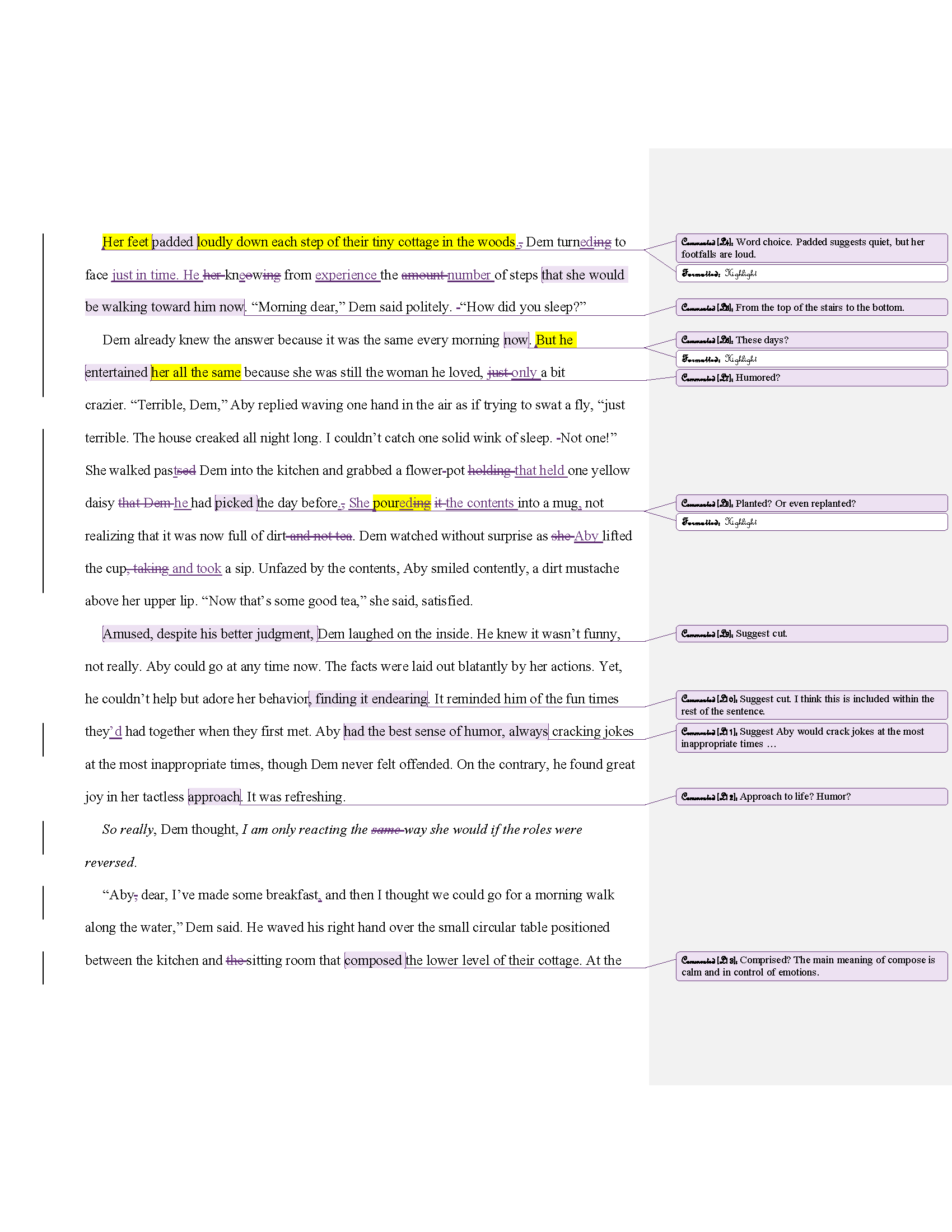

- Inciting incident: Mikey decides at long last that he will jump.

- Progressive complications: Depends on who the main character in the scene is. Anthony wants Mikey to jump. It’s not altogether clear what Mikey wants because he says he will jump, but then seems to have second thoughts. Our discussion on this point is pretty speculative.

- Turning point: This is another point where we’re not clear. Again, it depends on who the main character is in the scene. We get a closer view of Anthony, so let’s assume it’s him first. He wants Mikey to jump, and Mikey is stalling. If Mikey decides he’s not going to go, then we might have a turning point that requires some action on Anthony’s part to get what he wants, but Mikey never says he won’t. If we look at Mikey as the main character in the scene, there is no turning point for him unless, for example, he learns that there is a dead body in the water below.

- Crisis: This is a little confusing because we’re still left with the question of will Mikey jump or won’t he. Anthony doesn’t make the decision, and Mikey doesn't face a clear best-of-bad or irreconcilable-goods question (as far as we know because we’re not aware of what he’s thinking and feeling). Is he worried that Anthony would never speak to him again, for example? We don’t know what the consequences might be if he decides not to jump.

- Climax: Mikey decides to jump.

- Resolution: Mikey jumps. Jon has discovered a body in the water, which causes Mikey to vomit. This is where we would argue that the scene turns, but the conflict about Mikey jumping in the water has already been resolved, so this turn didn’t impact his decision.

Although I feel confident of this analysis of the scene, it doesn’t mean you have to agree with it. It’s your story, no one knows it like you do, and I’m well aware that I could have missed something. I also think that all the elements are here for a scene that works under this construct, that you could shift the discovery of the body, but you should do what feels right to you.

The analysis that I feel less confident about is whether this works as a prologue for your story because I don’t know what happens later to see how it fits in. My biggest concern, which we shared in the episode, is that the reader might wonder what happened to those kids from the prologue. Does that matter? It depends on what comes later. The only thing I would add after the fact is a consideration of Chekov’s gun, but again that could only be assessed in light of the whole story. If we had an omniscient POV showing the boys from a distance and revealing how sometimes things go wrong who saw the boys from a distance without our getting attached to them and noted how it could be dangerous (for the reasons cited), but that mostly this is a great place to swim, then that would appear to be more relevant to the overall story, but again, it’s hard to say without knowing where the story goes from here.

Thanks again for your submission, Maxwell! It presented a fun challenge for us!

All the best,

Leslie

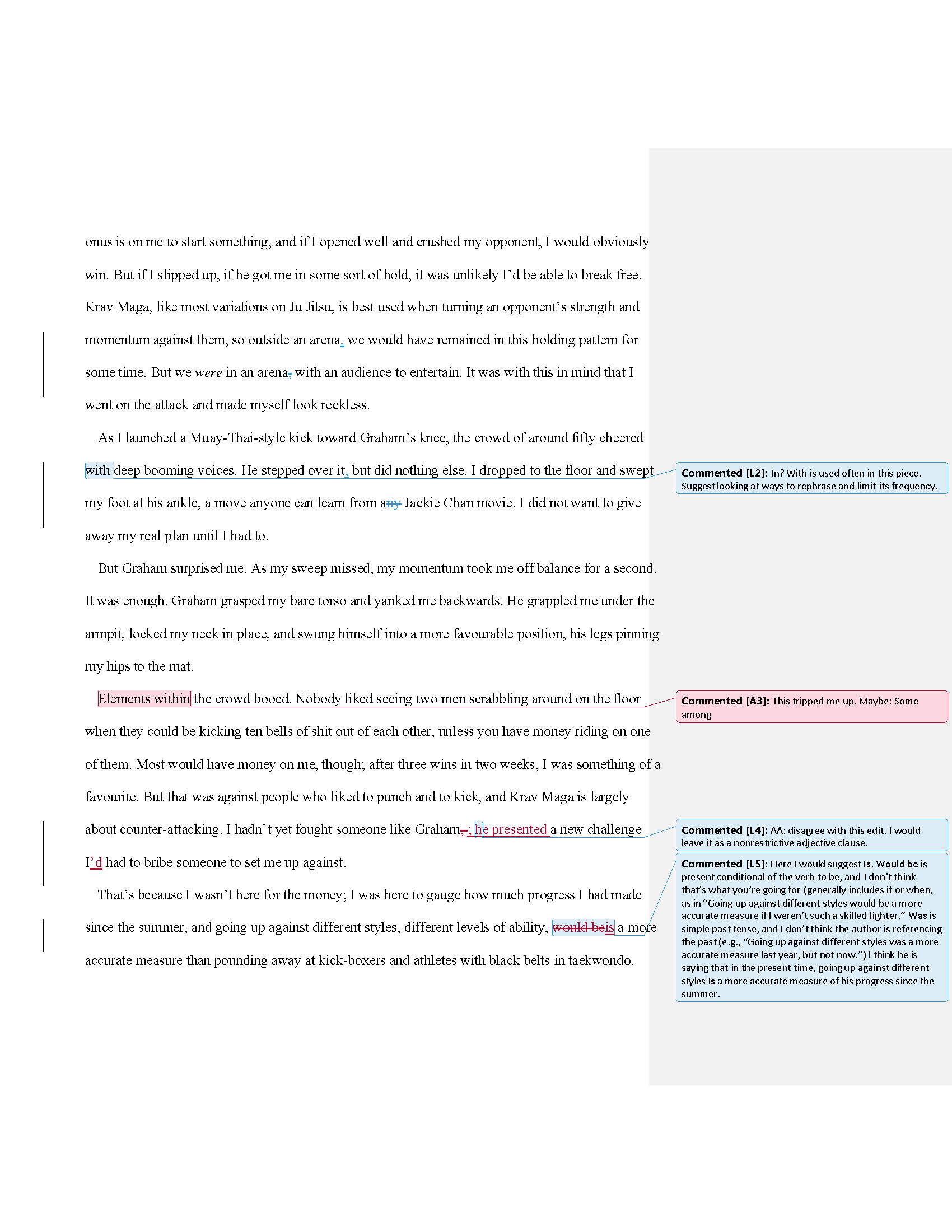

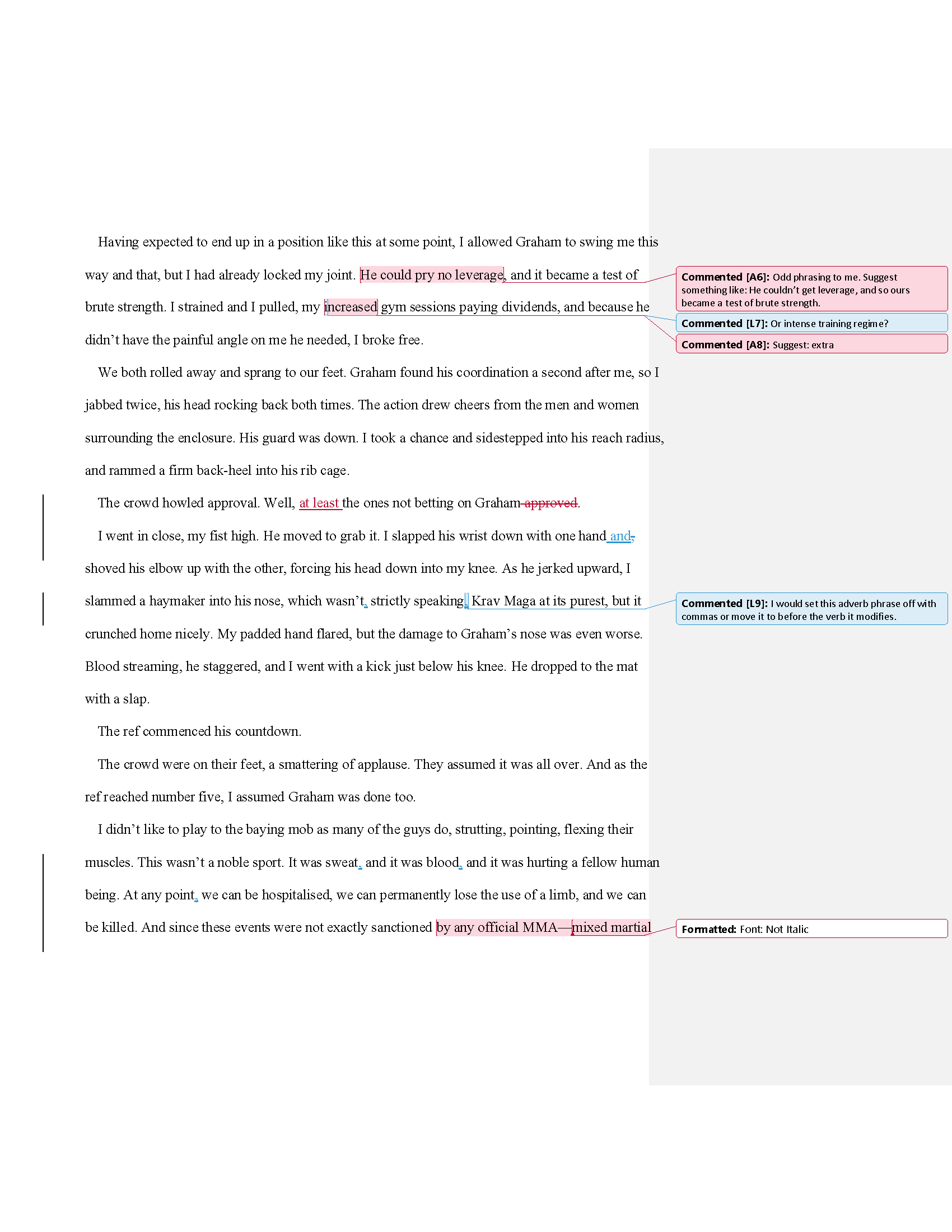

This Week's Submission

Image courtesy of [CREDIT GOES HERE]/bigstockphoto.com.