Description

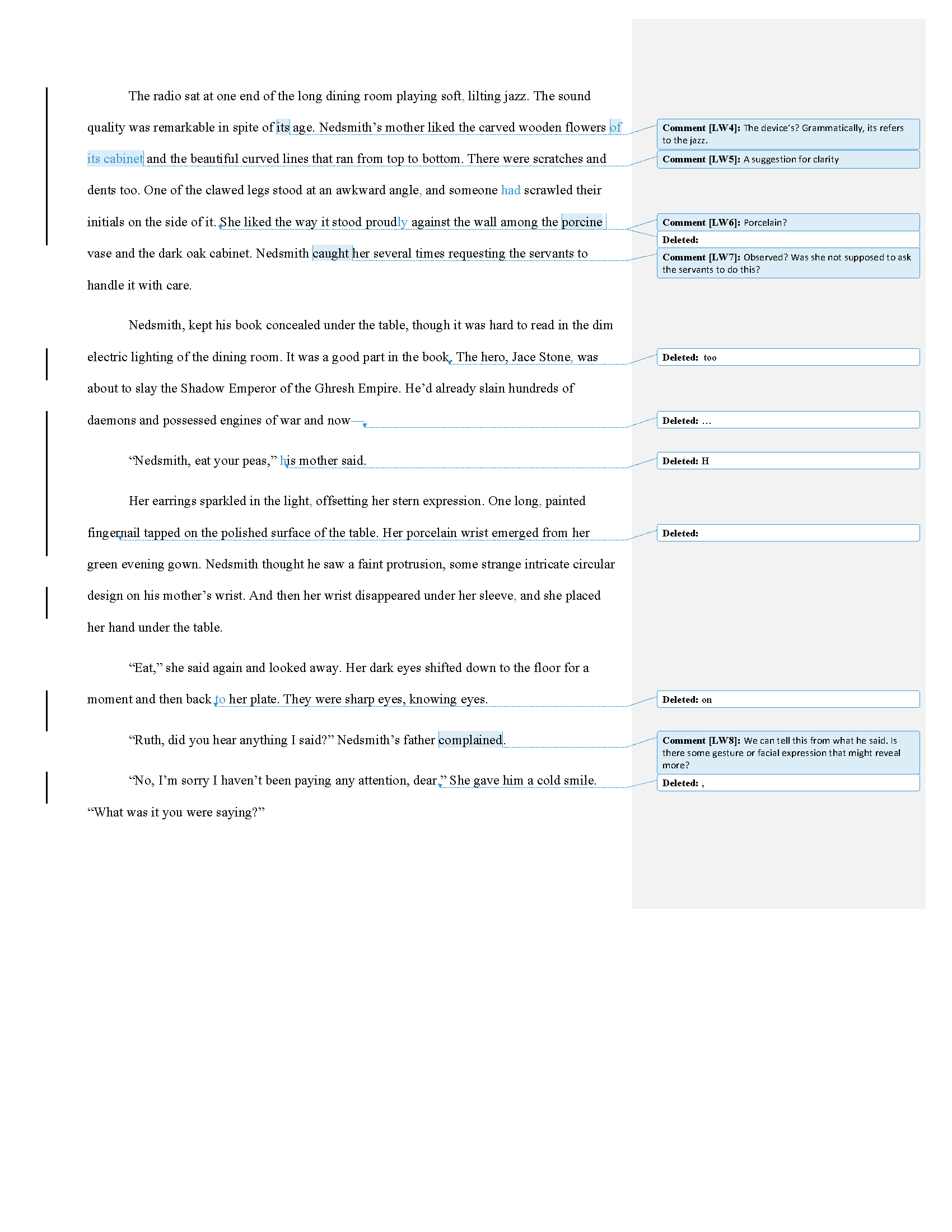

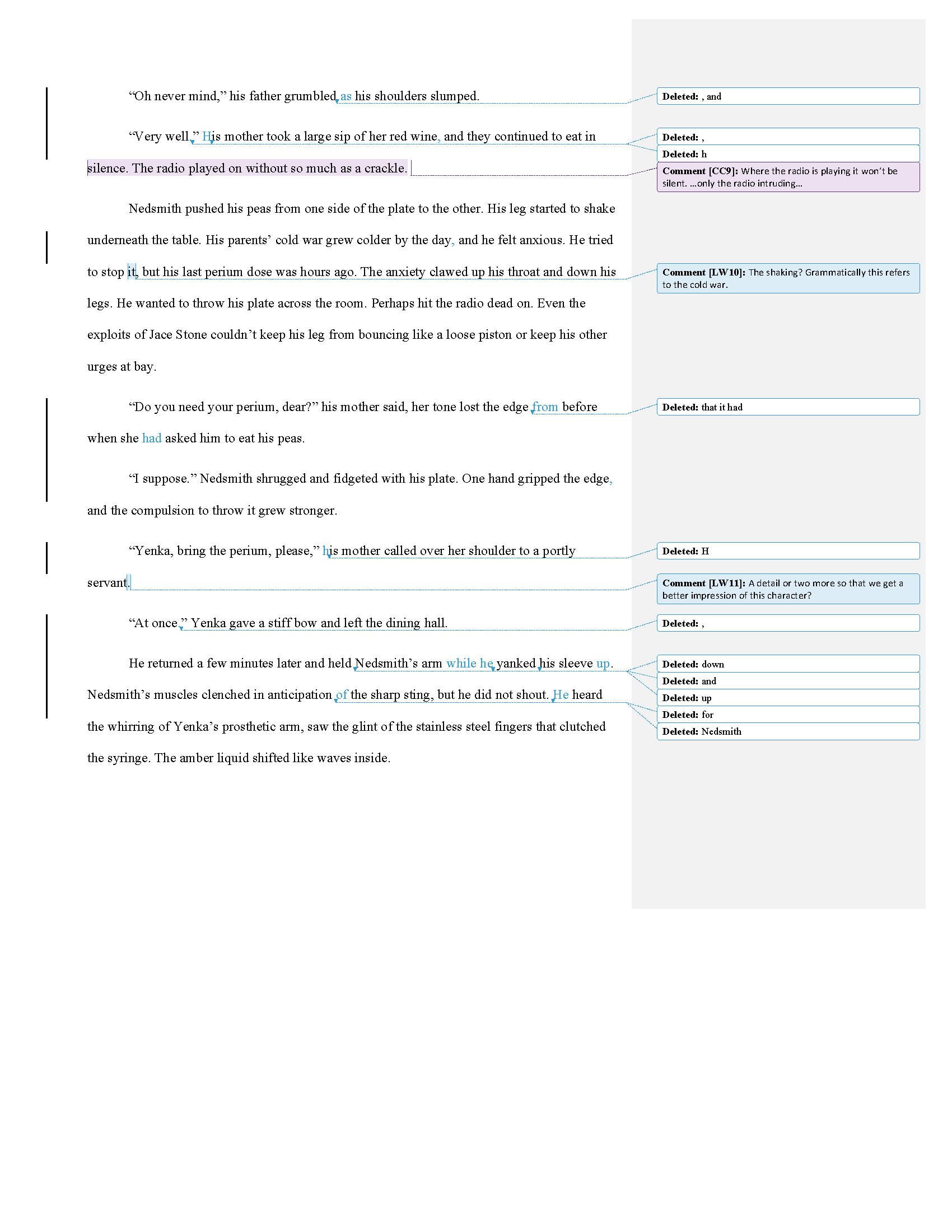

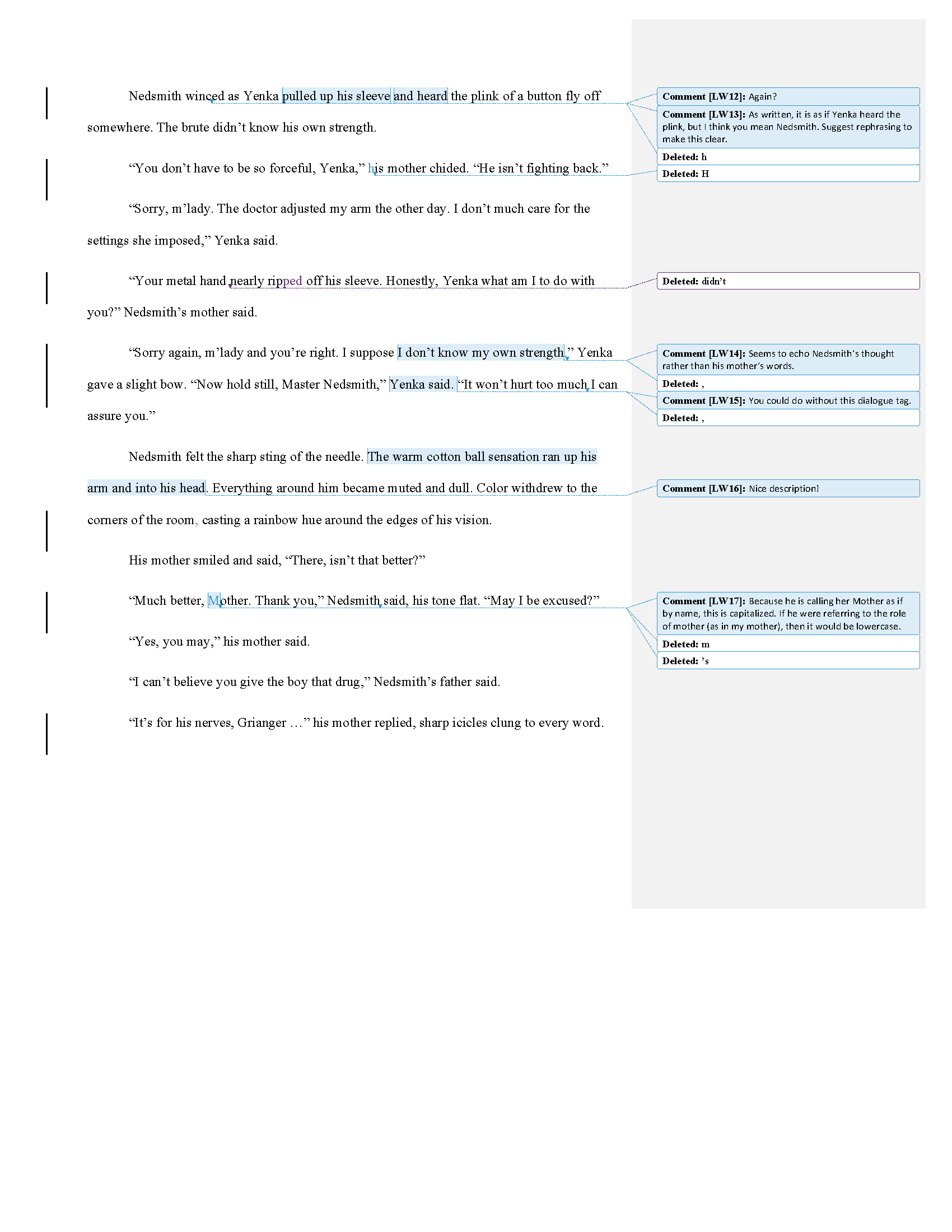

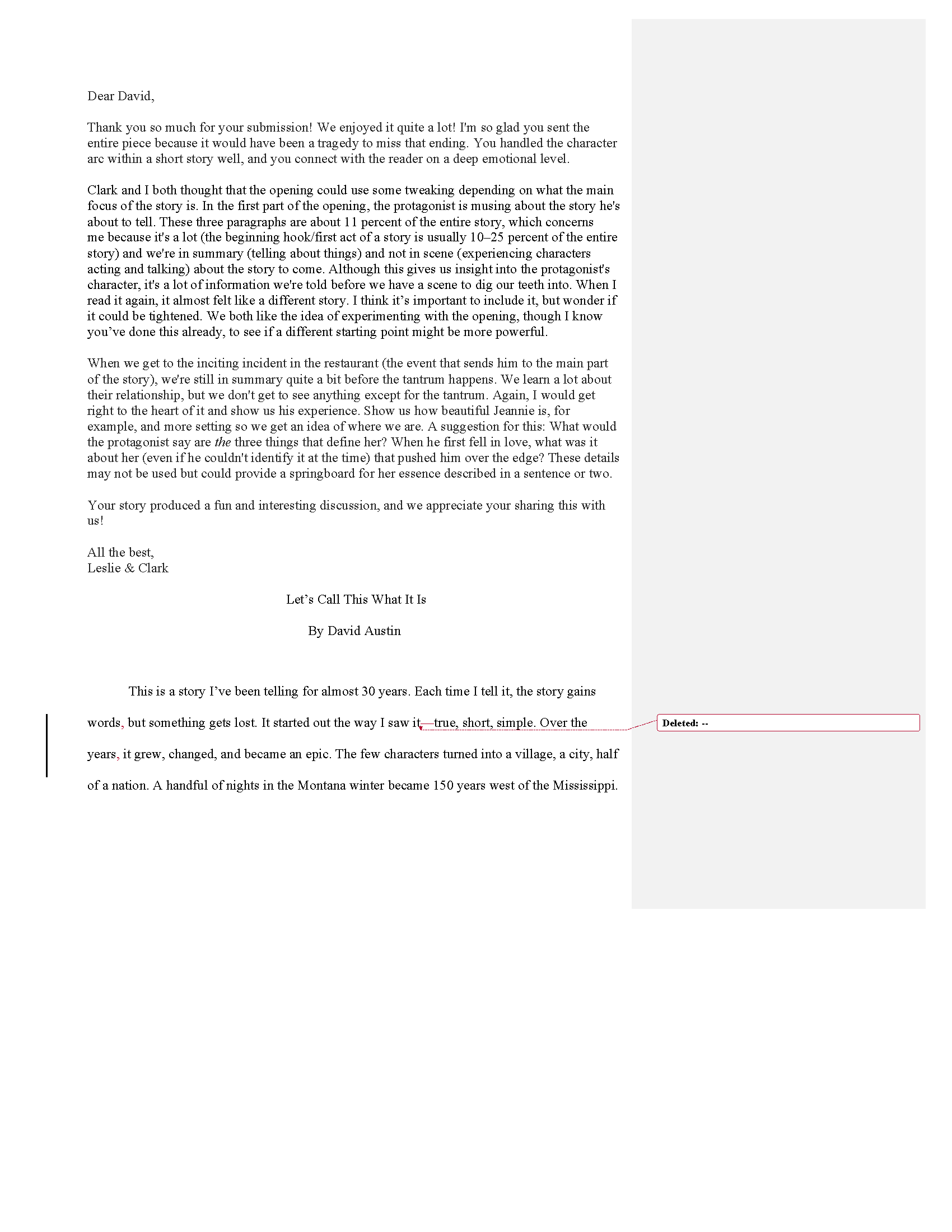

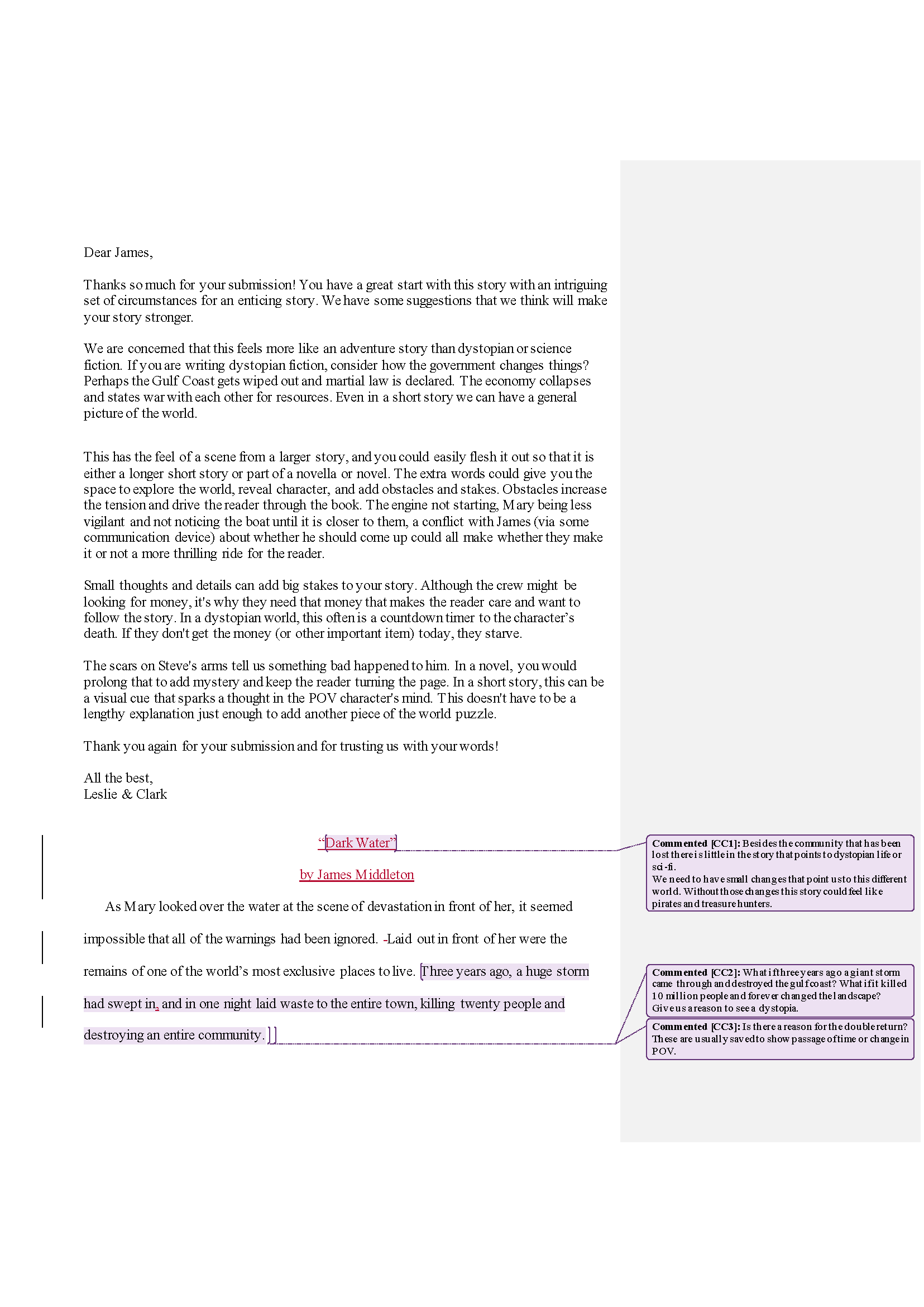

In this episode, Leslie and Clark critique the beginning of Edge, an as yet unpublished atompunk novel, by Ethan Motter. They discuss the ordinary and special worlds of the story, mysteries and questions, world building, scene and summary, and dialogue tags with similes to reveal emotion. They also talk about the importance of setting writing goals for 2017.

Listen Now

Show Notes

“It’s a good idea to make the Ordinary World as different as possible from the Special World, so audience and hero will experience a dramatic change when the threshold is finally crossed. In The Wizard of Oz the Ordinary World is depicted in black and white, to make a stunning contrast with the Technicolor Special World of Oz. In the thriller Dead Again, the Ordinary World of modern day is shot in color to contrast with the nightmarish black-and-white Special World of the 1940s flashbacks. City Slickers contrasts the drab, restrictive environment of the city with the more lively arena of the West where most of the story takes place. ”

Look for Leslie's post on setting writing goals here.

Editorial Mission—Ordinary World

Review your story’s opening for clues about the ordinary world. Keep in mind that just because we use world doesn’t mean you are limited to the setting (consider Pride and Prejudice, for example). Consider what the essence of the change will be once the inciting incident happens. How can you effectively demonstrate the contrast? What specific details will can you reveal that will allow the reader to experience the change?

Do you want editorial missions sent directly to your inbox?

Sign up below to join the podcast club and you'll never miss an episode—or an editorial mission—from the Writership Podcast!