In this episode, fiction editors Leslie and Valerie critique the first chapter of The Arctic Compass, a middle grade fantasy novel by Ryan Gannon. They discuss how to check your opening scene for tension.

Listen to the Writership Podcast

About Our Guest Host

Clark is away for a couple of weeks, but our friend and fellow editor, Valerie, has graciously agreed to jump in and help out. You may remember Valerie from episode 105.

Valerie Francis is a best-selling indie author, story editor, and creative entrepreneur. After 20+ years in various writing-related careers, she published her first novel (a middle grade fantasy) in 2015. Upon hearing that J.K. Rowling sold 1,500 books her first year, Valerie set out to match that sales goal and, as a complete novice to the industry, hit her target in eight months. Her children's and women's fiction novels currently sell in over 10 countries.

Valerie's helps elementary schools foster a love of reading in their students, and she works with authors to develop their novels.

Valerie named her company Fifth Hammer Books, a reference to the myth of Pythagoras and the blacksmith's shop, because she believes that the most beautiful art is made, and the most important work is done, when the rules aren't followed. The Fifth Hammer is a reminder that the best ideas, like the best stories, work precisely because there is tension.

Learn more about Valerie and how she adds dissonance here.

Wise Words on Narrative Tension

“Narrative tension is often described as “the reason you turn the page”—in other words, the reader’s desire to know what happens next.

Narrative tension has three components: anticipation, uncertainty, and investment. … [T]here are different ways to create each component, and the way you mix them together will determine the flavour of the narrative tension in your book. Think of it like a stew: stew always contains a liquid base, solid ingredients, and seasonings, but your choices as the cook determine whether it’s an Irish Stew or a Cajun Gumbo.

Narrative tension should not be confused with conflict. Conflict is when characters are placed in opposition with other characters or with their circumstances. Conflict on its own does not guarantee narrative tension, and narrative tension doesn’t always come from conflict.

Narrative tension should also not be confused with pacing, which is the speed at which you tell the story. A fast or slow pace can support tension, but pacing alone doesn’t create tension.”

Mentioned in the Show

Here is a great post on narrative tension.

Here is another one!

Editorial Mission—Check for Tension

Tension is the vehicle that pulls your reader through the story. When people talk about tension, they often mention conflict, stakes, and pacing. These are all important and related to tension, but how do you create it, what are the elements? As Saul Bottcher mentions in the quote for the episode, it’s composed of anticipation, uncertainty, and investment.

This week, we want you to check your story’s opening for tension.

- Have you set up the possibility that something interesting is going to happen?

- Have you left room for uncertainty? Is there an open question in the reader’s mind?

- Have you added reasons for the reader to care about what happens?

If you’re lacking any of these elements in your opening scene, be sure to augment them.

Editing Advice to Our Author

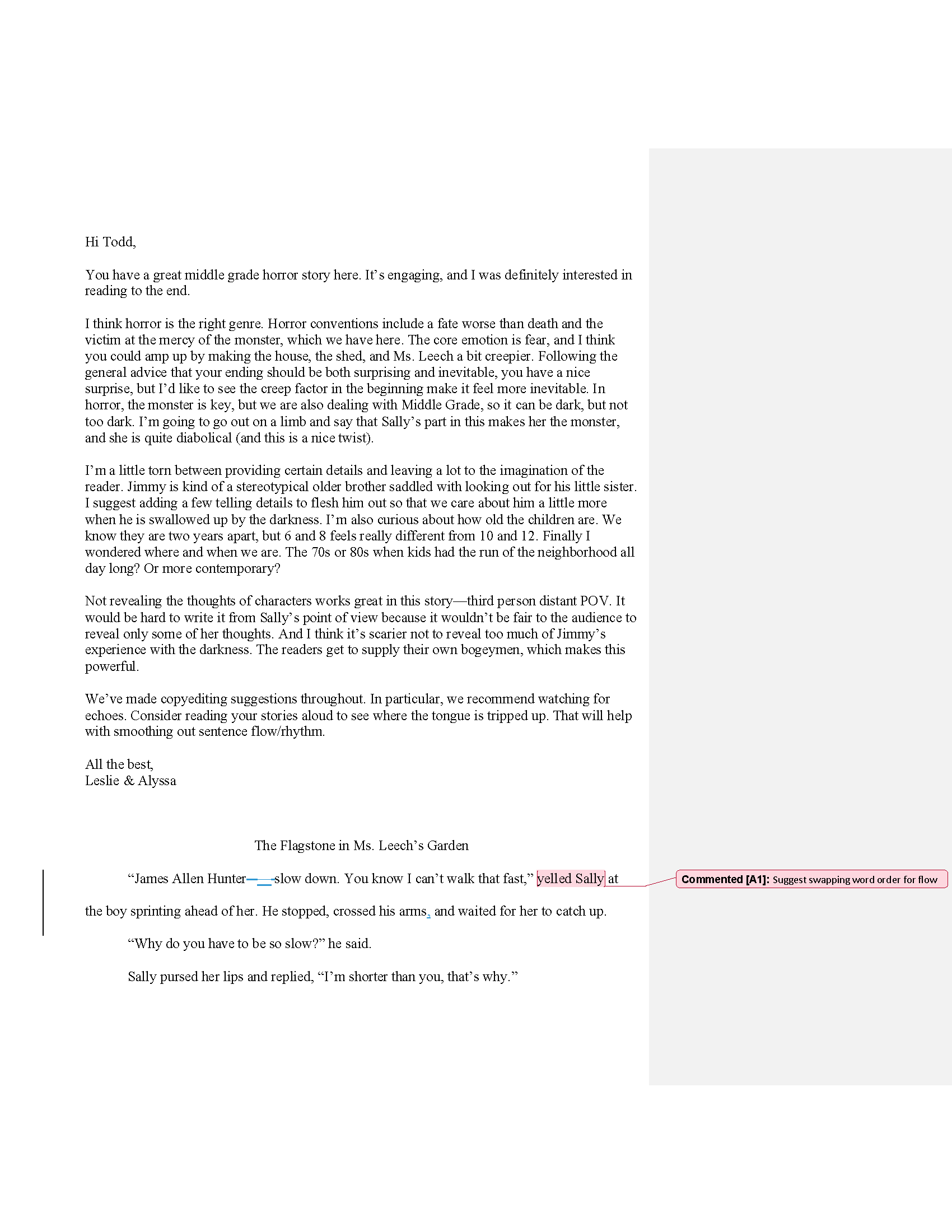

Dear Ryan,

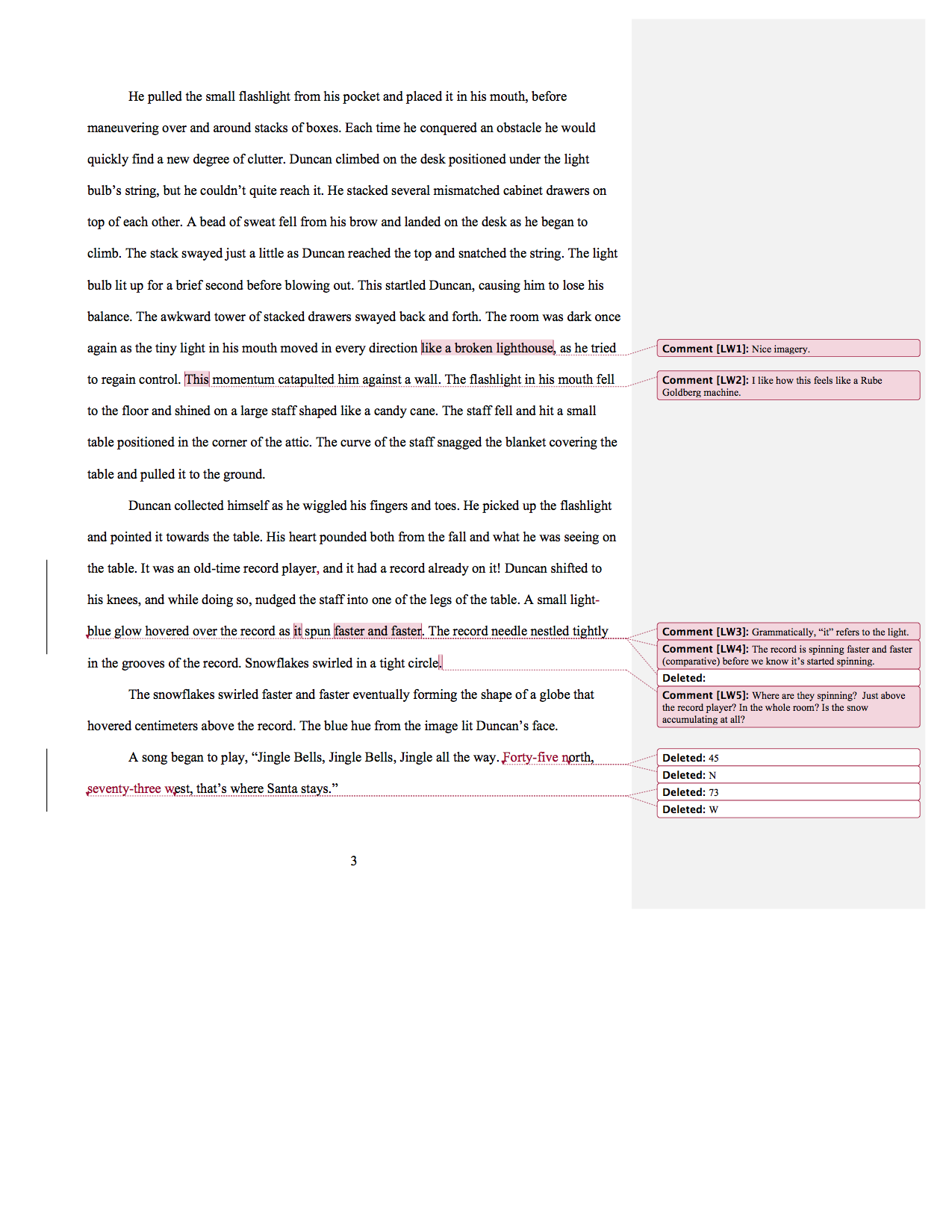

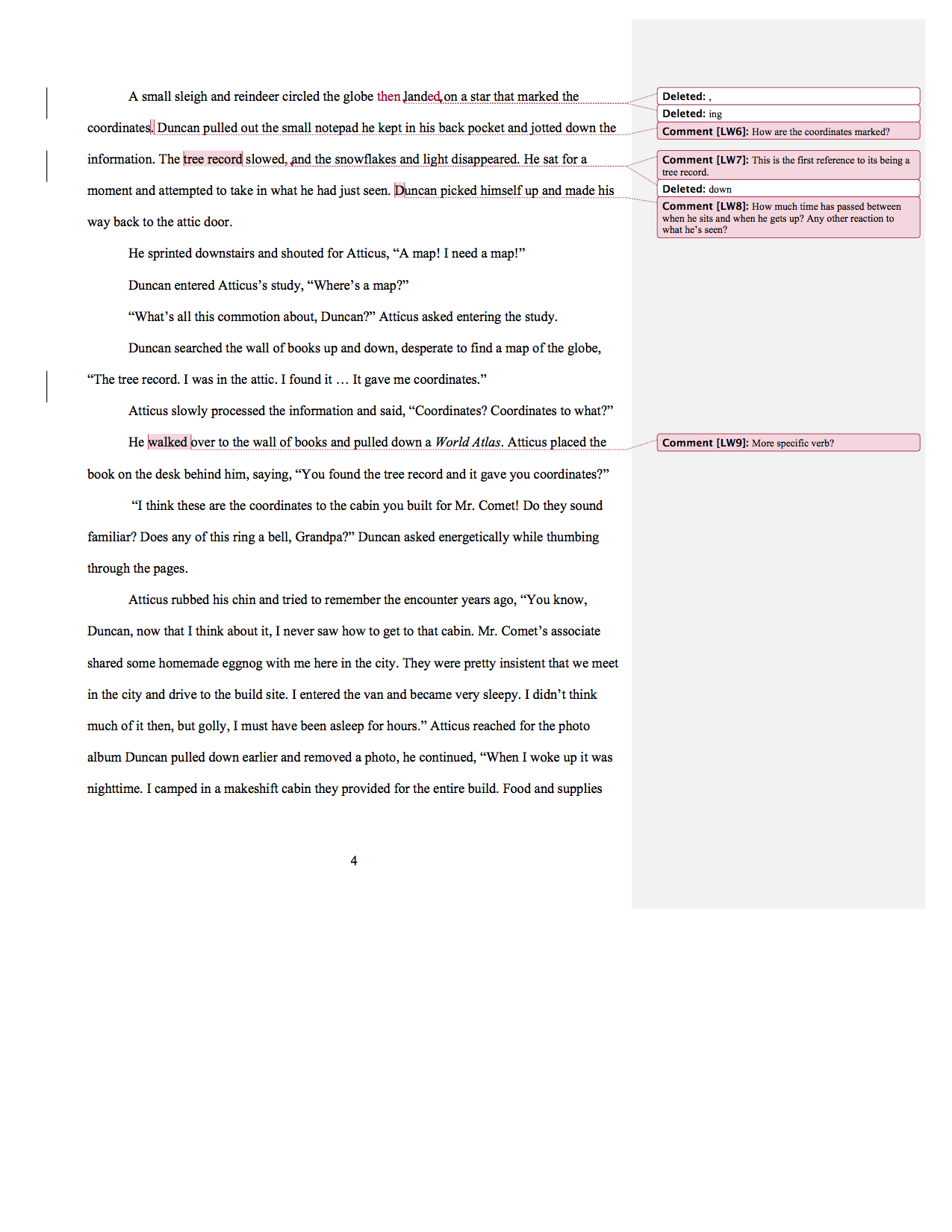

Thank you so much for your submission. This is such a delightful premise for a story, one that young readers would really enjoy. The attic is a great setting in this scene, and the Rube Goldberg-like action is really fun. Valerie and I have some suggestions that we think could take the lovely elements you already have and make them even stronger.

One important point that Valerie shared as a middle grade author is that a book’s competition (particularly for young readers) is not another book. It’s all the devices. There is no difference between writing for an adult, teen, tween, or kid when it comes to the elements of a great story and getting the reader to turn the page.

Tension is vital in pulling your reader into the story right away. It can be tricky to develop, though, so I want to unpack it a bit. Tension is created when the character has a specific goal, we care about whether he attains it, and a question arises in our minds about whether he will be successful.

You can help the reader care about your character and whether he’s successful in several ways, and it helps to add layers of interest and empathy. The character can be likeable or similar to the reader or someone they know, but that isn’t the only way. The challenge the character faces could be like one we face, or we might simply be curious about how someone like the character will work out a complex and challenging problem. One of the best ways to make the reader care about whether the character is successful is to show us what he wants and why he wants it—very specifically. We all have desires, so we understand the feeling of wanting something badly. The object of the character’s desire could be something we wouldn’t ever pursue. What we relate to is the wanting, and a specific desire is more powerful.

Along those lines, we want to know what’s at stake for the character if he fails. It would certainly be tragic if the magic of Christmas were lost forever—that’s pretty universal for kids who celebrate the holiday, and that’s a great place to start. But when we have desires or stakes that are common, we can miss out on details that make them more compelling. Knowing what failure means to the specific character in specific circumstances helps us to relate more easily. Consider Charlie and the Chocolate Factory and what failing to attain the golden ticket would have meant to Veruca Salt compared to Charlie. This doesn’t mean that we don’t care about Veruca or people whose lives are easier, but a story about her would be more compelling if she risked losing something that meant a lot to her. The same negative consequences have different meaning and impact for different people, and that difference affects how the reader relates to and cares about the character’s efforts to achieve the goal.

Another aspect of tension is anticipation. When the character achieves his goals easily, the reader doesn’t have time to wonder or worry about whether the character will achieve the goal because it happens so fast. Stretching out the anticipation with obstacles and missteps will increase the tension so that your reader can’t help but keep reading.

If we put these elements together, Duncan is a likeable kid, but I suspect you could reveal more about him and his desire than we’ve seen. This is not to say you need to add loads of new material or present it in an obvious way, but it would be interesting to see more of what makes Duncan different from other boys in his world and what makes him care so much about finding Santa. What does he lose if Santa is lost forever?

Consider making the obstacles tougher for Duncan and making him stretch and work for what he wants. Middle grade readers have a lot going on because they aren’t little kids receiving the care and attention that their younger peers do, but they don’t have the autonomy of their older peers. Things are changing rapidly mentally, emotionally, and physically. And everything feels hard. A character who faces seemingly insurmountable challenges will naturally appeal to readers of this age, and they will want to keep reading to find out what happens to him.

Thanks again for sharing your magical story with us!

All the best,

Leslie

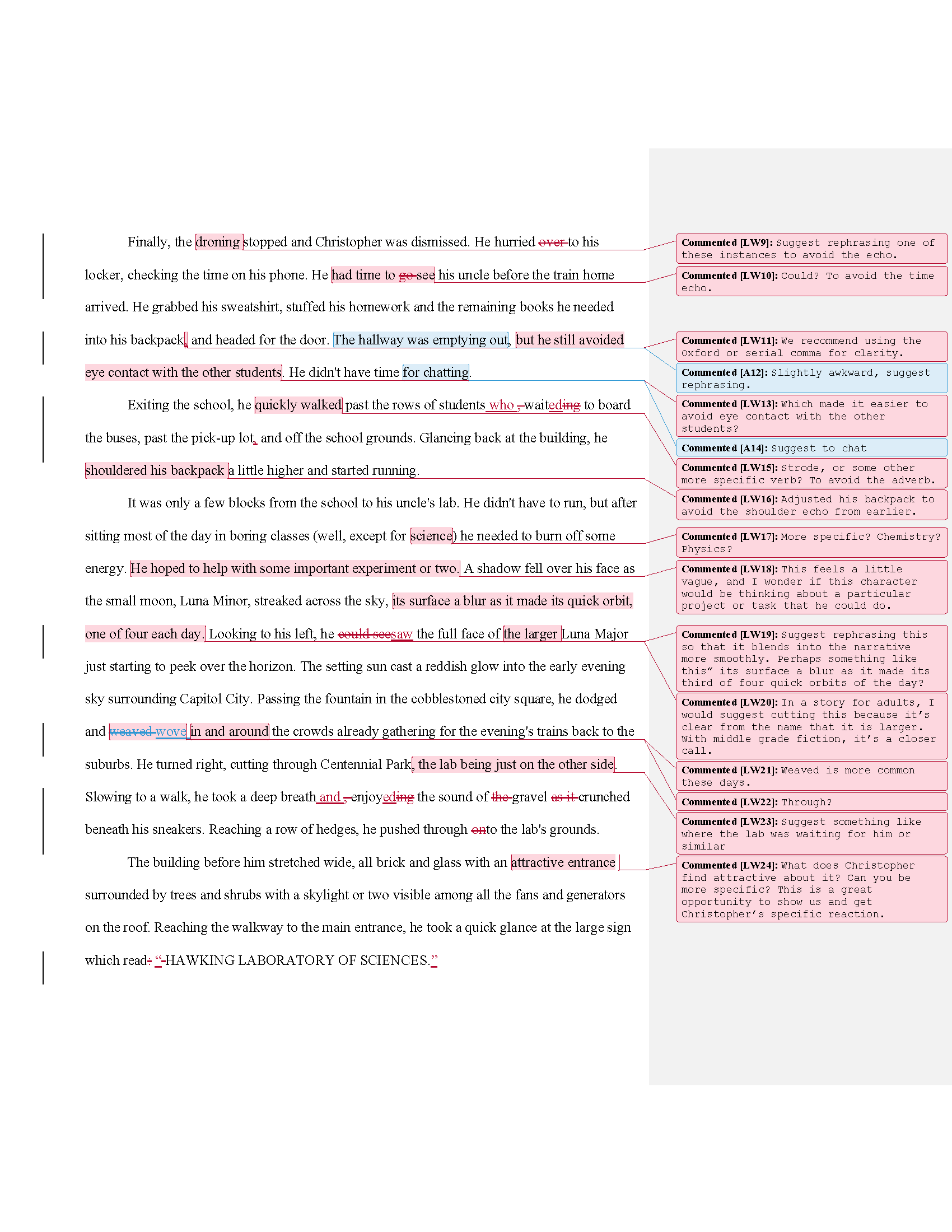

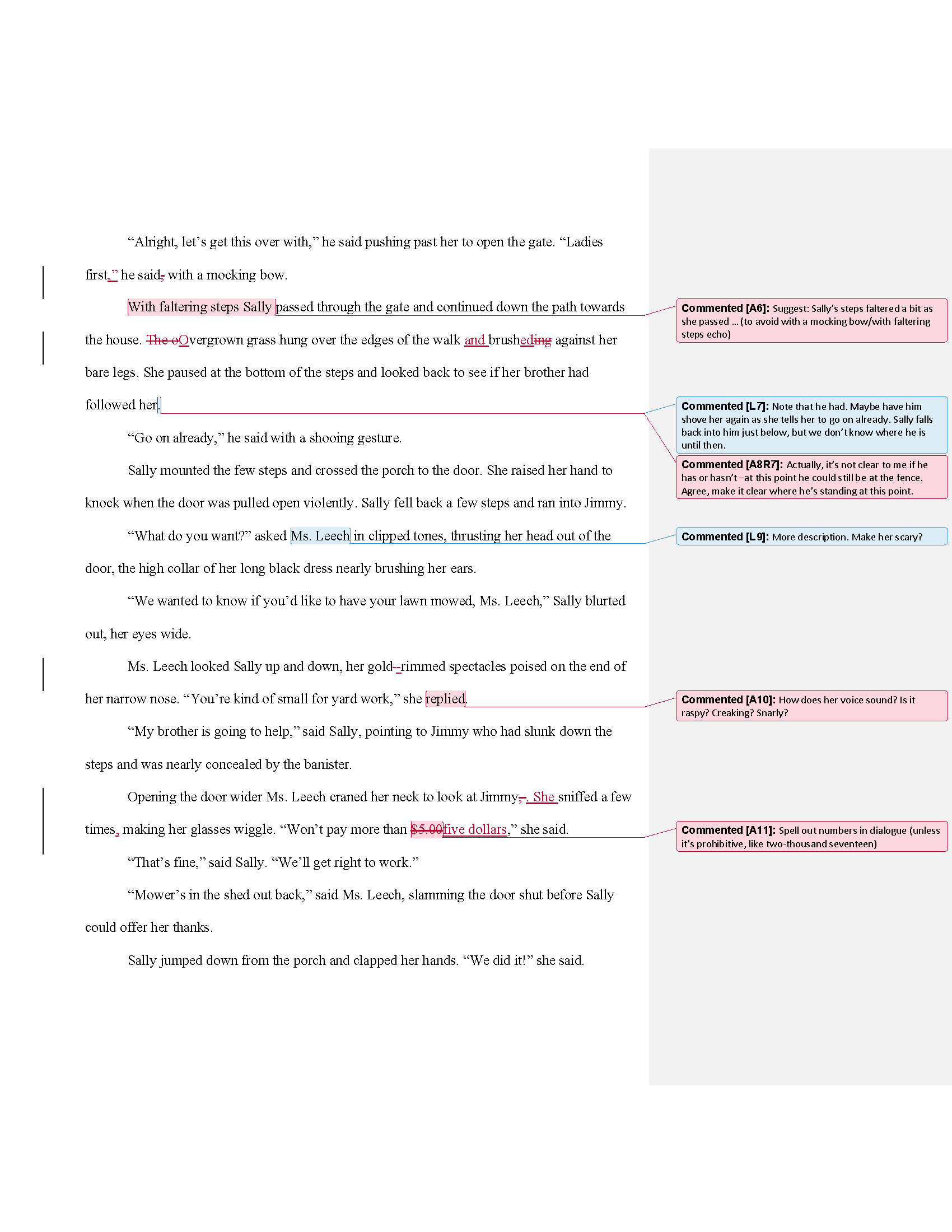

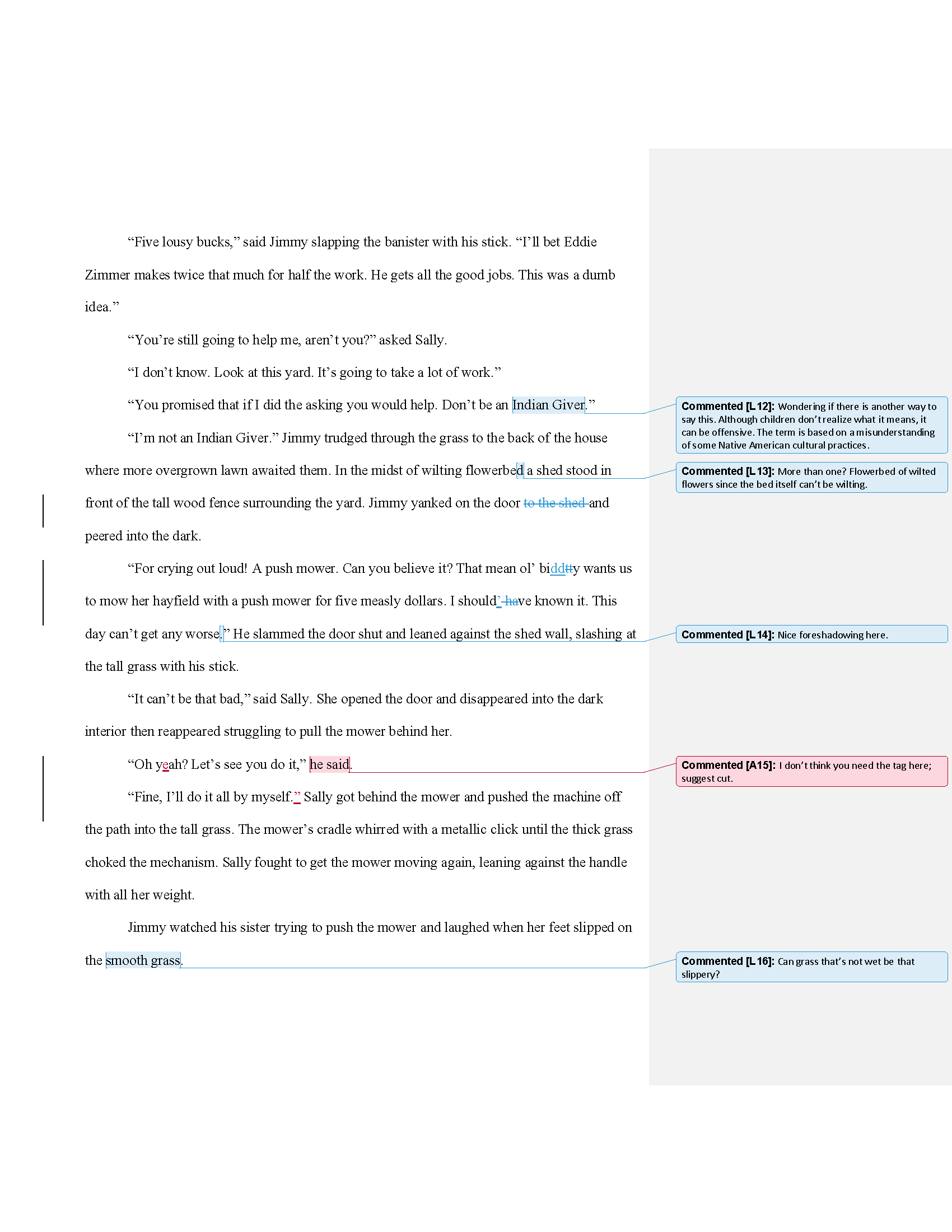

Line Edits for Our Middle Grade Story

Image courtesy of Aaron Amat/bigstockphoto.com.