If you cringe when people tell you what you must do to tell a great story, you’re not alone. But when you nail down your genre, you gain valuable information to help you plan, draft, and revise your story. In fact, it might be the most important decision you make.

Ep. 117: Shoe Leather: Eliminating Unnecessary Exposition

Ep. 115: Motivation-Reaction Units

Ep. 114: Inciting Incidents

Ep. 113: Intentional Sentence Construction

You have a wide variety of tools to support your story, including the words and sentence structure you choose. The trick is to understand when to use different tools to provide the reading experience you’re aiming for. Listen to this episode to find out how to make the most of your language choices.

Ep. 112: Flashbacks

Ep. 111: Experiment with Omniscient POV

Ep. 110: Self-Editing Your Fiction

Ep. 109: Where to Begin Your Story

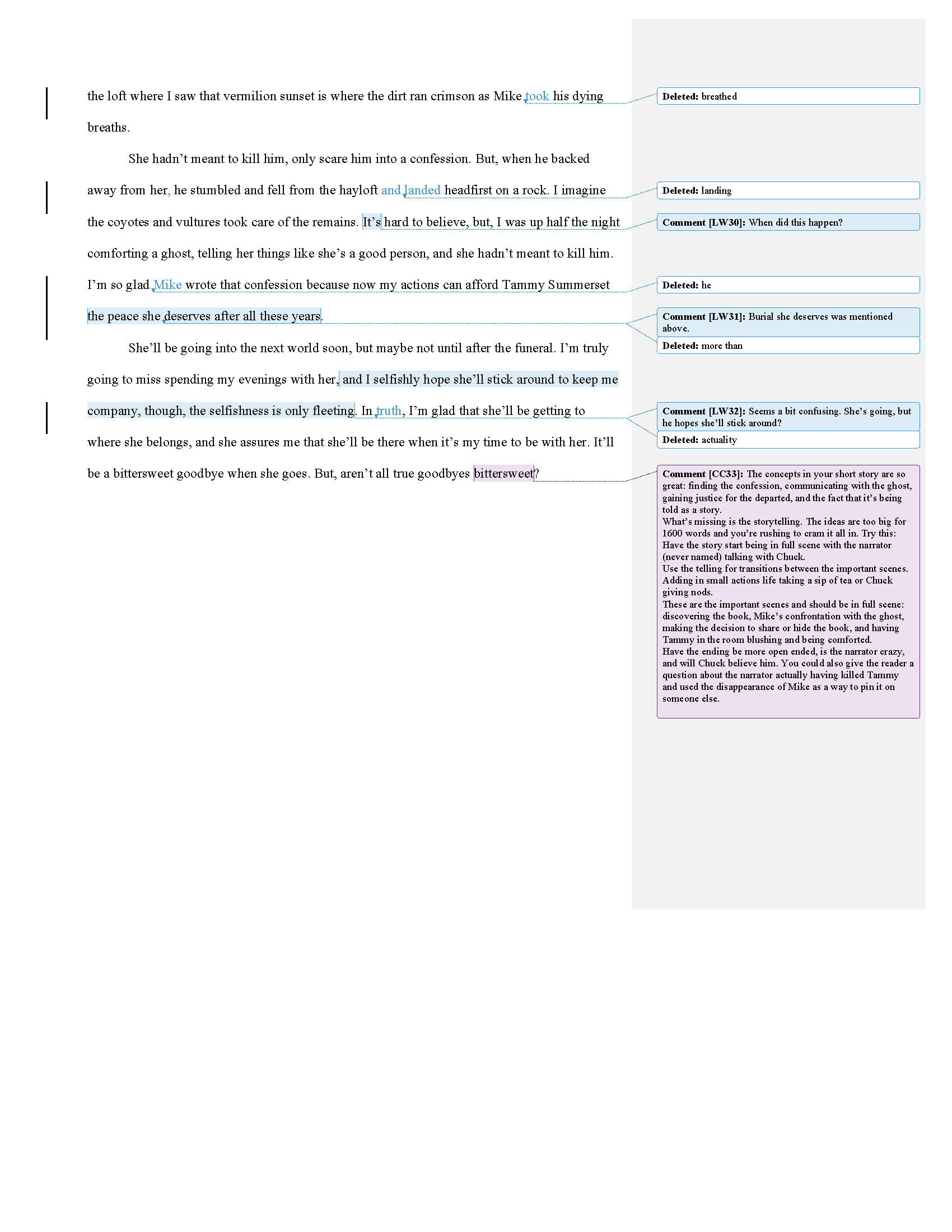

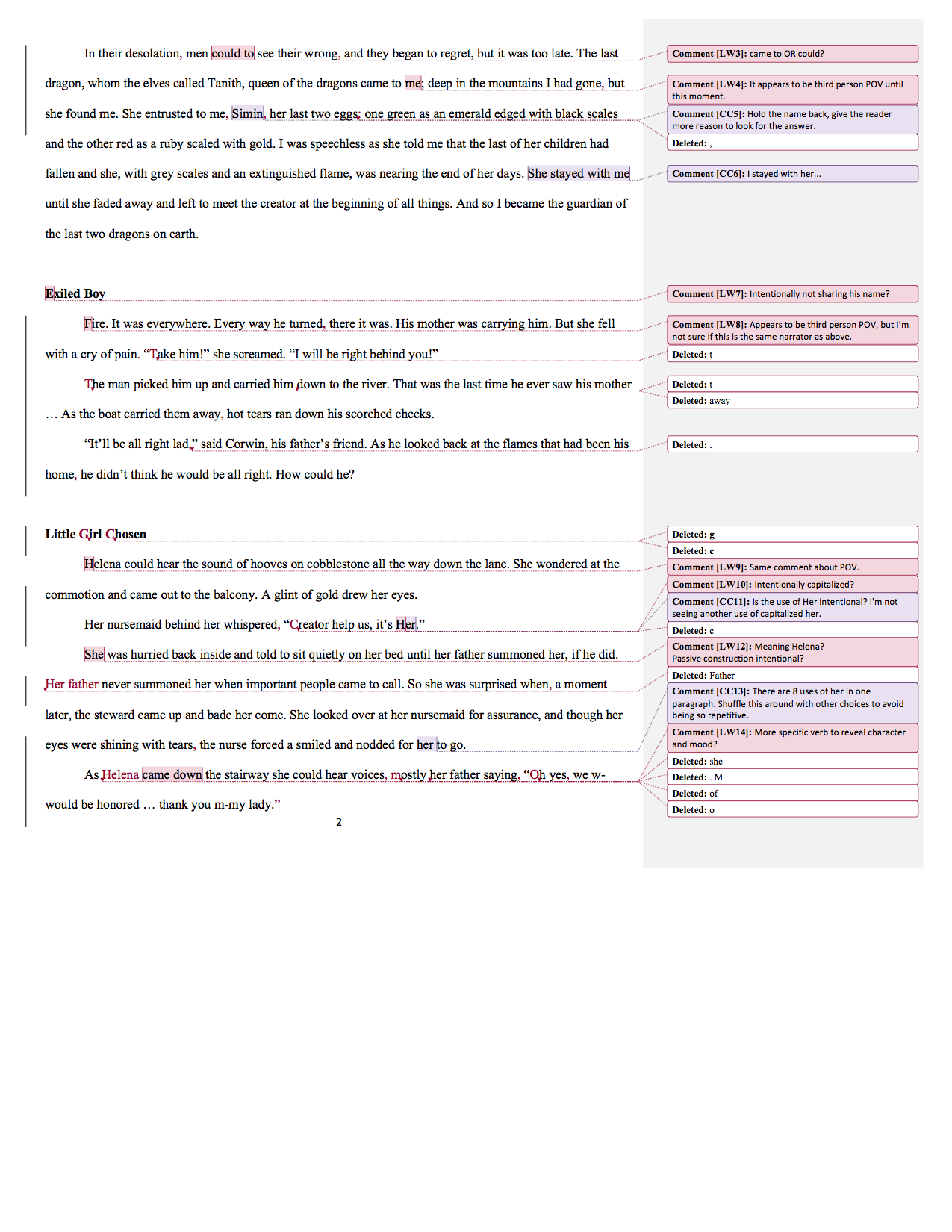

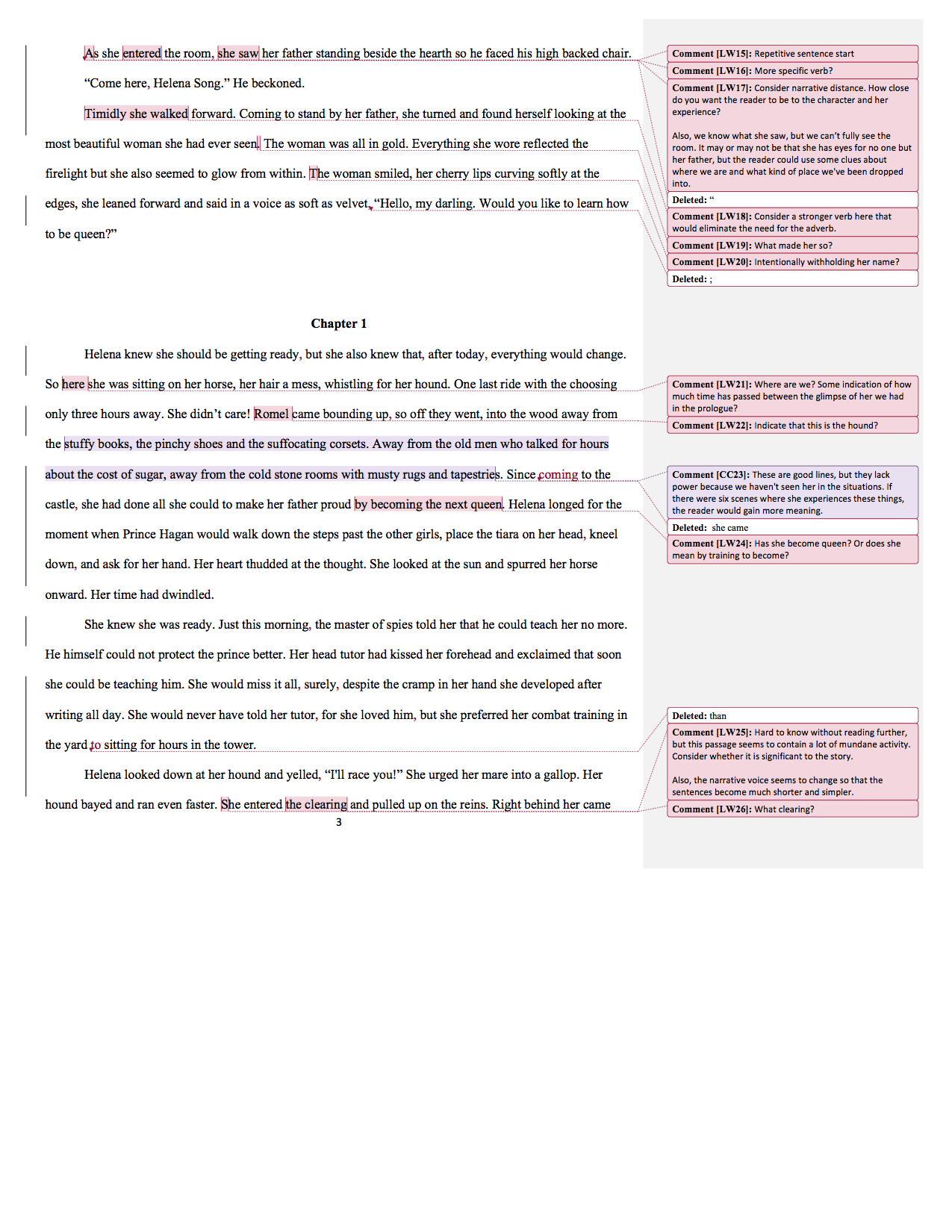

In this episode, fiction editors Leslie and Clark critique the prologue and first chapter of From the Flame, a fantasy novel by Kristen Franklin. They discuss where to begin your story. If all the events of the protagonist’s life were laid out in front of you, which is the most powerful moment to use for chapter one?

Listen to the Writership Podcast

Mentioned in the Show

Hire Clark for your developmental edit! Click here to find out more or email Clark.

Find an illustrated guide to writing scenes and stories here.

Wise Words on Starting Your Story

“But where should you start your story—and when—given that it makes such a difference in the story’s success or failure? For example, right now you’re in a room with a talking penguin, a woman with a gun, and someone hiding behind a potted plant. From your perspective, you might want to rewind events to a point where you can make more sense of it all. However, many writing instructors suggest starting the story as late as possible. What does “late” mean? It often means that moment at which maximum dramatic tension occurs without the loss of so much context about character, setting, and other elements that the drama is meaningless or confusing.”

Editorial Mission—Where to Begin Your Story?

Look at your story as a whole and consider where the protagonist is starting and where she ends up. What are the events that lead up to what happens in the story? Have you shown enough of the ordinary world to allow the reader to perceive the impact of the inciting incident? Have you started too early?

Editing Advice To Our Author

Dear Kristen,

Thank you so much for your submission. Helena is an intriguing character, and the opening of chapter one has me quite curious about her coming adventures. We expect princesses and queens to be trained in certain skills, but these don’t usually include combat and spying. This is a lovely twist that tells us that Helena isn’t a standard potential princess that we’re used to seeing in fantasy novels.

We have some suggestions that we think might make the opening stronger, but I want to preface this with a couple of caveats. This is an early draft, so you hadn’t had the opportunity to review the opening in light of how it ends. The beginning often changes dramatically once we get a better idea of what we’re writing toward.

It’s tricky to make suggestions about where to start, especially when we don’t know what follows, and prologues often don’t make sense at first because the reader is seeing events or characters out of context. Please consider our suggestions as representing options to consider. An editor reviewing your story would read the entire manuscript and understand how the events in the prologue fit.

The History of the World portion of the prologue didn’t seem critical at this point. It was a lot of information when we don’t yet know what’s important. If you refer to a time before the fires without explaining it, you create mystery that can pull the reader forward. It’s tempting to give the reader an explanation of the world when it’s unfamiliar to them, but consider waiting until the facts can provide the greatest impact, where its revelation will bring the protagonist closer to or further from her goal. Readers know they are entering a world different from their own, so you have the luxury to reveal your world strategically.

In Helena’s portion of the prologue, I didn’t feel as pulled into the story as I would have liked. Much as I love Helena as a character, I didn’t feel fully engaged with her until chapter 1. That’s when we get a characteristic moment in Helena’s ordinary world that is moments away from an event that could throw her life into chaos. We see her engaged in an activity she loves and we hear about her training. We also know about the big event to come, which raises all sorts of questions in the reader’s mind. The prince is supposed to choose his future wife, but will he choose Helena or someone else? He could flat out refuse to choose. Some other event could happen that changes everything. These possibilities make for a compelling opening where we’re eager to find out what happens next.

Again, this is something to consider in light of what you know about how the rest of the story unfolds. Thanks again for your submission, Kristen!

All the best,

Leslie

Line Edits for Our Fantasy Story

Image courtesy of kenny001/bigstockphoto.com.

Ep. 108: Narrative Drive—Compelling Your Reader to Turn the Page

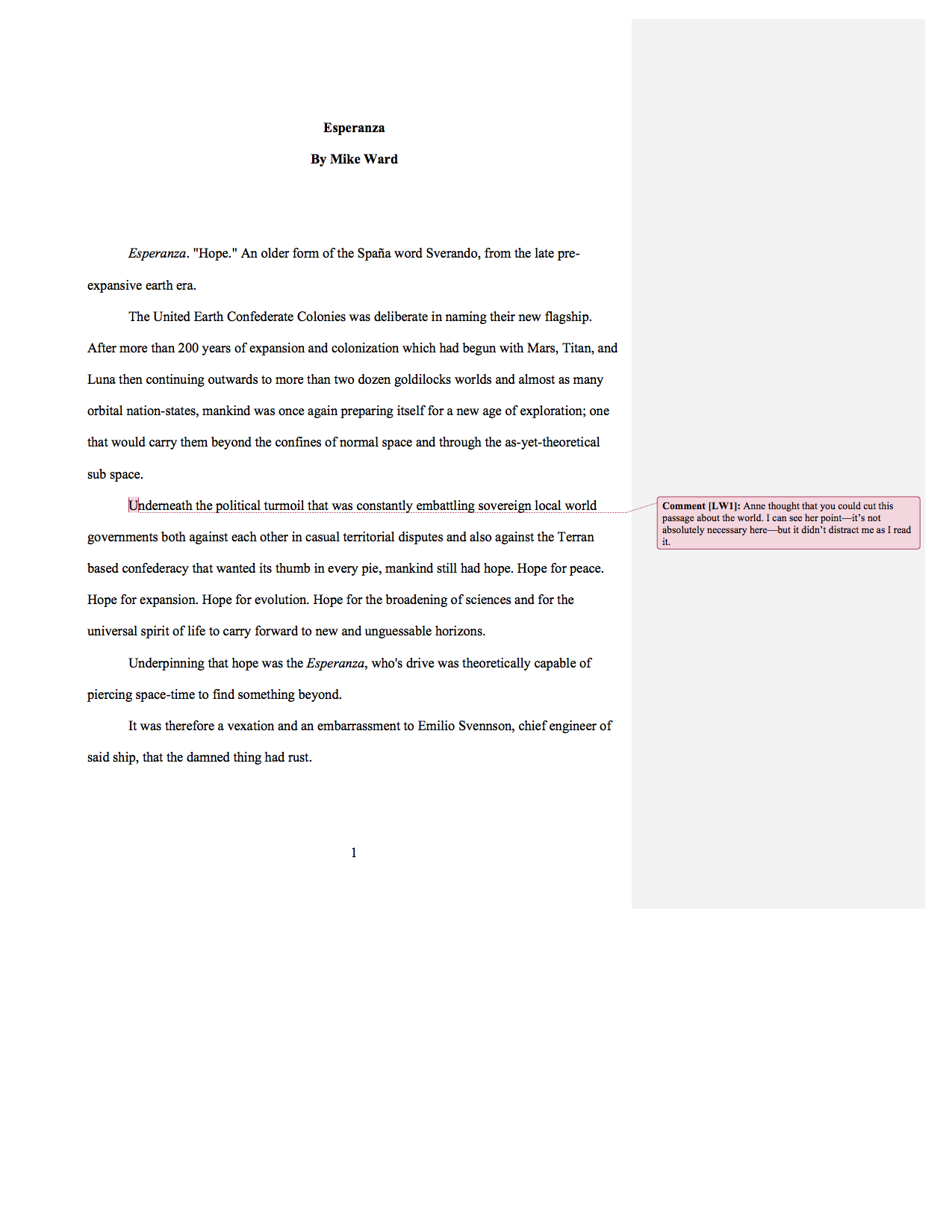

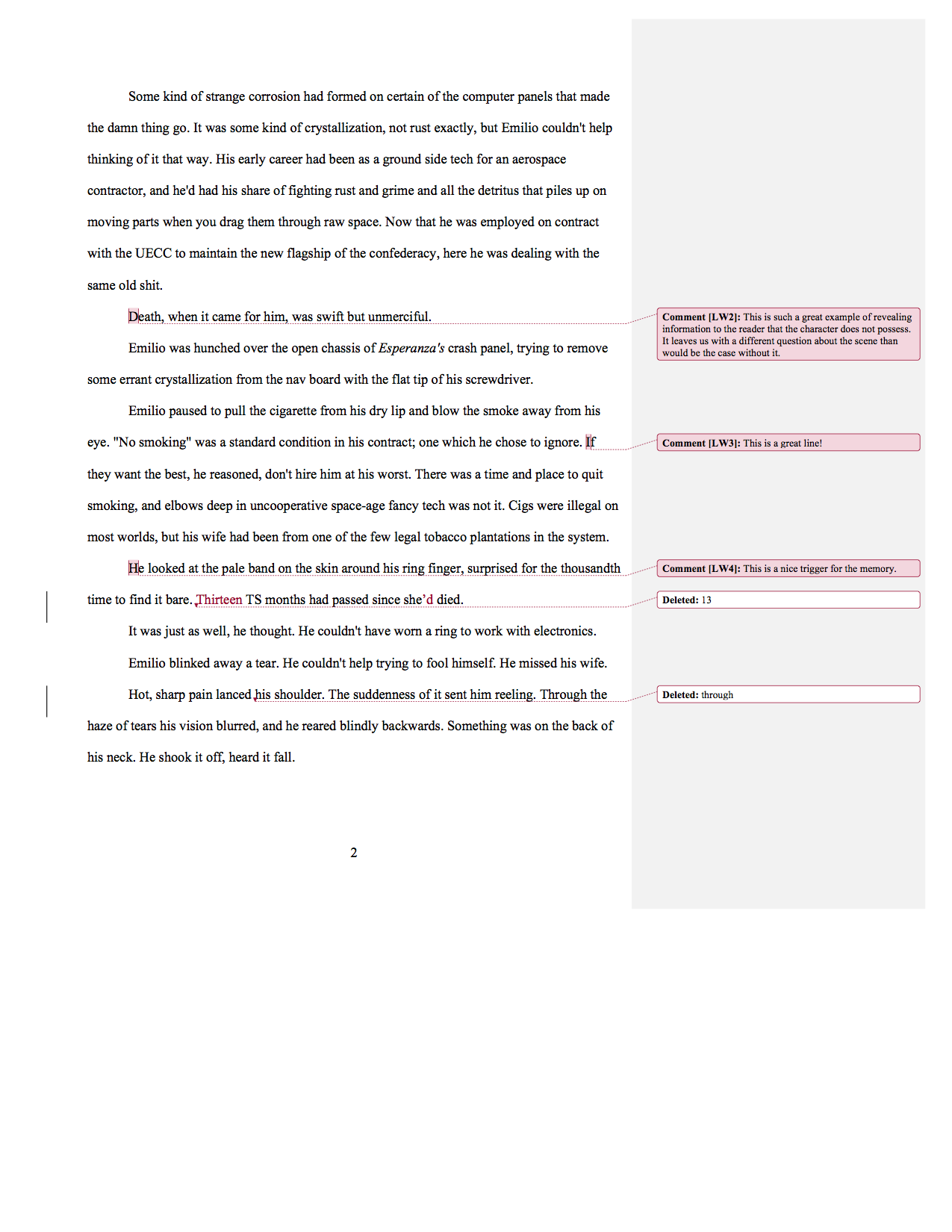

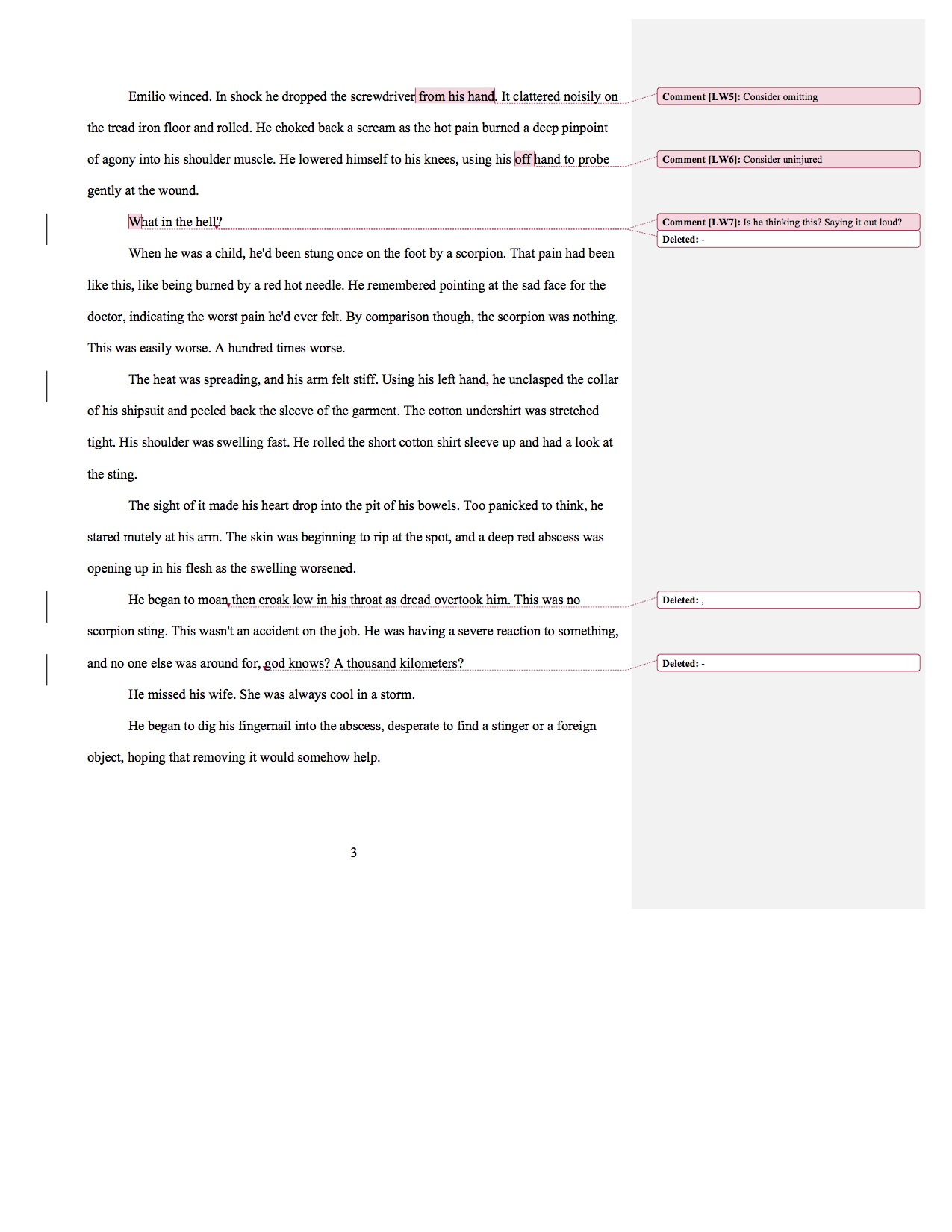

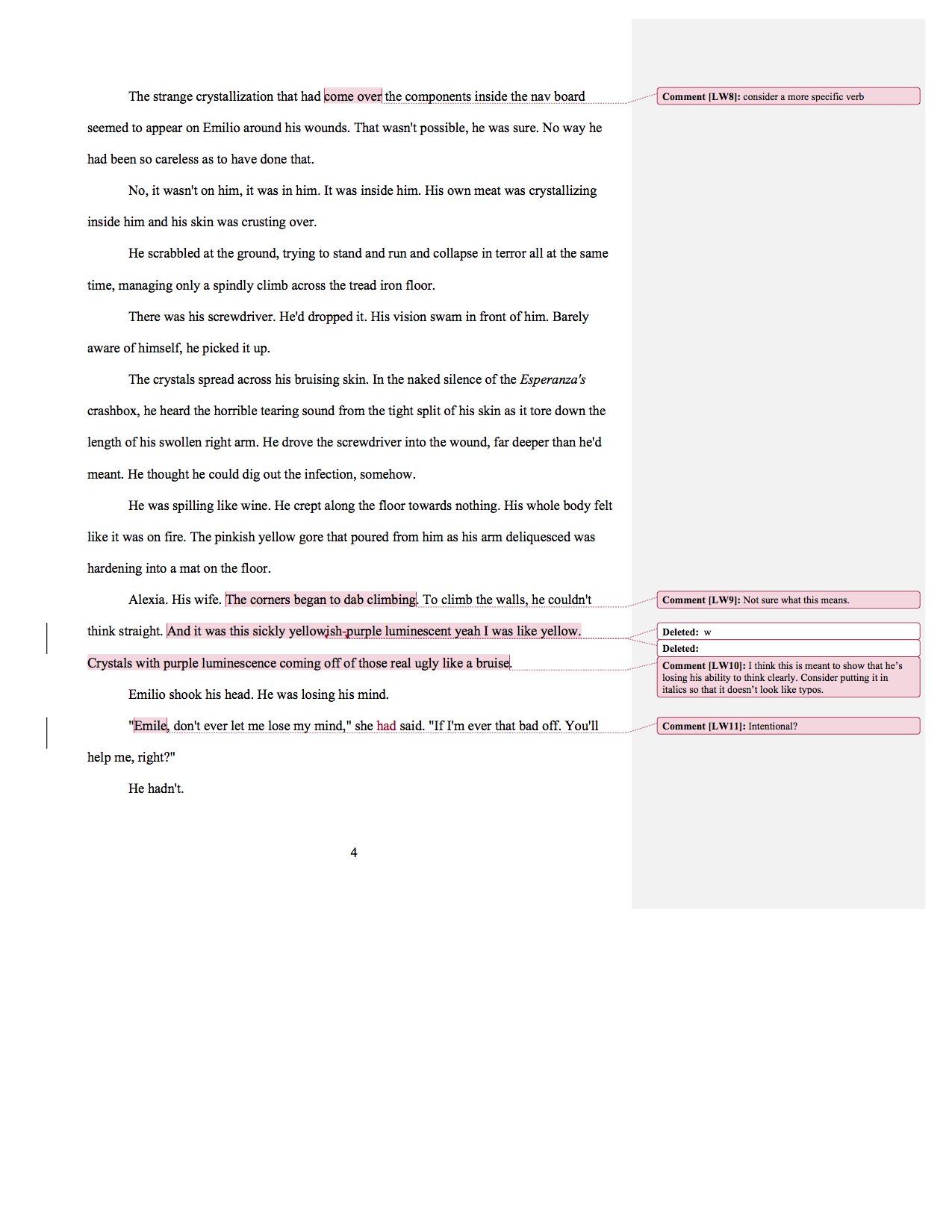

In this episode, fiction editors Leslie Watts and Anne Hawley critique the first chapter of Esperanza, a science fiction horror novel by Mike Ward. They discuss narrative drive.

Different people use the term “narrative drive” to mean different things. What we discuss here is the amount of information the reader possesses relative to the character. The reader can have more, less, or the same information the characters in the scene have.

In the opening scene of our submission today, the author gives the reader a key piece of information that the character doesn’t have, and it changes the way we experience the scene and the question that compels us to find out what happens next.

Listen to the Writership Podcast

This week's submission contains mild language and a gory injury.

ABOUT OUR GUEST HOST

Clark is away for a couple of weeks, but our friend and fellow editor, Anne, has graciously agreed to jump in and help out. You may remember Anne from episode 106.

After a career in public service during which she wrote fiction to stay sane, Anne Hawley has turned her talents to writing professionally.

As a founding member of the Super Hardcore Editing Group and a graduate of Shawn Coyne’s Story Grid Workshop, she writes and edits from her small house in Portland, Oregon. When she leaves the house it’s usually on her Dutch bike, Eleanor.

Her forthcoming novel, Restraint, is a sweeping historical love story about a gifted and sexually repressed artist in Regency London. Under the dangerous gaze of high society, he must deny his attraction to the young nobleman who has hired him to paint his portrait, or else risk his livelihood and his reputation by giving in to his secret desires. It's Pride and Prejudice meets Brokeback Mountain in a bittersweet story of two men who fall in love in a time and place where homosexuality is still a capital offense.

Wise Words on Narrative Drive

“Narrative drive is that quality that keeps readers riveted. It is the lightening in a bottle that creates great fortunes. If your work has none … fuhgetaboutit.”

Editorial Mission—Check for Narrative Drive

Take a slow scene in your story, and look for places where you can reveal more, less, the same information as the character to pull the reader forward. Get feedback from beta readers or notice yourself that a scene is slow, not pulling the reader forward.

Editing Advice to Our Author

Dear Mike,

Thank you for your submission. Anne and I both appreciated the way you opened your story. You've done a great job of setting up reader expectations for a horror story. It’s clear right away that we aren’t in a thriller or plain action story because of the circumstances of Emilio’s death—they certainly qualify as horrifying—and his final cogent thoughts are of failing his beloved wife, which for him seems like a fate worse than death.

One of the things we most appreciated about the story was your use of narrative drive. People sometimes use the term to describe different things, but what we mean is what the reader knows relative to what the POV character(s) know. We have three options in this respect: the reader can know less than (mystery), the same as (suspense), or more than (dramatic irony) the POV character in a scene (We’ve used the terms that editor Shawn Coyne uses, but other people describe them with different terms). Authors tend to employ mystery and suspense more often than dramatic irony, so it was exciting to see it employed to great effect in your opening.

Why does this matter so much? One of the reasons a reader continues to read a story is to answer a question raised by the events of the story. The narrative drive technique affects the question(s) the reader asks and therefore the answer(s) they seek.

When you said, “Death, when it came for him, was swift but unmerciful,” you let us know that the question is not if Emilio will die, but when and under what circumstances, and perhaps even why. We might also wonder how unmerciful it will be and how Emilio will meet his death. It’s a completely different inquiry and as readers, we view what happens and the information revealed in a different light and have a different emotional reaction when he dies. This question compels us to keep reading through end of the scene.

We also know that this horrifying spider has laid eggs in the ship thought to be the United Earth Confederate Colonies’ last hope. This question compels us to read further.

The other types of narrative drive are operating in this scene as well. Mysteries include Emilio’s understanding of the political climate and who the major players are. He also knows what happened to his wife and how she lost her mind. As for suspense, we know about the sting as it comes and its effect on Emilio when he does. But the big questions that will cause us to turn the page are most likely those that come as a result of what we know that he does not.

Thanks again for your submission!

All the best,

Leslie

Line Edits for Our Sci-Fi Horror Story

Image courtesy of egal/bigstockphoto.com.

Ep. 107: Check the Tension in Your Opening Scene

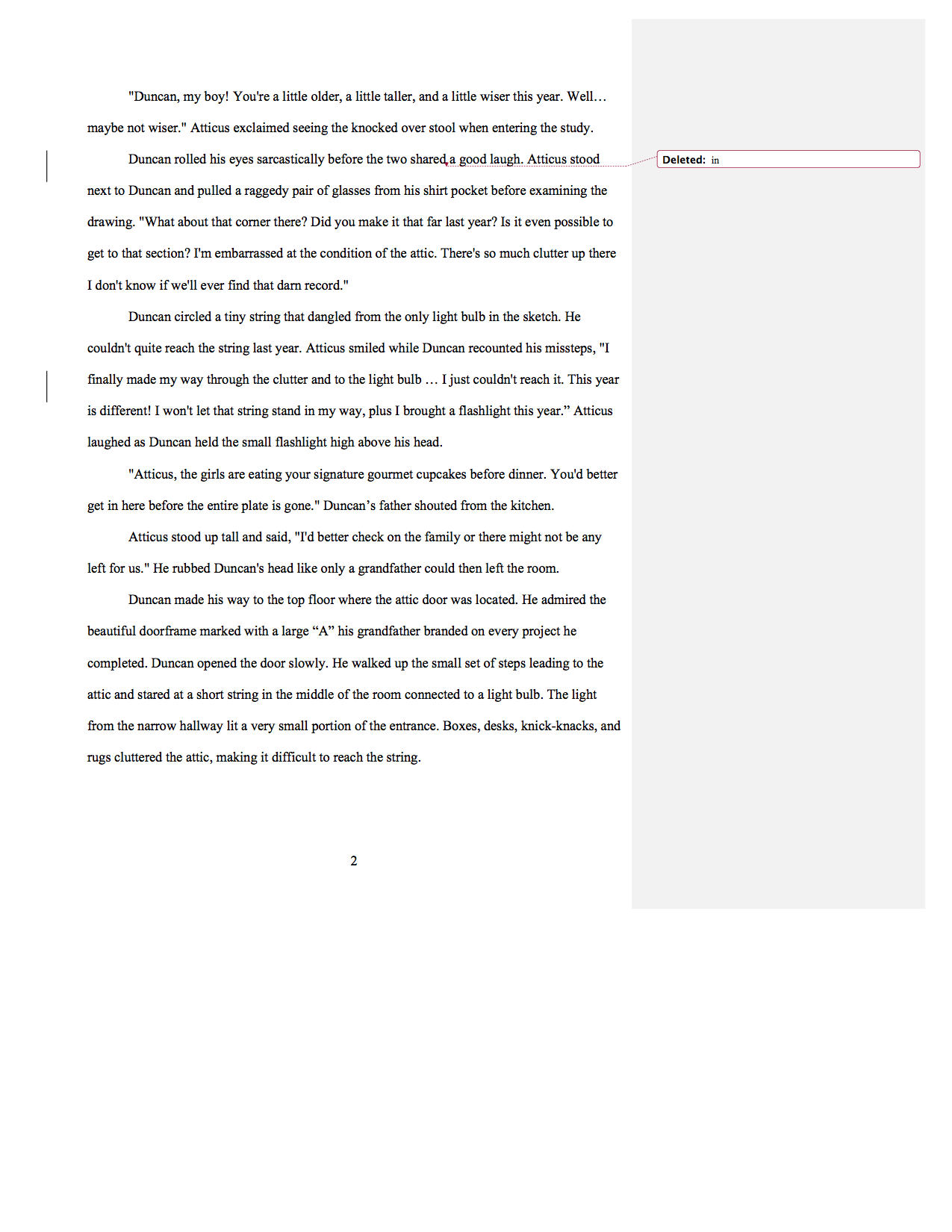

In this episode, fiction editors Leslie and Valerie critique the first chapter of The Arctic Compass, a middle grade fantasy novel by Ryan Gannon. They discuss how to check your opening scene for tension.

Listen to the Writership Podcast

About Our Guest Host

Clark is away for a couple of weeks, but our friend and fellow editor, Valerie, has graciously agreed to jump in and help out. You may remember Valerie from episode 105.

Valerie Francis is a best-selling indie author, story editor, and creative entrepreneur. After 20+ years in various writing-related careers, she published her first novel (a middle grade fantasy) in 2015. Upon hearing that J.K. Rowling sold 1,500 books her first year, Valerie set out to match that sales goal and, as a complete novice to the industry, hit her target in eight months. Her children's and women's fiction novels currently sell in over 10 countries.

Valerie's helps elementary schools foster a love of reading in their students, and she works with authors to develop their novels.

Valerie named her company Fifth Hammer Books, a reference to the myth of Pythagoras and the blacksmith's shop, because she believes that the most beautiful art is made, and the most important work is done, when the rules aren't followed. The Fifth Hammer is a reminder that the best ideas, like the best stories, work precisely because there is tension.

Learn more about Valerie and how she adds dissonance here.

Wise Words on Narrative Tension

“Narrative tension is often described as “the reason you turn the page”—in other words, the reader’s desire to know what happens next.

Narrative tension has three components: anticipation, uncertainty, and investment. … [T]here are different ways to create each component, and the way you mix them together will determine the flavour of the narrative tension in your book. Think of it like a stew: stew always contains a liquid base, solid ingredients, and seasonings, but your choices as the cook determine whether it’s an Irish Stew or a Cajun Gumbo.

Narrative tension should not be confused with conflict. Conflict is when characters are placed in opposition with other characters or with their circumstances. Conflict on its own does not guarantee narrative tension, and narrative tension doesn’t always come from conflict.

Narrative tension should also not be confused with pacing, which is the speed at which you tell the story. A fast or slow pace can support tension, but pacing alone doesn’t create tension.”

Mentioned in the Show

Here is a great post on narrative tension.

Here is another one!

Editorial Mission—Check for Tension

Tension is the vehicle that pulls your reader through the story. When people talk about tension, they often mention conflict, stakes, and pacing. These are all important and related to tension, but how do you create it, what are the elements? As Saul Bottcher mentions in the quote for the episode, it’s composed of anticipation, uncertainty, and investment.

This week, we want you to check your story’s opening for tension.

- Have you set up the possibility that something interesting is going to happen?

- Have you left room for uncertainty? Is there an open question in the reader’s mind?

- Have you added reasons for the reader to care about what happens?

If you’re lacking any of these elements in your opening scene, be sure to augment them.

Editing Advice to Our Author

Dear Ryan,

Thank you so much for your submission. This is such a delightful premise for a story, one that young readers would really enjoy. The attic is a great setting in this scene, and the Rube Goldberg-like action is really fun. Valerie and I have some suggestions that we think could take the lovely elements you already have and make them even stronger.

One important point that Valerie shared as a middle grade author is that a book’s competition (particularly for young readers) is not another book. It’s all the devices. There is no difference between writing for an adult, teen, tween, or kid when it comes to the elements of a great story and getting the reader to turn the page.

Tension is vital in pulling your reader into the story right away. It can be tricky to develop, though, so I want to unpack it a bit. Tension is created when the character has a specific goal, we care about whether he attains it, and a question arises in our minds about whether he will be successful.

You can help the reader care about your character and whether he’s successful in several ways, and it helps to add layers of interest and empathy. The character can be likeable or similar to the reader or someone they know, but that isn’t the only way. The challenge the character faces could be like one we face, or we might simply be curious about how someone like the character will work out a complex and challenging problem. One of the best ways to make the reader care about whether the character is successful is to show us what he wants and why he wants it—very specifically. We all have desires, so we understand the feeling of wanting something badly. The object of the character’s desire could be something we wouldn’t ever pursue. What we relate to is the wanting, and a specific desire is more powerful.

Along those lines, we want to know what’s at stake for the character if he fails. It would certainly be tragic if the magic of Christmas were lost forever—that’s pretty universal for kids who celebrate the holiday, and that’s a great place to start. But when we have desires or stakes that are common, we can miss out on details that make them more compelling. Knowing what failure means to the specific character in specific circumstances helps us to relate more easily. Consider Charlie and the Chocolate Factory and what failing to attain the golden ticket would have meant to Veruca Salt compared to Charlie. This doesn’t mean that we don’t care about Veruca or people whose lives are easier, but a story about her would be more compelling if she risked losing something that meant a lot to her. The same negative consequences have different meaning and impact for different people, and that difference affects how the reader relates to and cares about the character’s efforts to achieve the goal.

Another aspect of tension is anticipation. When the character achieves his goals easily, the reader doesn’t have time to wonder or worry about whether the character will achieve the goal because it happens so fast. Stretching out the anticipation with obstacles and missteps will increase the tension so that your reader can’t help but keep reading.

If we put these elements together, Duncan is a likeable kid, but I suspect you could reveal more about him and his desire than we’ve seen. This is not to say you need to add loads of new material or present it in an obvious way, but it would be interesting to see more of what makes Duncan different from other boys in his world and what makes him care so much about finding Santa. What does he lose if Santa is lost forever?

Consider making the obstacles tougher for Duncan and making him stretch and work for what he wants. Middle grade readers have a lot going on because they aren’t little kids receiving the care and attention that their younger peers do, but they don’t have the autonomy of their older peers. Things are changing rapidly mentally, emotionally, and physically. And everything feels hard. A character who faces seemingly insurmountable challenges will naturally appeal to readers of this age, and they will want to keep reading to find out what happens to him.

Thanks again for sharing your magical story with us!

All the best,

Leslie

Line Edits for Our Middle Grade Story

Image courtesy of Aaron Amat/bigstockphoto.com.

Ep. 106: Capture Your Character’s Essence

In this episode, fiction editor Leslie Watts and guest fiction editor Anne Hawley critique the opening pages of The Bad Shepherd, a published crime story novel set in Los Angeles in the 1980s by Dale M. Nelson. They discuss characters, how to make them relatable, and how to make sure you’ve captured their essence in your story.

Listen to the Writership Podcast

This week's submission contains colorful language and drug use.

About Our Guest Host

Clark is away for a couple of weeks, but our friend and fellow editor, Anne, has graciously agreed to jump in and help out.

After a career in public service during which she wrote fiction to stay sane, Anne Hawley has turned her talents to writing professionally.

As a founding member of the Super Hardcore Editing Group and a graduate of Shawn Coyne’s Story Grid Workshop, she writes and edits from her small house in Portland, Oregon. When she leaves the house it’s usually on her Dutch bike, Eleanor.

Her forthcoming novel, Restraint, is a sweeping historical love story about a gifted and sexually repressed artist in Regency London. Under the dangerous gaze of high society, he must deny his attraction to the young nobleman who has hired him to paint his portrait, or else risk his livelihood and his reputation by giving in to his secret desires. It's Pride and Prejudice meets Brokeback Mountain in a bittersweet story of two men who fall in love in a time and place where homosexuality is still a capital offense.

Wise Words on Characters

“Story is as much (if not more) about characters as about plot. They are your plot—their needs, wishes developments. Their introduction and establishment should be foremost on your mind. Even if you begin with heavy plot action, character introduction should be integral to this action, and the action of the plot should not be just for its own sake, but should serve to further growth of the participating characters.”

Mentioned in the Episode

The Bad Shepherd is available to buy here.

If you love podcasts like we do, you might enjoy a new one from C. Steven Manley, called the Story Shots podcast. Manley is a longtime storyteller and the author of the Paragons trilogy and Brace Cordova space opera series. The episodes are short (thus shots) and full of insights and practical tips. You can find the Story Shots podcast on Apple podcasts and Stitcher.

Editorial Mission—Capture Your Character’s Essence in a Sentence

Write a one-sentence description of each character that includes their name, who they are in the story (could be their position or status), and something of what makes them unique and also hints at what they want or need. You could start with this [Name] is a [status, position] who [does, thinks, believes something]. Try to limit each sentence to twenty-five words. Here are two examples:

Elizabeth Bennet is a marriageable, middle class woman with no fortune, who thinks wealthy people are prideful, and will marry only for love.

Charlotte Lucas is a middle class spinster who prefers to marry a ridiculous man she doesn’t respect than be a burden on her family.

Use this sentence as a jumping off point for introducing your character by showing who they are through action, dialogue, description, or reactions.

Editing Advice to Our Author

Dear Dale,

Thank you so much for your submission. Anne and I really enjoyed your opening! You did a great job of conveying the hardboiled/noir aspect of the story and dropped it into LA in the early 1980s. There are lovely parallels in terms of crime, drugs, and music. You’ve shared some incredible concrete details in this opening that make for a rich setting for the story. The Plymouth Fury, club names, and the clothing all come to mind.

I had some trouble with Bo Fochs as the protagonist and POV character in this first scene because we get one action (he’s looking through the viewfinder of a telephoto lens at his informant) and one internal thought (Good, you’re smart to be scared, Rik.) before we read a page of backstory about Rik Ellis is and why he’s sitting in a café across the street from our protagonist and POV character. This information is relevant to the scene (though it might be more powerful to withhold it and leave some mystery about what’s going on), but we don’t have an opportunity to know who Bo is.

We find out why Rik is sitting in the café, his motives (at least insofar as Bo knows them), and what he has at stake. We don’t have this for Bo, however. We don't know what he looks like, which may not be the most important thing (and some authors purposefully let the reader fill in the blanks), but if he engages in story action in the future (fighting, chasing, etc.), it would be good to have an idea of how he would do (we find out, for example, that Gaffney is fit and fast). You’ve revealed some reaction after the backstory, but still not enough that for me to have a sense of who Bo is so we’re ready to jump in the Plymouth Fury with him and join him on his adventures.

It’s important to note, though, that Anne wasn’t bothered by this, so when considering this, you would want to tap into your sense of the story and where it goes from here.

Of course, you want to allow for some mystery about who Bo is; you wouldn't want to share everything we’ll ever need and want to know about Bo right here, but consider what does the reader need to know to relate to him (some challenge, emotion, situation that your ideal reader can relate to) and care about whether he’s successful in his scene/story goal (what he wants/needs, what’s at stake if he’s not successful).

On a somewhat related note, we’re getting Bo’s direct thoughts, and we seem to be in third person limited POV, rather than omniscient. It seemed unlikely that while he’s doing the stakeout that he would be (necessarily) thinking about all the elements of the backstory include—absent a compelling trigger in the present. Consider what would he naturally be thinking about as the scene is unfolding before him.

Thanks again for sharing your opening with us. It was a fun trip to another time and place!

All the best,

Leslie

Line Edits for Our Crime Story

Image courtesy of Demian/bigstockphoto.com.

Ep. 105: Do Your Scenes Work?

In this episode, I'm joined by best-selling author and fiction editor Valerie Francis while Clark is away. We critique the prologue of Shadow Falls, a thriller novel by Maxwell Perkins. Scenes are the building blocks of your story, but how do you know if an individual scene works? Valerie and I use Shawn Coyne's Story Grid analysis to look at what's working in this opening scene and how the author might make it stronger.

We have a special treat for you. The author is a professional audiobook narrator, and agreed to share a reading of his submission with us. We weren't able to include it in the podcast episode that aired, but we've included it here in the show notes. We're considering having professional narrators read the submissions in future episodes. If you have a moment, please let us know in the comments or at hello@writership.com if this sounds like a good addition to the podcast.

Listen to the Writership Podcast

Wise Words on scenes

“There is just no hiding for a writer when it comes to a scene. It either works or it doesn’t. There is either a very clear shift in value from beginning to end—a change—or there isn’t. If there is no change, no value at stake, no movement, the scene doesn’t work. And if the writer’s scene doesn’t work, no matter how well he can craft a sentence, his Story won’t work.

”

Mentioned in the Episode

You can find the video about Ian Rankin's writing process here.

You can find Shawn Coyne's original post on the Five Commandments of Storytelling here, and this is an episode of the Story Grid Podcast in which he takes a deeper dive into these topics.

Want to learn more about Valerie? You can find her here.

Editorial Mission—Check Your Scenes

Review a scene in your story to discover whether it's working, and why or why not, by unpacking the six elements of a successful scene (You can see our analysis of the submission in the letter to the author below):

- Inciting incident: an action or coincidence that throws the main character in the scene off balance

- Progressive complications: the obstacles that get in the way of your main character's scene goal

- Turning point: an action or revelation that brings the main character to a point of no return

- Crisis question: having reached a point of no return, the character faces a choice of the best or two bad choices or two irreconcilable good choices

- Climax: the main character's choice

- Resolution: what happens as a result.

If you find something that’s missing or that could be made stronger, add it to your list of items you need to fix (rather than trying to fix it right away).

Editing Advice to Our Author

Dear Maxwell,

Thanks so much for your submission! Valerie and I both enjoyed reading your prologue and getting to know your characters and found that this scene had us fondly remembering Stand by Me.

I’m concerned after the fact that this may not be as helpful to you as we’d like it to be in light of the fact that the characters don’t appear again in the book and that we’re seeing this scene out of context more so than we normally do for a submission. I hope some of this discussion will be useful to you, though, if not with this scene than with others.

We looked at the scene through the Story Grid (SG) filter, and it’s certainly not the only way to assess a scene, but it’s one we’re both familiar with and that we’ve found helpful. I can’t speak for Valerie, but for my part this framework provides specific and actionable feedback that’s better than a vague sense of something’s not quite right here. Shawn Coyne developed this tool out of necessity. He needed a way to show authors how to fix their stories so that they could become best sellers because acquiring a certain number of successful books every year was a requirement of employment. But it also makes sense to me in light of what I know about story and where stories come from and why we tell them. I could go on about that, but this is meant to be a written critique of your scene. I could see how this might feel like unwarranted criticism, though, so I wanted to explain this.

I want to make it clear that in our assessment we don’t speak for Shawn Coyne, and this isn’t an official SG pronouncement. With these caveats, we present one way you could look at the scene using this framework.

The Story Grid has five commandments of story and one “little buddy”:

- Inciting incident: something happens that throws the character or world out of balance.

- Progressive complications: escalating degrees of conflict related to what the main character in the scene wants (sometimes to regain the status quo, sometimes something else).

- Turning point (little buddy of the second commandment): a point where someone acts or information is revealed that forces the character to make a decision.

- Crisis: the dilemma that the character faces that can be distilled this way: the best bad choice (like the lesser of two evils) or irreconcilable goods (two positive but mutually exclusive options).

- Climax: the moment when the character acts based on his decision.

- Resolution: shows the world after the character has made his choice.

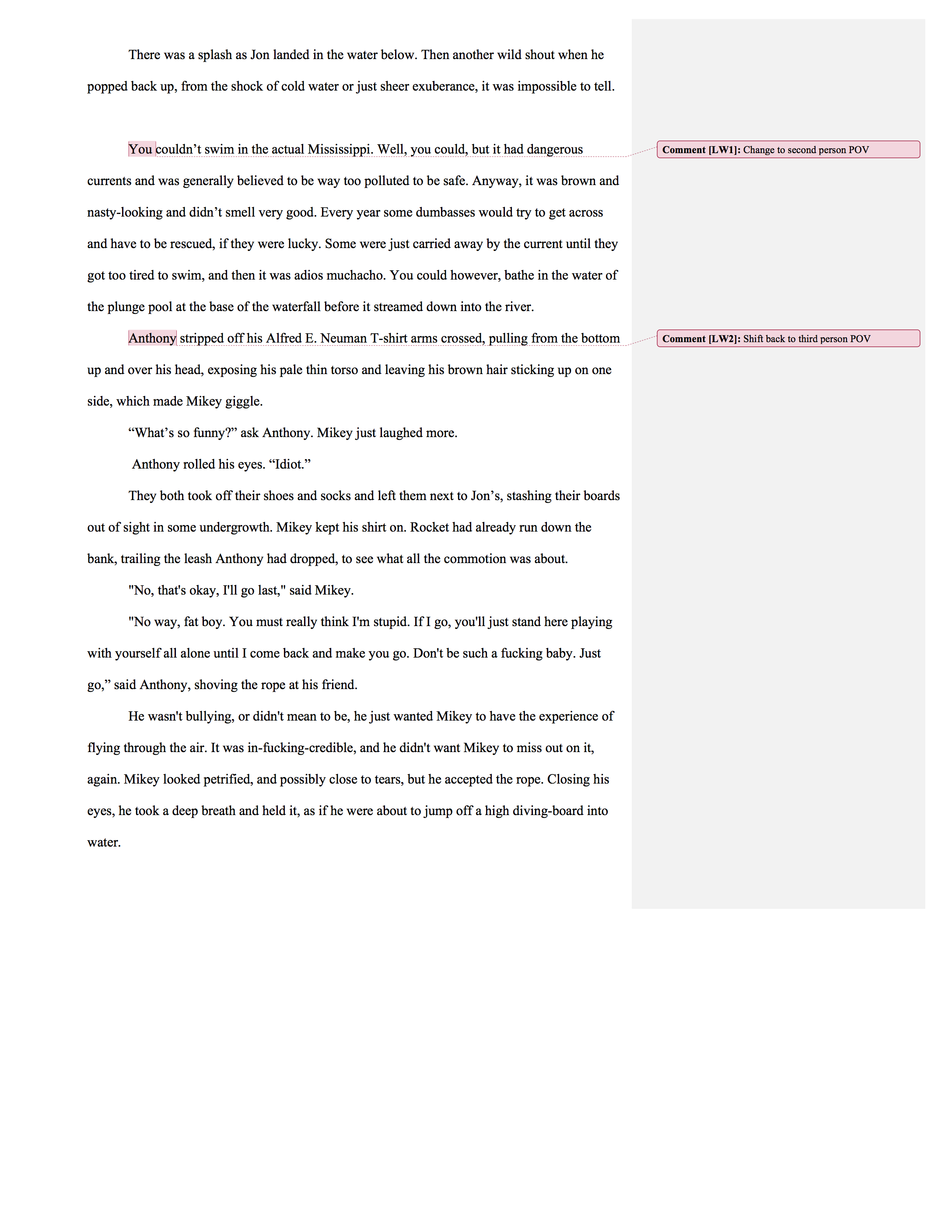

If we look use this framework in the scene before us, we could break it down this way:

- Inciting incident: Mikey decides at long last that he will jump.

- Progressive complications: Depends on who the main character in the scene is. Anthony wants Mikey to jump. It’s not altogether clear what Mikey wants because he says he will jump, but then seems to have second thoughts. Our discussion on this point is pretty speculative.

- Turning point: This is another point where we’re not clear. Again, it depends on who the main character is in the scene. We get a closer view of Anthony, so let’s assume it’s him first. He wants Mikey to jump, and Mikey is stalling. If Mikey decides he’s not going to go, then we might have a turning point that requires some action on Anthony’s part to get what he wants, but Mikey never says he won’t. If we look at Mikey as the main character in the scene, there is no turning point for him unless, for example, he learns that there is a dead body in the water below.

- Crisis: This is a little confusing because we’re still left with the question of will Mikey jump or won’t he. Anthony doesn’t make the decision, and Mikey doesn't face a clear best-of-bad or irreconcilable-goods question (as far as we know because we’re not aware of what he’s thinking and feeling). Is he worried that Anthony would never speak to him again, for example? We don’t know what the consequences might be if he decides not to jump.

- Climax: Mikey decides to jump.

- Resolution: Mikey jumps. Jon has discovered a body in the water, which causes Mikey to vomit. This is where we would argue that the scene turns, but the conflict about Mikey jumping in the water has already been resolved, so this turn didn’t impact his decision.

Although I feel confident of this analysis of the scene, it doesn’t mean you have to agree with it. It’s your story, no one knows it like you do, and I’m well aware that I could have missed something. I also think that all the elements are here for a scene that works under this construct, that you could shift the discovery of the body, but you should do what feels right to you.

The analysis that I feel less confident about is whether this works as a prologue for your story because I don’t know what happens later to see how it fits in. My biggest concern, which we shared in the episode, is that the reader might wonder what happened to those kids from the prologue. Does that matter? It depends on what comes later. The only thing I would add after the fact is a consideration of Chekov’s gun, but again that could only be assessed in light of the whole story. If we had an omniscient POV showing the boys from a distance and revealing how sometimes things go wrong who saw the boys from a distance without our getting attached to them and noted how it could be dangerous (for the reasons cited), but that mostly this is a great place to swim, then that would appear to be more relevant to the overall story, but again, it’s hard to say without knowing where the story goes from here.

Thanks again for your submission, Maxwell! It presented a fun challenge for us!

All the best,

Leslie

This Week's Submission

Image courtesy of [CREDIT GOES HERE]/bigstockphoto.com.

Ep. 104: Revising Your Action Scenes

In this episode, Clark and I critique a scene from Beneath the Crypt, a middle grade fantasy novel by Alex Heath. We talk about how to evaluate and revise your action scenes. When characters fight, chase each other, or engage in acts of derring-do, it can be hard to keep track of all the moving parts. Often, the clear image of how the action unfolds in our minds doesn’t make it into the story. If you unpack what’s happening in your action scene, you can make sure that it does everything you intend, and nothing you don’t.

Listen to the Writership Podcast

Wise Words on Action Scenes

“However, Hollywood films are not good examples of action scenes for books. Action scenes in movies are eye candy, designed to give the viewer a visual “Wow!” at the awesome feats. But all these action scenes flash by in just a few seconds. The viewer doesn’t have time to even think about how impossible that stunt is. In a book, the reader is with that scene a lot longer. She has more opportunity to say, “Wait a minute. They can’t do that.” And the moment she does, you’ve lost her. ”

Additional Resources and Links

Want to find out what Henry did to upset the thief of Carcassone? Read on here.

Clark mentioned that the most realistic fight scene he’s observed is in Old Boy with Josh Brolin.

John Wick with Keanu Reeves is a movie with fight scenes that are realistic in how they portray the combatants’ energy.

To find great examples of dialogue in action scenes, check out Spider-Man comics.

Editorial Mission—Unpack Your Action Scenes

In episode 67, we asked you to look at model fight and other action scenes to help you revise your work. This week, we want you to unpack your own action scenes.

Use an action scene you’ve written and record what you observe in a list of what happens in the scene. Add every instance, one per line, of the following:

- action a character takes (e.g., character throws a punch)

- piece of information that’s revealed (e.g., character notices the bad guy has a knife)

- result or consequence (e.g., man falls to the ground)

Once you’ve exhausted everything you can think of about the scene, put the items in chronological order. Here’s an example:

- Fred slashed at Joe’s face with his knife.

- Joe ducked under Fred’s arm.

- Joe kicked the side of Fred’s right knee.

- Fred shouted.

- Fred fell to the ground.

- Fred dropped the knife.

- Joe grabbed Fred’s wrist with both hands.

- Joe twisted Fred’s wrist.

- Joe felt the bones crack.

- Joe felt relieved.

- Joe saw Fred’s friend walking toward him.

This is a simplistic list, but it will give you a clear view of what you have and what you need. When you're done, review the list and ask yourself these questions:

- Does it make sense?

- Have you missed any crucial actions, pieces of information, or results?

- Does each element appear in the best place in the sequence?

Next, consider the setting and where people and objects are, especially in relation to one another. I recommend drawing a diagram and using small tokens (I use Lego minifigures) to show keep track of people and objects, especially if you have a battle or an action/fight scene that involves more than two or three people.

Think about visibility. Is it a crowded street, the woods at night? What can your POV character actually observe (sights and sounds)? Does this affect the action as you’ve laid it out?

Once you’ve done all this, then revise your scene. You could approach this in different ways. You could use your new understanding of the scene to revise the one you’ve already written, write it from scratch, or begin weaving the sentences in the list together into a scene.

Why go through all this work? Action scenes are intense, fast-paced, and often contain several different elements. Sometimes the author has such a clear vision of the scene as a whole, as if it’s a video playing in their minds, that they don’t see and record the individual elements to transfer that conception to the reader’s mind. Unpacking what you’ve put on the page can help you discover if anything is missing.

Please remember this is a tool for revision! I wouldn’t mess with the minutiae while writing an early draft, but when you review it, if you deconstruct the action this way, you can be sure that what you imagine in your mind’s eye ends up in the story.

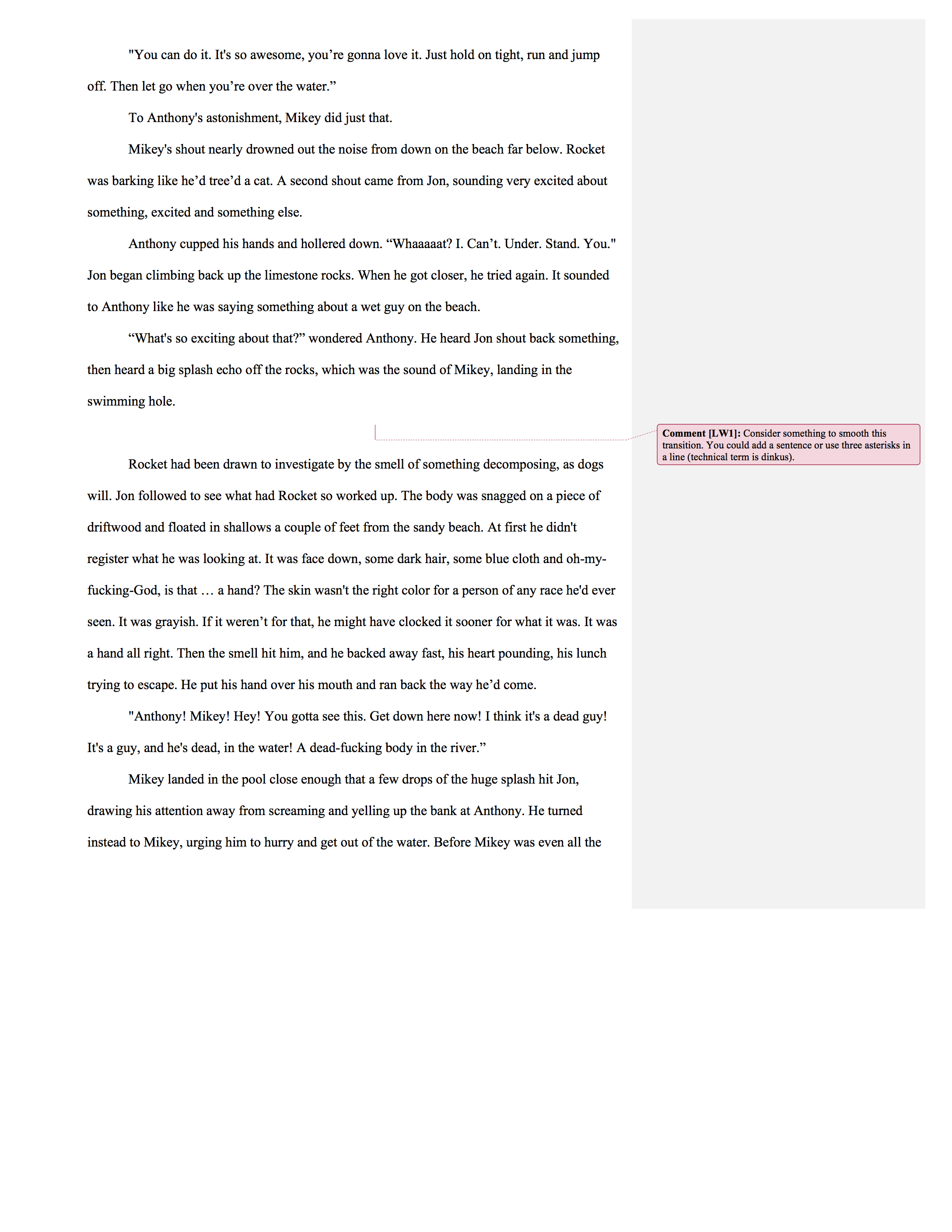

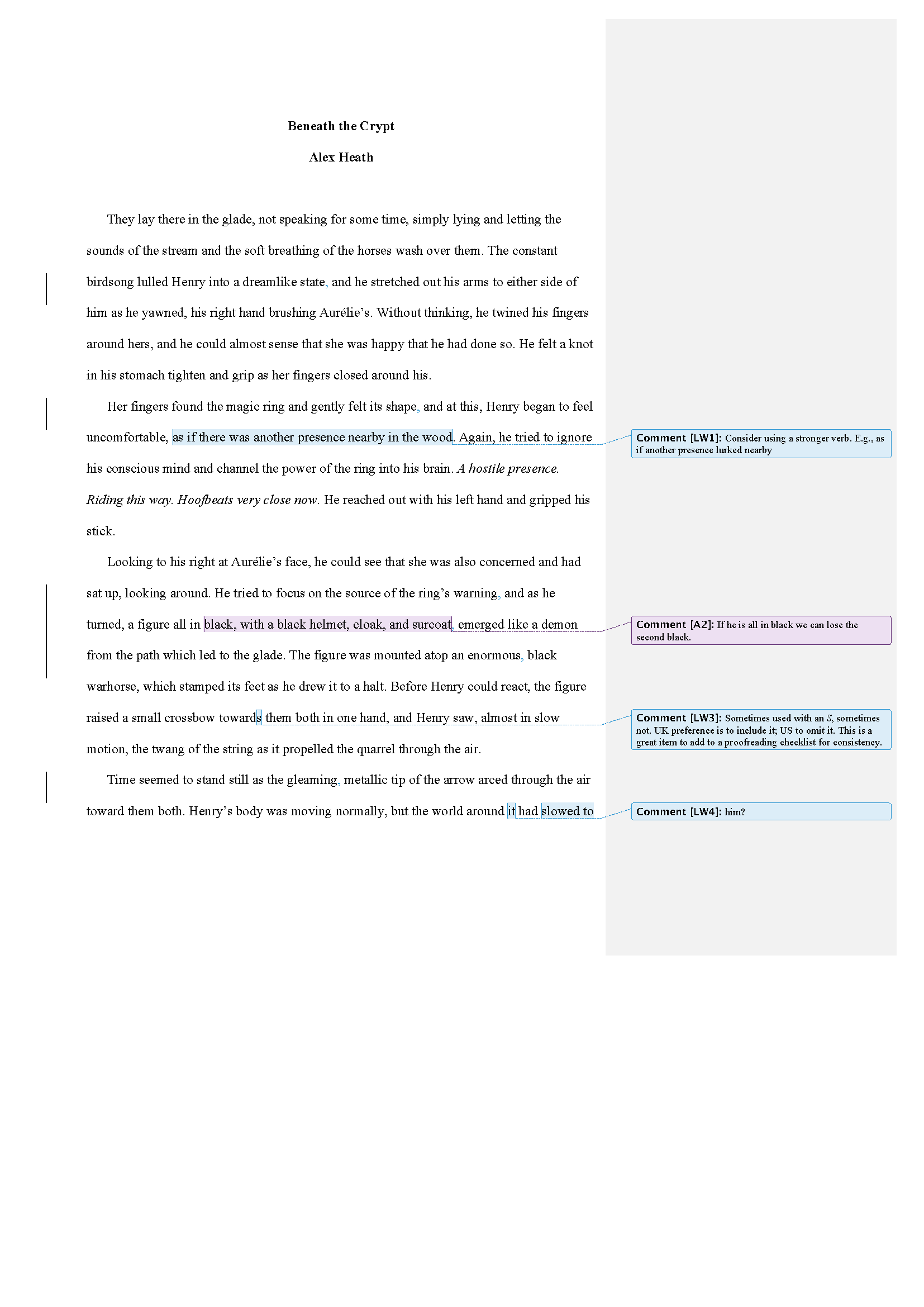

Editing Advice to Our Author

Dear Alex,

Thanks so much for your submission! Beneath the Crypt sounds like a fun adventure story, and Henry and Aurélie are great characters to play with. Even though we’re jumping into the middle of the story with no other introduction to the characters, it was easy to follow. The approach of the mysterious figure is a great hook to pull us into this scene, and the open question you leave us with at the end of the scene is intriguing and would make it hard to put the book down.

Clark and I focused on action scenes for this episode, and I think you’ve done a nice job of conveying who is doing what, where, and when, which as we mention in the episode can be a bit tricky. Although combatants in a fight don’t have time for a lot of reflection (unless one is skilled and facing an unworthy opponent), I think you could make the scene stronger with more reaction from Henry. I’d love to know about Henry’s experience in the fight, what he’s feeling physically and emotionally, and how he reacts what’s unfolding.

One example is when the thief faces Henry, and we get a pretty good look at the black-clad figure through Henry’s POV—with the exception of his face, of course. We see what he’s wearing, that the only armor he’s employed is a helmet, and that he is thin and lightly built (which could possibly clue the reader in to his identity or not depending on your intent and what you’ve revealed before this scene). We also see his weapon and that he is advancing on Henry with apparent violent intent. In the next paragraph, we see that Henry is scared and not sure what to do, but don’t know if he is generally scared or if something he’s seen and concluded about his opponent evoked the reaction. If you were to weave in a direct connection between his observations and what he does, the details you reveal would be immediately relevant to the scene before us rather than only the description of a character.

We noticed that you don’t have a lot of dialogue in the scene, and that may be in part due to what’s happening. As it opens, Henry and Aurélie are resting and wouldn’t necessarily be speaking. The thief is trying to avoid revealing is identity, so he might not want to speak if his voice is distinctive. Consider if there are opportunities when Henry or Aurélie might say a word or two periodically to break up the narrative and alter the pace.

We can’t assess this from only one scene, but wanted to mention this because it’s important in fantasy stories. The magic used in an action scene should be consistent with how magic is used in the story world in general. This is a helpful item to add to a revision checklist for anyone who writes speculative fiction.

For picky stuff, we flagged a few echoes and awkward phrasing in our comments. We spotted some places where specific verbs would enable you to cut some adverbs.

Note: We’ve labelled this middle grade fiction, but other factors within the story could tip it into young adult.

We appreciate your sharing this entertaining scene with us, Alex! Thanks again for trusting us with your words!

All the best,

Leslie & Clark

Line Edits for Our Mystery Story

Image courtesy of NejroN Phot/bigstockphoto.com.

Ep. 103: Narrative Identity and Why It Matters in Your Fiction

In this episode, Leslie and Clark critique “A Hero Least of All,” a literary short story by Tim LaFave. They discuss narrative identity and why it matters for your writing. As humans, we use story to make sense of our lives, and it’s important to understand the stories we tell about ourselves and the how this impacts our writing. We consider how being aware of our own narrative identity can help us revise, and we can use this emotional energy as fuel for our characters.

Listen to the Writership Podcast

Wise Words on Stories

“Stories are the way we make sense out of the events of our lives. Individually and collectively we tell stories in order to understand what has happened to us and to create meaning from those experiences. Storytelling is fundamental to all human cultures, and our shared stories create a connection to others that builds a sense of belonging to a particular community. The stories of a particular culture shape how its members perceive the world. In this way, stories both are created by us and shape who are. For these reasons, stories are central to both individual and collective human experience.

”

Additional Notes

Clark’s covers narrative identity in his course Punch Them in the Gut: Writing Fiction with Emotional Impact.

The two books on narrative identity that Clark mentioned are How Our Lives Become Stories, Making Selves and Living Autobiographically, How We Create Identity in Narrative by Paul John Eakin. Remember that Clark said these books are fairly technical.

We have a Patreon shout-out for E.A. Hennessy, the author of the steampunk novel Grigory's Gadget.

Editorial Mission—What's Your Story?

The more clearly we see and understand our own stories, the more we can use our emotions to fuel our stories, make our characters relatable, and connect with our readers. This week, look at your own life’s journey and where you’re at today. What stories do you tell yourself about your life and why you do what you do? Then consider one of the stories that you’ve written or are working on. Where do your stories show up? How can you bring more of your personal journey to make it more specific and connect with the reader?

Editing Advice to Our Author

Dear Tim,

Thanks for your submission to the podcast. “A Hero Least of All” gave us the opportunity to talk about narrative identity, a topic near and dear to our hearts. Like anyone else, writers mull over our concerns and worries, so they naturally find their way into our stories. It’s a great way to process events that are beyond our control and change the course of our own lives.

Michael is a great example of the way we can make sense of life because, given his circumstances, he could have been a very different person. Acknowledging that home isn’t what he would have wished for, but that the letters are his anchor in his present life demonstrates the way we use story to create a helpful narrative and cope with challenges. It’s not that he sees the world through rose-colored glasses, but he sees the world benevolently enough to keep him from falling into despair or lashing out.

You’ve done a great job helping readers empathize with Michael through the details you shared and the way he navigates a world that is not kind to him. We all know someone who is a bit awkward or sees the world differently, and I think your story helps people understand them better. This is one of the powerful things that stories can do—not only help us make sense of the world, but also to understand others’ experiences and worldviews. I found the story deeply touching, and I can't help but wish that the future holds something better for the Michaels of this world.

Just like any other story, the ones inspired by challenges we face need to work and avoid extra elements that don’t add to the telling. When you write for an audience beyond yourself, I recommend checking that everything included supports the story (the anecdotes, metaphors, descriptions). Not every aspect of what happens in real life will be relevant.

I also think this could be made stronger by showing us an episode or two from his hometown, the mail call episodes (before and after as contrast), and when he walks into camp after wandering around in the woods for three days. The third omniscient POV gives you lots of latitude to reveal powerful details to help the reader experience those scenes.

Generally speaking, when we use aspects of our personal stories in fiction, we need to make them worse or better than ordinary life in a memorable. Just as we wouldn’t include commonplace dialogue, make sure that the emotions and situations we include are larger than life. You’ve captured this well. For example, Michael doesn’t have one annoying nickname, he has many, some of which are humiliating and came to him through no fault of his own. He picks up new ones wherever he goes.

We did a light copyedit of the manuscript, and I’ve pointed out a few picky items in the submission. I suggest omitting scare quotes because they can become like speed bumps to the reader, and I made some other punctuation edits as well.

Thanks again for sharing your story with us and for trusting us with your words.

All the best,

Leslie & Clark

Line Edits for our Literary Fiction Short Story

Image courtesy of digitalista/bigstockphoto.com.

Ep. 102: How to Choose Your Story's Point of View

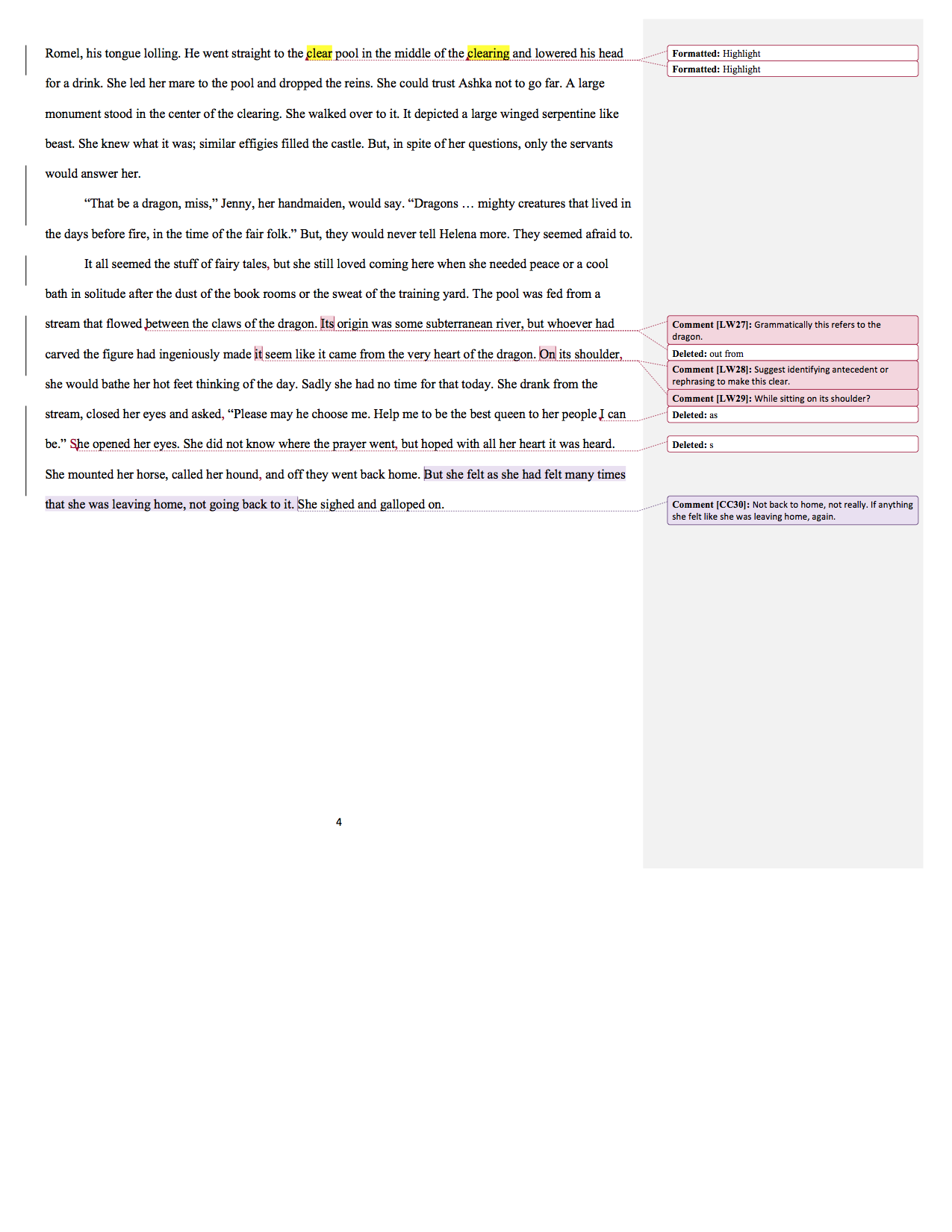

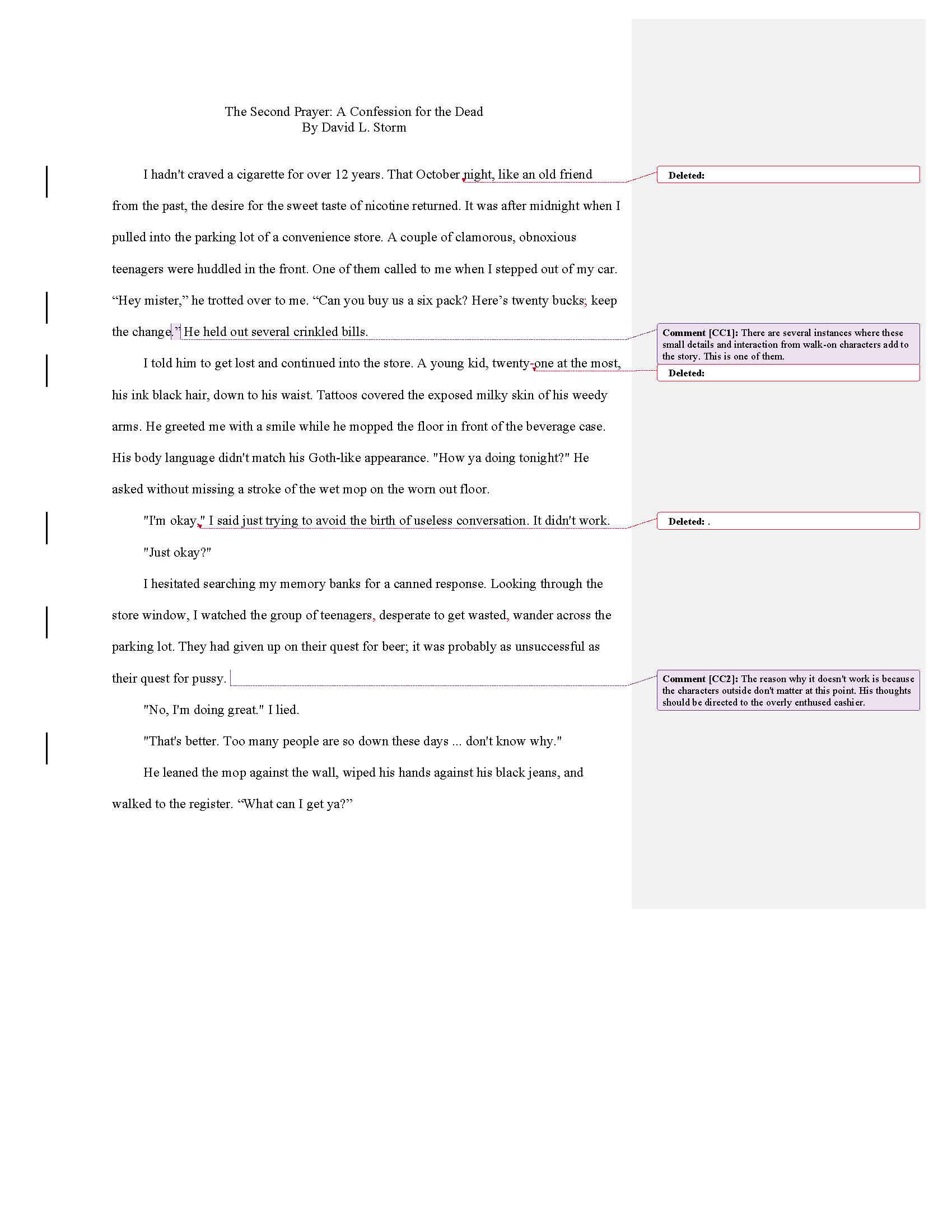

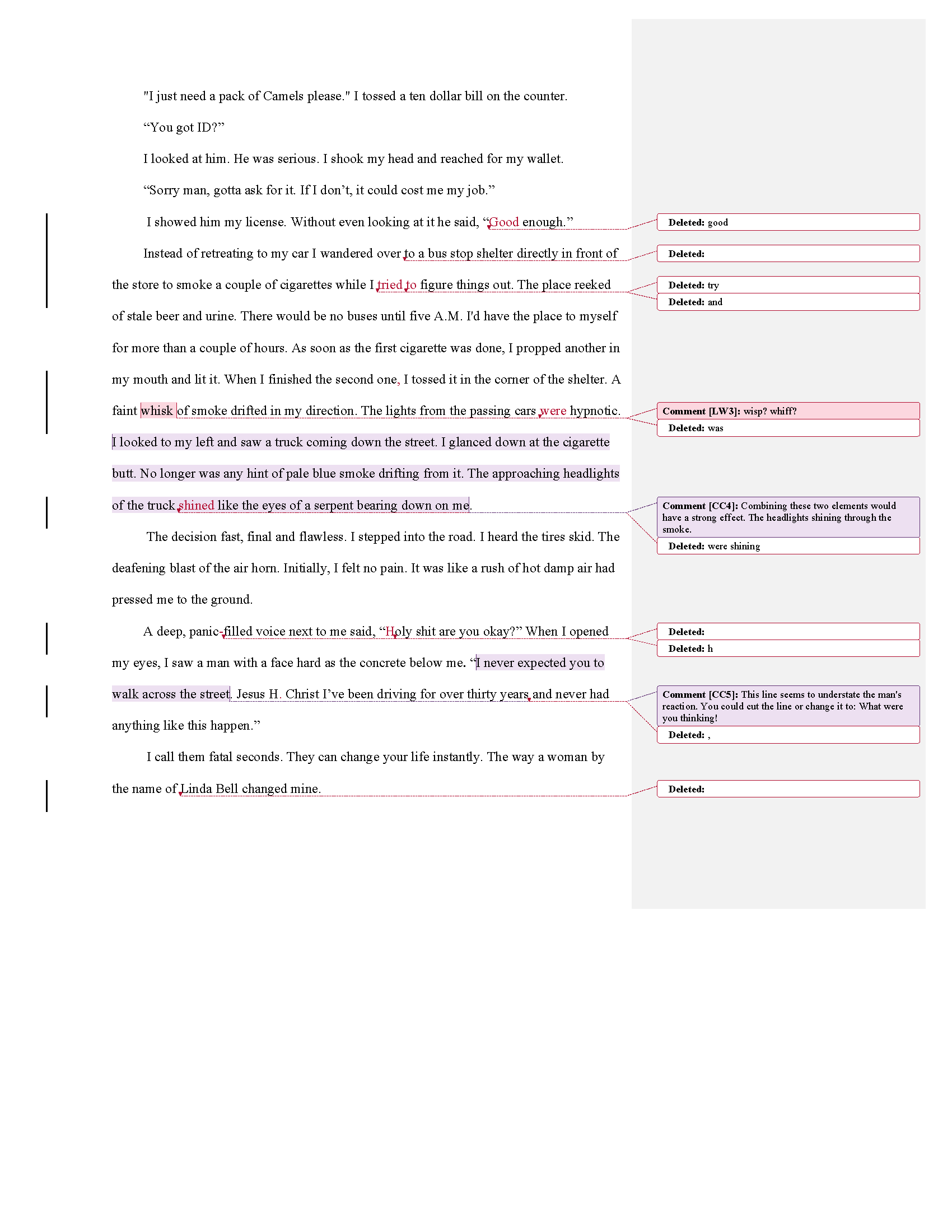

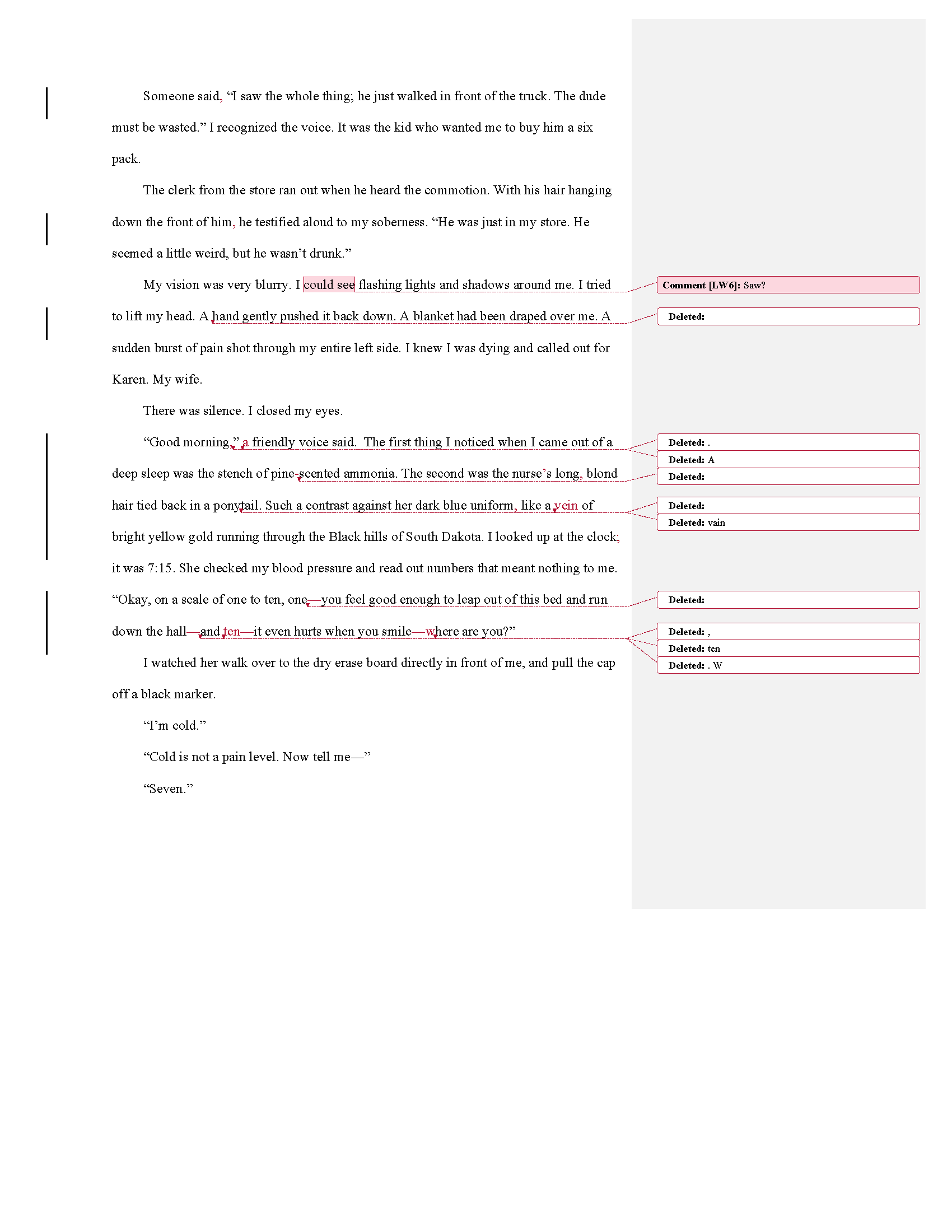

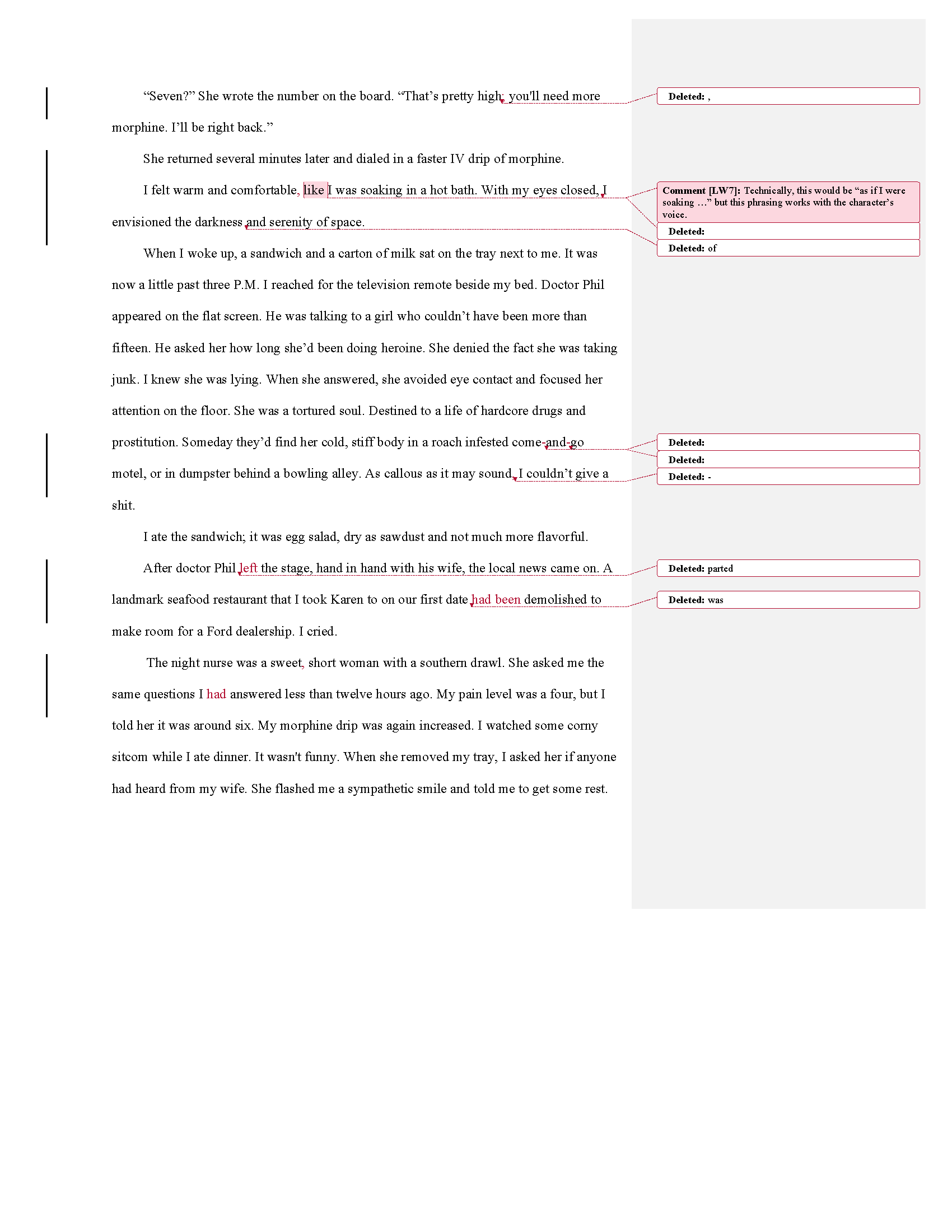

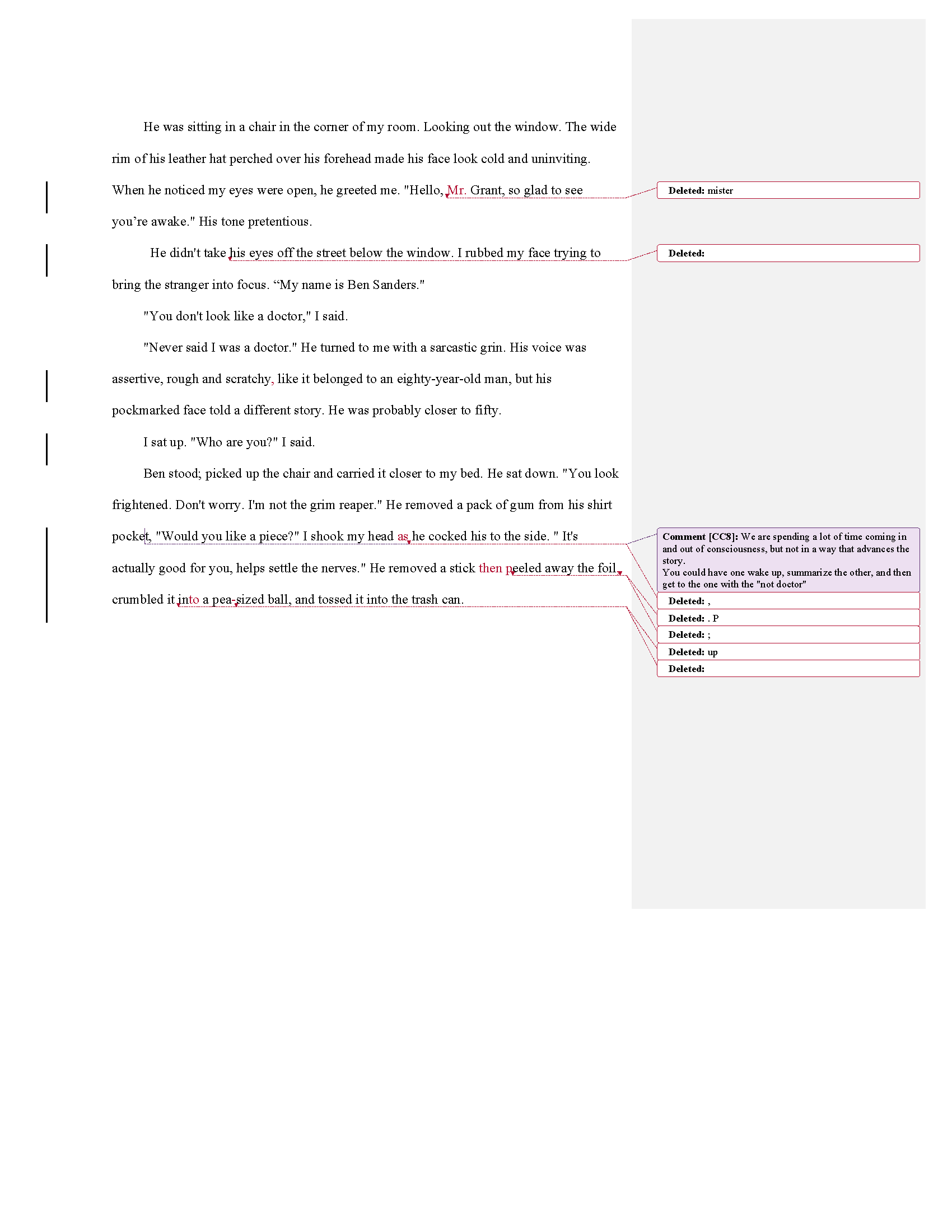

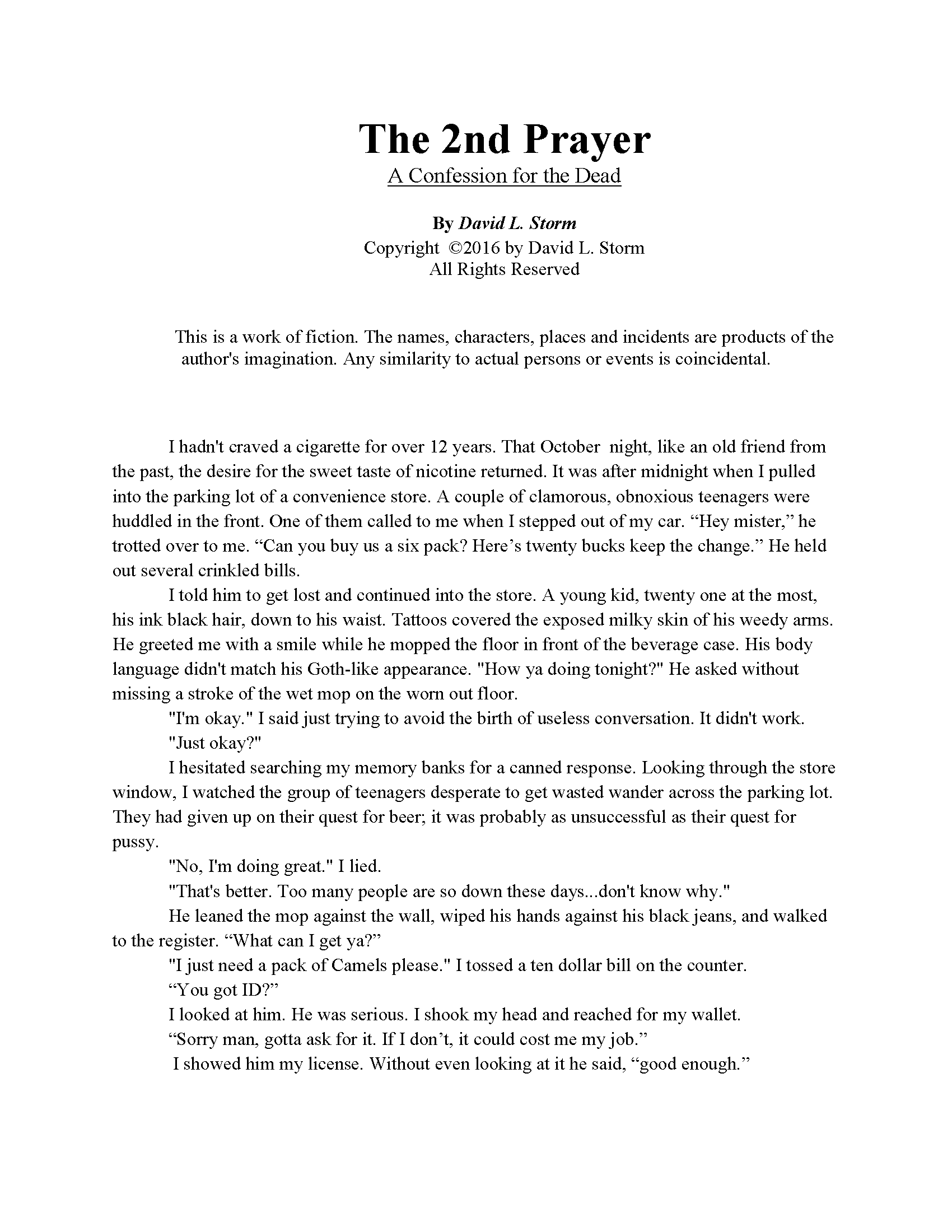

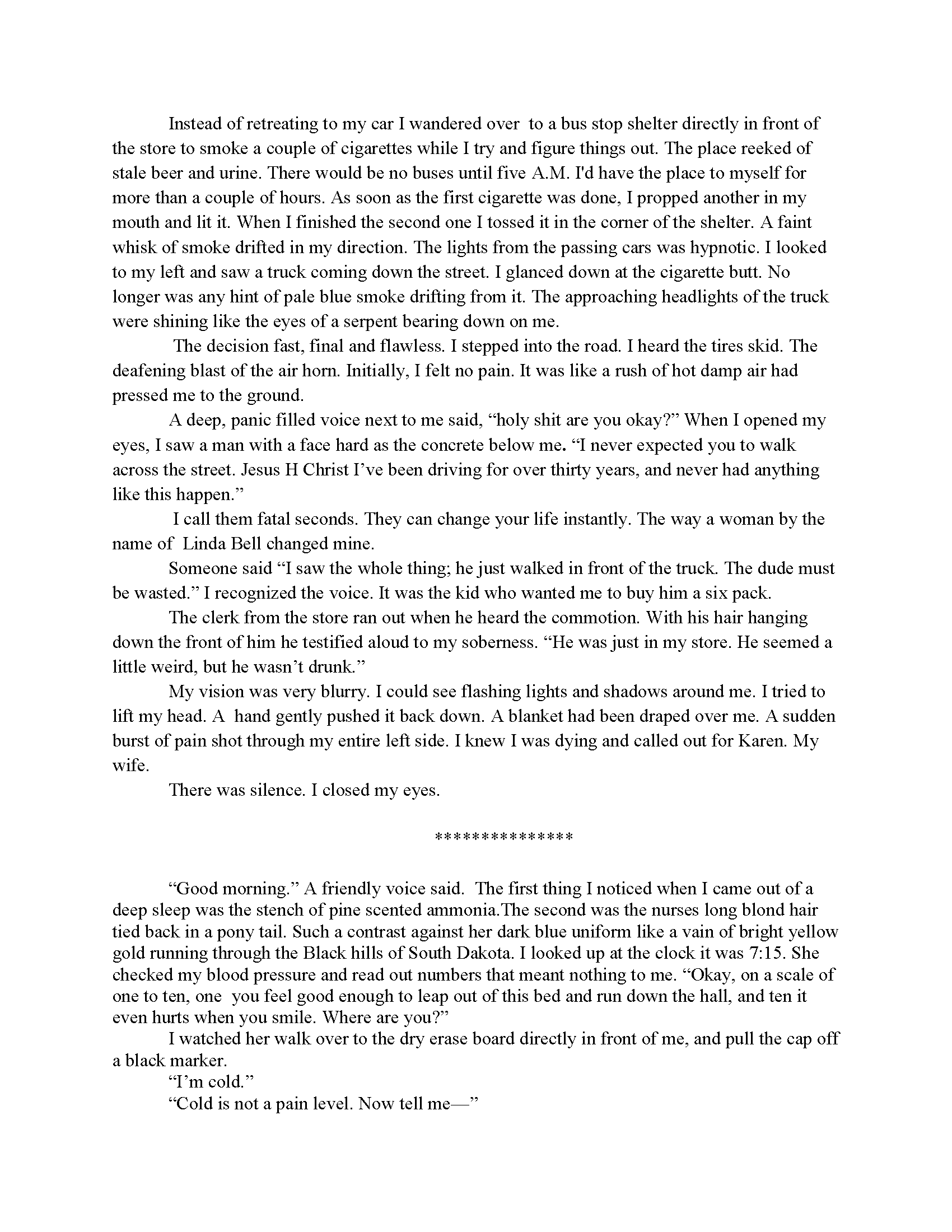

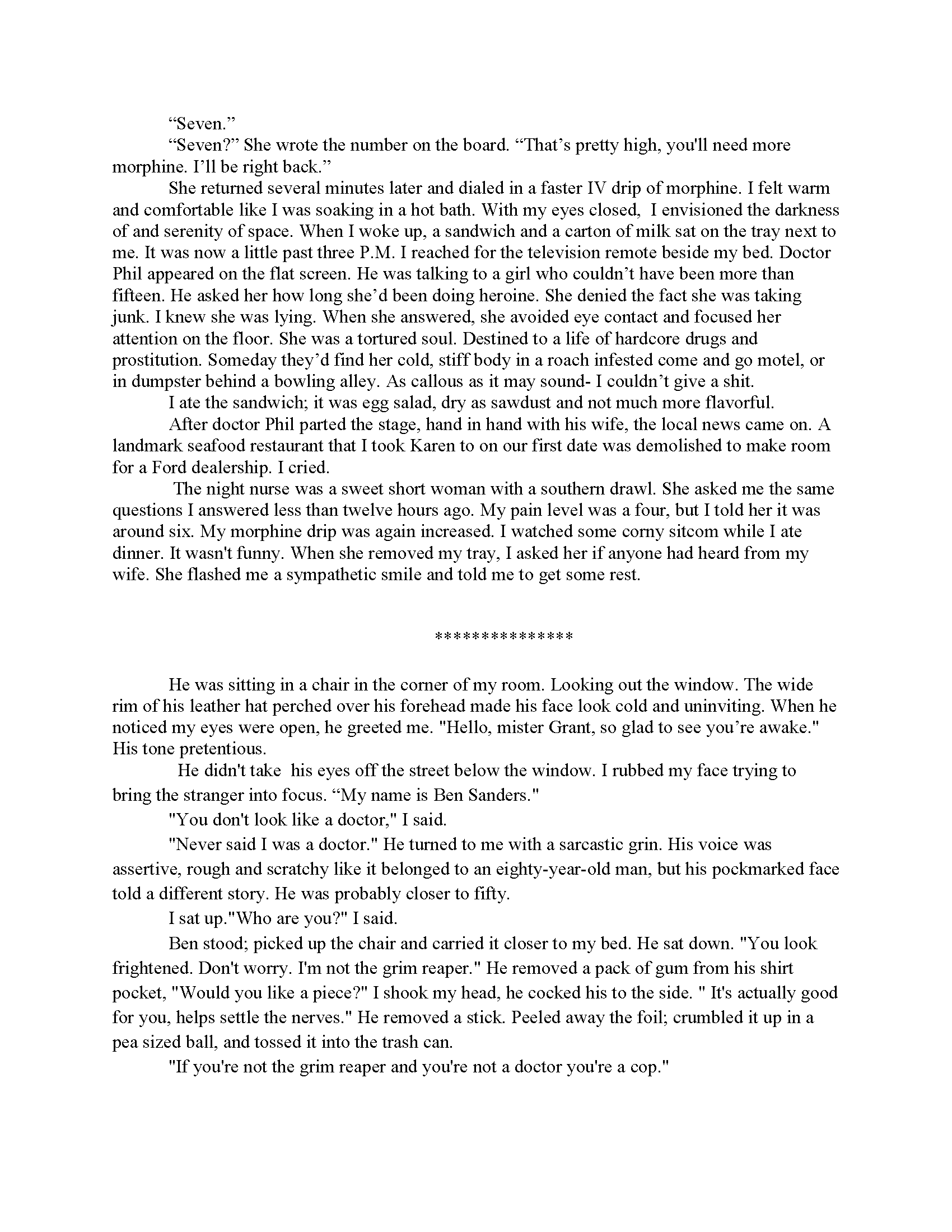

In this episode, Clark and I discuss point of view in our critique of “The Second Prayer: A Confession for the Dead,” a thriller short story by David L. Storm. Point of view seems like a straightforward choice. It's the filter through which the reader experiences your story: Each option has advantages and disadvantages and can produce vastly different results. If you have to change it in the revision stage, it's a big job, but worth it if you find the right POV for the story you want to tell.

In our editorial mission this week, we share a list of questions to ask when you choose the story's POV for your first draft and later during revision. Our author has graciously allowed us to include the entire text of his story, and you'll find that below, after the inline critique.

Listen to the Writership Podcast

Wise Words on Point of View

“Selecting the best point of view from which to tell a story can be puzzling. Because you originally conceive an idea in first or third person doesn’t mean it has to stay that way. Often it’s good to rewrite the story in another person to see how it changes. Sometimes writers, after a number of drafts, have realized that the real story lies elsewhere—in the mother’s view of the daughter, not the daughter’s view of the mother. Such changes in perspective have resulted in breakthroughs that have astonished their own authors.

”

Additional Notes

Grab an official copy of David L. Storm's The Second Prayer: A Confession for the Dead!

Clark mentioned two stories films in which the viewer sees the story from multiple points of view. They are Roshomon and Vantage Point.

Editorial Mission—How to choose your story's point of view

When deciding and reviewing point of view, consider the questions listed below. No single factor should necessarily determine your choice. As Clark mentioned, when you’re deciding on a POV, it’s a great to experiment with different options. Try different characters as well as first, third limited, and omniscient to get a feel for how the story feels most natural.

- How many perspectives do you need? (The shorter the work, the more likely you’ll want to stick with one person.)

- Do you need an objective or subjective narrator?

- Do you need to contrast character’s actions? (As Nick Mamatas noted: “If a character’s thoughts match his or her actions exactly, the thoughts aren’t interesting and are probably not necessary to share.”)

- What are the advantages and disadvantages of each choice? This Writer’s Digest post lists the advantages and disadvantages of each point of view.

- Whose story is this? Who has the most at stake? Who changes the most as a result of the events of the story?

- Who has the best vantage point? Whose perspective can best convey the story to convey your controlling idea or theme?

- Who has the best and most interesting voice?

- Do you need more distance or intimacy? (You can adjust narrative distance within the POV, but this is accomplished far more easily in third omniscient than third limited and first.)

- Which character has a secret you want to avoid revealing early in the story?

- Consider the MICE quotient and who can best reveal the events of the story given the main factor in yours. (Not mentioned in the episode, but check out the advice for our author for a brief discussion.)

Editing Advice for Our Author

Dear David,

Thanks so much for sharing your story with us! “The Second Prayer: A Confession for the Dead” has a fascinating premise for a psychological thriller with so many great elements. The twist you have set up is spectacular and ambitious for a short story. I love that you’ve taken on this challenge!

Our biggest suggestion is to reconsider the point of view, including the character and possibly the type. Point of view is important in every story, but particularly critical when you want to reveal some facts and hide other facts. It’s hard to hear because this would mean a substantial rewrite, but you have stellar ingredients for a huge twist, and we suspect that a different point of view would make this powerful.

As Clark mentioned, we couldn’t think of any elements that we would cut or add (except that we think you could expand this into a novella or a novel)—our main advice is about how and when you reveal the events of your story.

The key to this can be found in your logline: Two people know why Jimmy stepped off the curb in front of a truck, and one is dead. Since Jimmy knows, he could simply tell us, and from his point of view, there is no mystery about why he did it. (Unless the story were about him waking up in the hospital and having no recollection of the facts of his recent past. But that’s quite a different story.)

The detective, Ben Sanders, doesn’t know why Jimmy acted the way he did, but wants to know so he can build a case against Jimmy in the death of Linda Belle. He’s a great character to guide us through the story and ask the questions we would want to ask.

Another way to look at it is through the lens of Orson Scott Card’s MICE quotient story factors: milieu, idea, character, or event. I hadn’t thought about this before we recorded, so we don’t talk about it in the episode. I share a brief explanation here, but if you want to find out more, listen to episodes 6.10 and 8.20 of the Writing Excuses podcast and Karen Woodward’s excellent posts on the topic.

Within that system, you could frame this as an event or character story, but the logline and genre point to an idea story: Jimmy Grant had it all, so why did he step off a curb in front of a truck? And the reason this is important is that this single fact changes how we see everything in the story.

As written this is an idea story, so it begins with a problem to be solved (building the case) or a question to be answered (Ben must know why this happened). If the question were, how am I going to get away with this, then Jimmy might be the best POV character, but again the powerful twist comes from the question of motive, and Ben is the person in this story who wants to know that and with whom the reader is most closely aligned.

You have such a fantastic and inventive twist! Thank you for the opportunity to talk about this and for trusting us with your words.

All the best,

Leslie & Clark

Line Edits for Our Thriller Short Story

The Full Story

Image courtesy of luciezr/bigstockphoto.com.

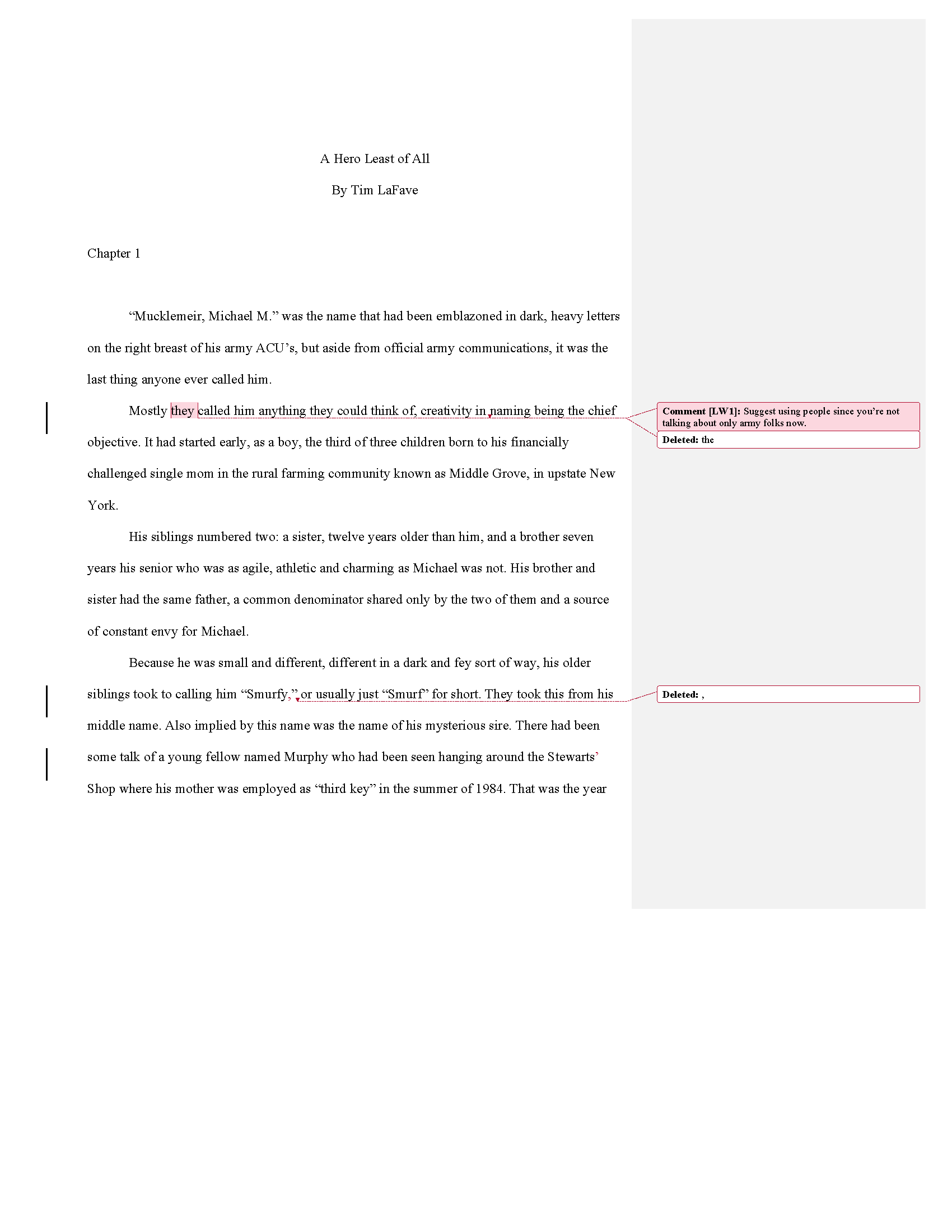

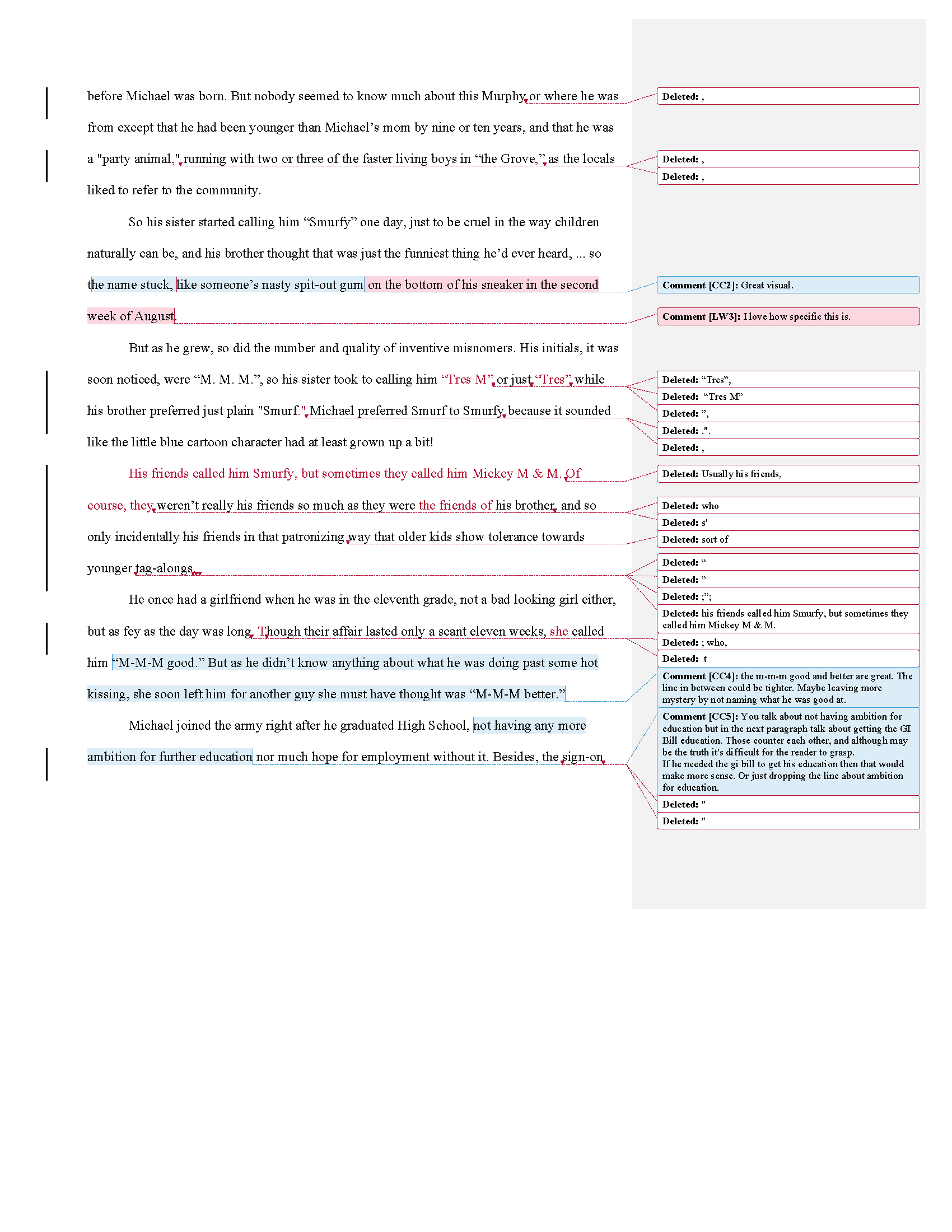

Ep. 101: Check Your Narrative Distance

In this episode, fiction editors Leslie and Clark critique the beginning of Osweyth, an epic fantasy novel inspired by Cornish folklore by JM Hudson. They discuss narrative distance, omniscient point of view, and moving smoothly between vantage points. They also talk about the weather as a character in the story, lush prose, sentence and paragraph length, and commas. The editorial mission asks you to check your narrative distance, that is how close your reader is to the character or narrator.

Listen to the writership podcast

Wise words on narrative distance

“Psychic Distance is a concept which John Gardner explores in his book The Art of Fiction, and I think it’s absolutely crucial, not difficult to understand, and not nearly talked about enough. You’ll also find it called Narrative Distance because, basically, it’s about where the narrative (and therefore the reader) stands, relative to a character. Another way of thinking of it is how far the reader is taken, by the narrator, inside the character’s head.”

Additional Resources

The useful article about narrative distance we mentioned can be found on Emma Darwin’s site, This Itch of Writing.

The comic book writer Clark mentioned is Joshua Crowther.

Don't forget to check out Clark’s new course, Advanced Novel Writing with Harry Potter!

Editorial mission—check your narrative distance

Narrative distance (also known as psychic distance) is a term to describe how far away the reader is from the character or narrator who’s revealing the story. Even within a single point of view, you can be far away from the character and her experience (the equivalent of watching a scene from the back row of a theater) or actually within the character’s experience and feeling what they feel or knowing their thoughts in their own words.

This element is also related to showing and telling because the greater the distance between the reader and the character, the more the narrator or character tell us about what’s happening rather than showing us or allowing us to experience it. The distance you need to tell your story effectively will vary across the entire book and within individual scenes.

The examples from John Gardner and Emma Darwin in her post we mentioned in the episode will help you get a better feel for the extremes and the levels in between.

Once you have a sense of these levels, check a scene of your own. Consider the narrative distance as written then what you think would be ideal for what you need to accomplish and what you want to show the reader. Use the following elements to assess then adjust the narrative distance within the scene.

- Word choice and sentence structure. Is the prose in the character’s own voice and using words she would use, or in the voice of an objective, story-telling narrator?

- Which details about the setting and characters are revealed? Things only the character would know and notice? Is the reader told about feelings or opinions regarding the details, or are these conveyed through the character’s actions or words?

- Are there details the POV character wouldn't normally think about?

- Do you hear the character’s direct thoughts or about what she’s thinking?

- Including thought verbs (e.g., think, know, believe, understand, realize, want, hate, remember) or tags for observations increases the narrative distance.

- Explanations about the location and what’s happening do the same.

- The character’s own facial expressions unless she’s gazing in a mirror or reflective surface increase the distance as well.

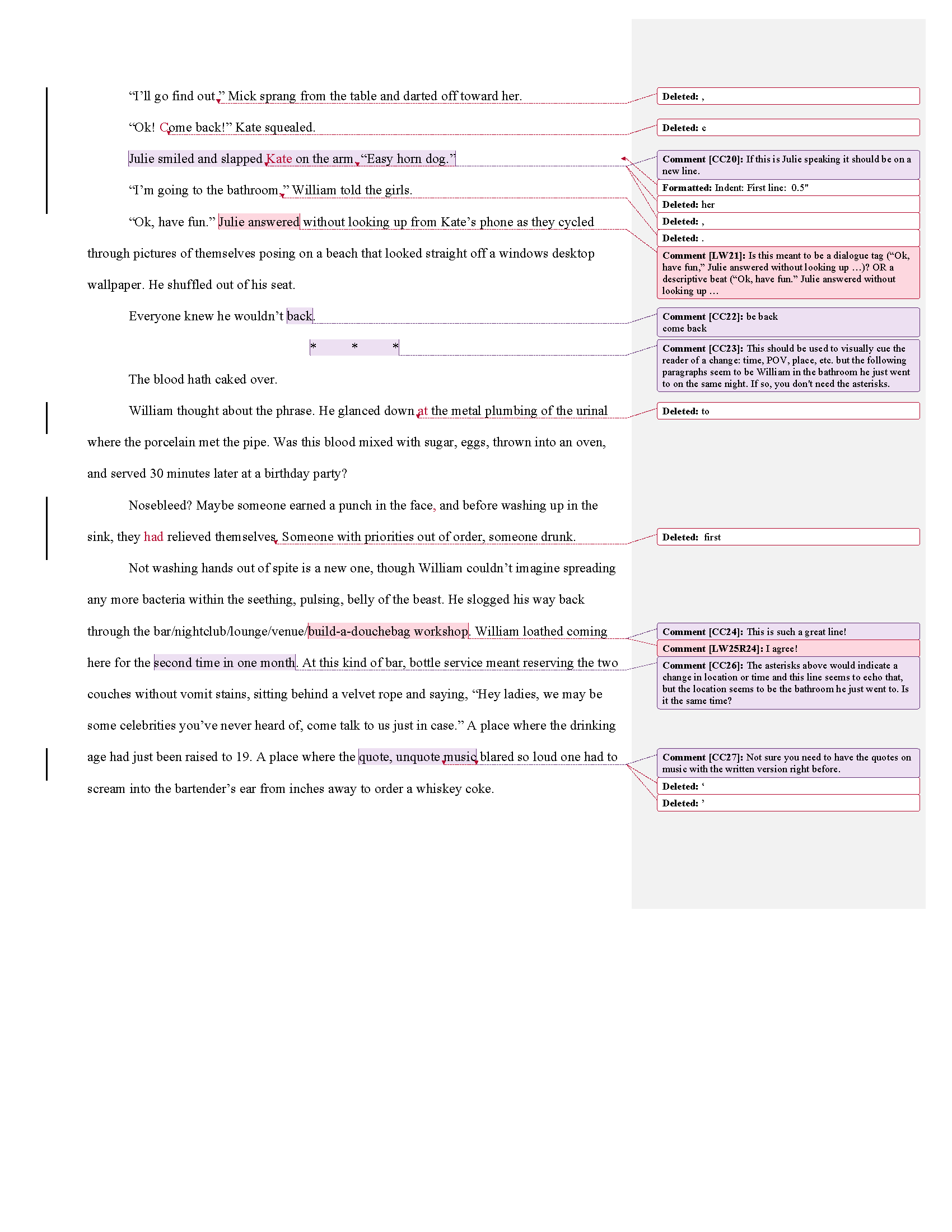

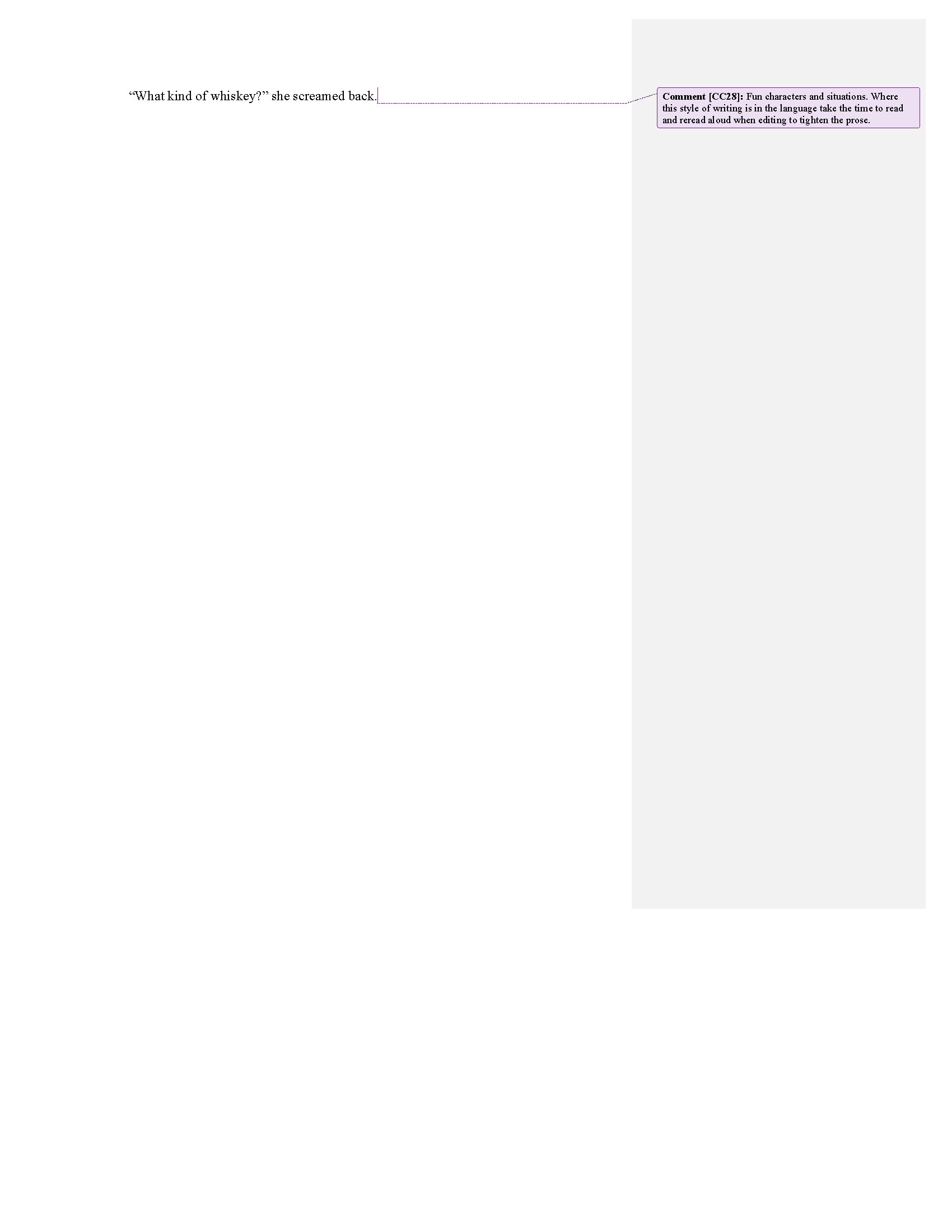

Editing advice to our author

Dear J M,

Thank you so much for your submission! You’ve provided us with the perfect opportunity to talk about narrative distance (aka psychic distance) and how it affects point of view in stories.

You’ve used third person omniscient POV so the reader can observe the action from many vantage points, which is helpful in an epic story like this. The way you employ narrative distance helps us ease into the location and becoming familiar with the characters.

We have a lovely progression from a tiny figure, to a small girl, to feeling what she feels and realizing she is only four years old. Then we hear her speak and see her interact with Jowan. (By the way, she is a captivating character, and I feel a strong urge to read on to find out who will win the battle of wills between her and her father.)

There is a similar progression with Jowan from soldiers noticing that something is amiss to eventually learning that he has a pet name and no small affection for the feisty four-year-old, who also happens to be of royal blood.

The movement from Byhan to Jowan is smooth, not jarring. You’re training the reader how to read your book. And, I suspect we are seeing very characteristic moments for both these characters: Byhan lying in the mud during a squall and feeling the vibration of the waves crashing against the stone beneath and Jowan fearing for her safety, scolding her (though not harshly), and remembering that the odd things about her in a commoner’s child would probably mean death.

There’s not a lot going on in this scene in terms of action: A young noble girl rushes outside in a violent rain storm and falls in the mud. Soldiers notice her, and one in particular rushes to see that she’s all right. While he scolds, her father arrives and then another person (possibly her mother). But in execution you’ve added so much. This is a great opening scene that reveals way more than simply what happens.

As Clark mentioned in the episode, you’ve avoided presenting a laundry list to describe the characters, and instead, helped us get to know them by showing us who they are in their environment with their actions.

The way you’ve employed the weather as a character in this opening supports the story well. Your lush and poetic prose and word choice are a great fit for an epic fantasy inspired by Cornish folktales.

Our suggestions for you relate to items you’ll want to consider in the later stages of revision. You have a lot of long, complex, and compound sentences, and there’s a lot of information to hold in the mind before the reader reaches the end. In part, the description is forceful (not forced), like the storm. This is great, but we were wondering about sustaining this throughout the 100,000 or more words of the story. (You may have already considered this.) When you start editing at the level of paragraphs and sentences, consider the reader’s experience and make sure the level of detail and the complexity of the sentences are manageable. It’s not that there are no short sentences, it’s that the long and complex ones stand out.

Beta readers, especially those who are close to your ideal reader, should give you some great feedback on this point. Some readers enjoy a challenging read, so it’s more about a good fit than a particular word count per sentence. (Does that make sense? I have a book I’m reading for fun that has long, complex paragraphs with very little white space on the page. I love it, but not everyone will want to read The Sea & Civilization: A Maritime History of the World.)

Watch for comma usage (again, this is something you shouldn’t wrestle with until later stages of editing). I’ve marked some instances in the submission below. With complex prose, you’ll want to make sure the punctuation aids clear understanding rather than following the rules. Still, readers are used to seeing punctuation show up in a certain way, so I recommend keeping as close to "normal" as possible. Clear as mud?

The last thing I want to mention is that you handled the Cornish words well in this opening (even though my pronunciation was terrible!). The meaning, or enough of the meaning, was clear from the context in each case.

Thanks again for your submission!

All the best,

Leslie and Clark

Line edits for our epic fantasy story

Ep. 100: Answers to Your Burning Questions about Writing and Editing Fiction

In this episode, fiction editors Leslie and Clark celebrate 100 episodes. They depart from the regular format to answer your questions about writing and editing. They discuss passive voice, pantsing vs. plotting, head hopping, how long your story should be, and how to write character thoughts. This week’s editorial mission is about finding your strengths and weaknesses.

Listen to the Writership Podcast

Wise Words on Writing

“The “rules” can be broken, of course, if the violation isn’t noticeable, or if enough is achieved by doing so; but to break the rules of point of view unwittingly, with nothing accomplished by it, is to harm the story foolishly¬ for the reader is sophisticated, he will see the error and discount the work, and even if he is so innocent of fiction techniques as not to notice it consciously, he will have an uneasy feeling, vague as it might be, that something has gone a bit wrong.

”

“Writing talent is probably more common than anybody suspects, and it is less important to a writer’s career than most people believe. I have known highly talented young people who for one reason or another have dropped out of writing and never reappeared, and I’ve known people with very modest talents who by sheer determined effort have become professionals. I can’t pump determination into you, and wouldn’t if I could. What I can do is try to tell you what you’re in for, and help you acquire the skills that make the difference between the amateur writer and the professional.”

Advanced Novel Writing with Harry Potter

Find out more about Clark's new course: Advanced Novel Writing with Harry Potter.

Get your 100 Quick Writing Tips

To celebrate the Writership Podcast's 100th episode, we're giving away a free download with 100 quick writing tips! Click here to get it now.

Introducing Patreon

As you may know, hosting and technical support for the show is provided by our brilliant corporate sponsor, Author Marketing Club. But we're now inviting listeners to sponsor our time in producing the show, so we can continue to demonstrate editing in action and expand the resources we offer to help you write stories that are shipshape and Bristol fashion.

If you want to support the Writership Podcast, you can donate a small dollar amount each month through Patreon, a trusted site that connects creators with their fans. As a token of our thanks, we'll give you some goodies every month and memorialize your name on the site!

Editorial Mission—Find Your Strengths and Weaknesses

Look at your body of work, published or not, and think about your writing habits. What do you notice? What are your strengths? How can you leverage them to improve your process or results? What are your weaknesses? Find a resource to deepen your knowledge in one area you’ve identified as a weakness. (Need one? Write to us at hello@writership.com for a suggestion.) Through determined effort, apply what you've learned until you gain mastery. Reassess regularly as you practice and receive feedback. Choose new weaknesses to study and master.

Image courtesy of MartinM303/bigstockphoto.com.

Ep. 99: Have You Revealed Your Character's Essence?

In this episode, Leslie and Clark critique the first chapter of Let’s Go Inwards, a science fiction novel by Jake. They discuss revealing character. Unlike screenwriters, we can’t rely on actors to show the audience who our characters are. But we have access to and can expose our characters’ thoughts and motivations in other ways. This episode also includes suggestions for word choice and figurative language.

Listen to the Writership Podcast

There is some adult language in this episode.

Wise Words on Creating memorable Characters

“The creation of character presents special problems for writers of fiction. The playwright or screenwriter can hope for arresting actors whose appearance, presence, mannerisms, and delivery will create memorable characters. As a writer you have only your words on the page. You cannot even rely on illustration, as nineteenth-century writers often did. At the same time, there’s nothing more important to your fiction than your characters.”

Send Us Your Questions!

Click here to submit your questions on writing and editing, for Leslie and Clark to answer in the 100th episode.

Editorial Mission—Revealing Character

When you revise your scenes look for the ways you have revealed character. Look at their actions, what they say, what they think, how they react to people and the setting, how people react to them. Be sure that you’ve revealed your characters’ essence rather than presented what they look like, which though important, is only one way to reveal character.

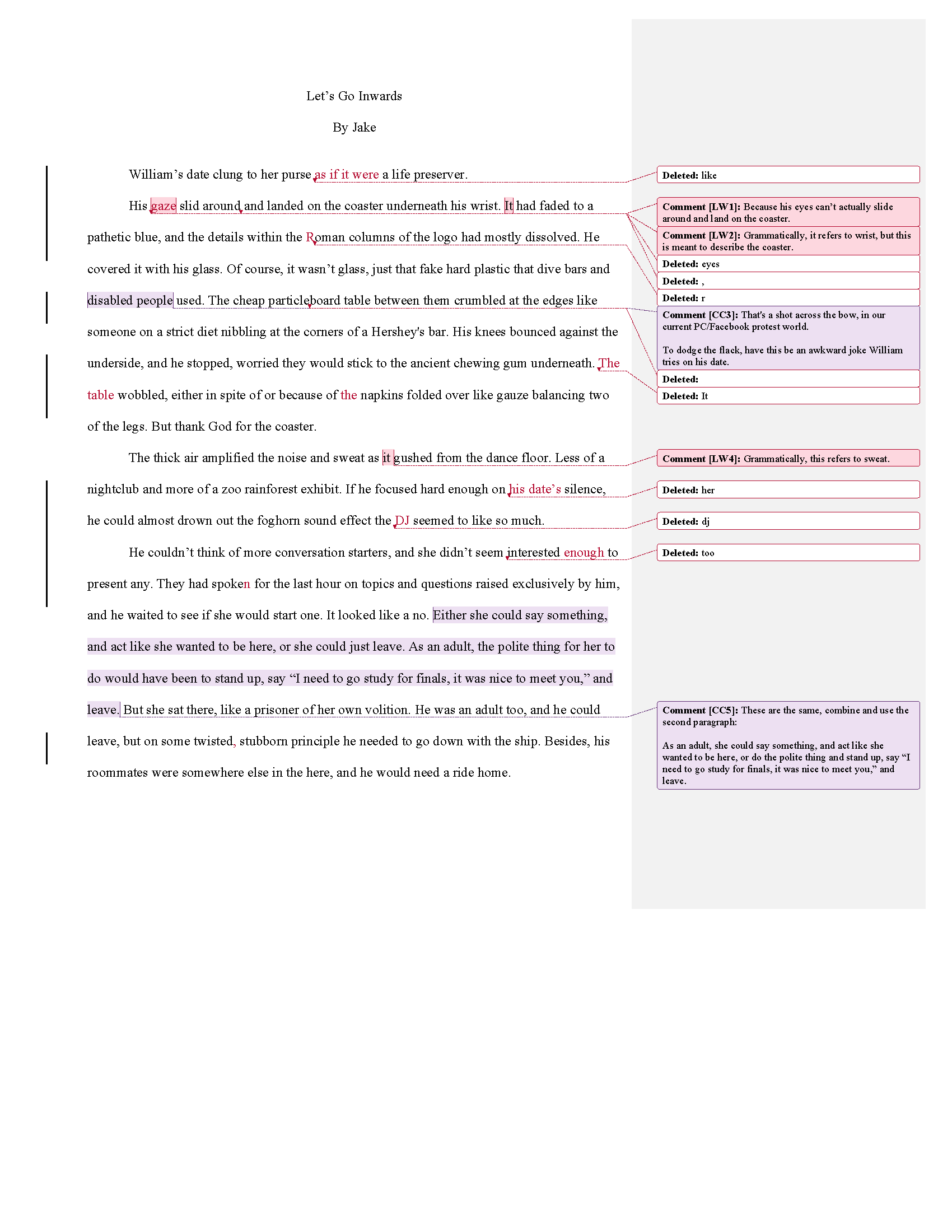

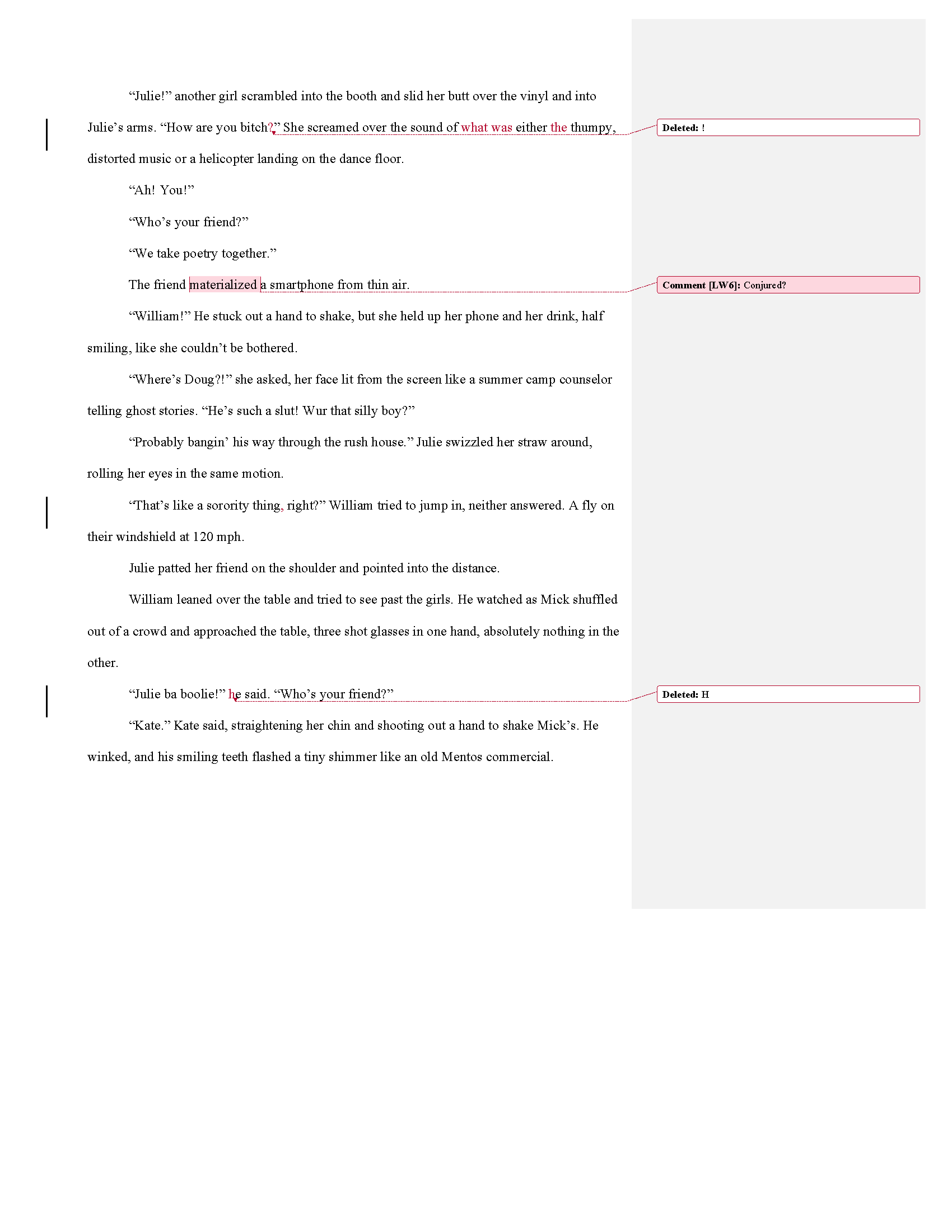

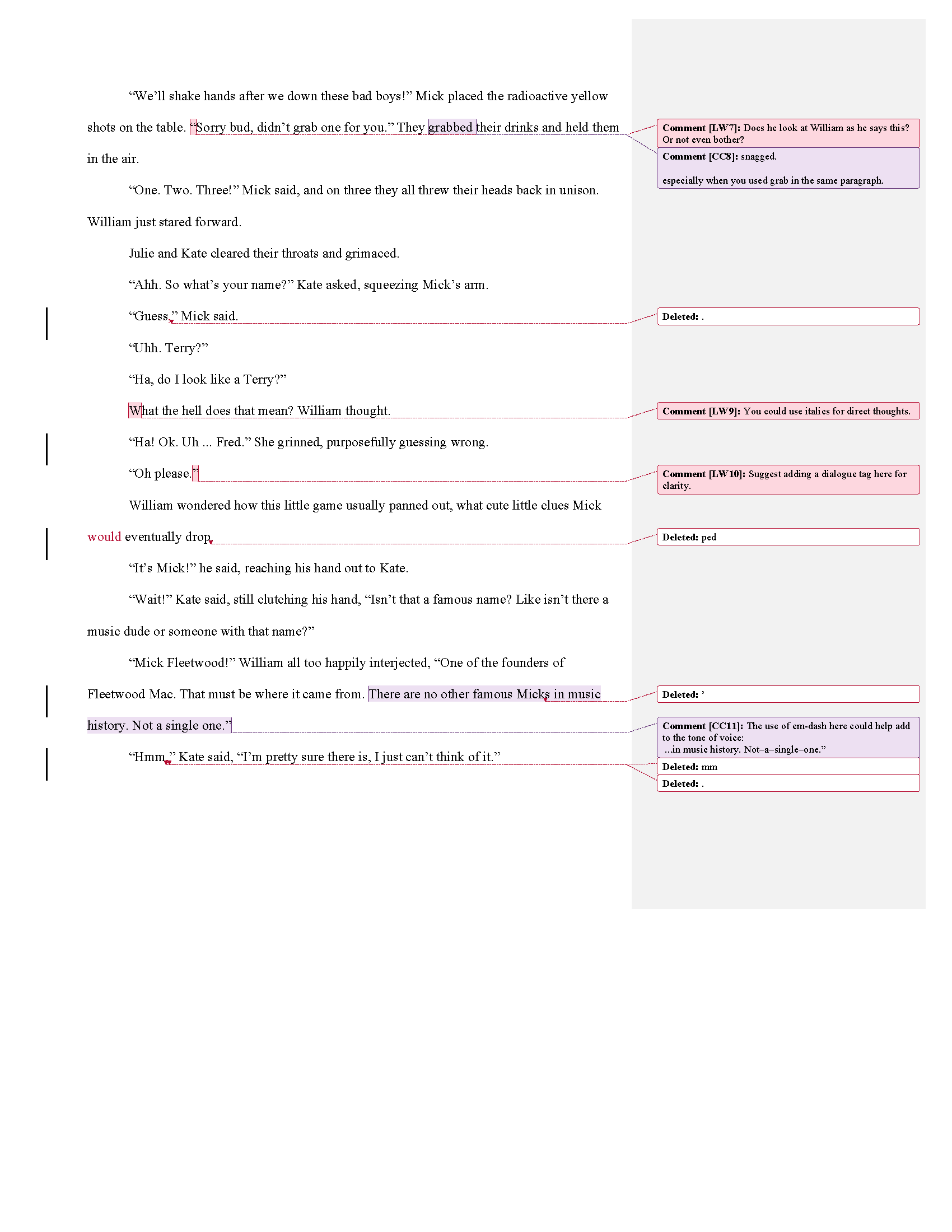

Editing Advice to Our Author

Dear Jake,

Thank you for your submission!

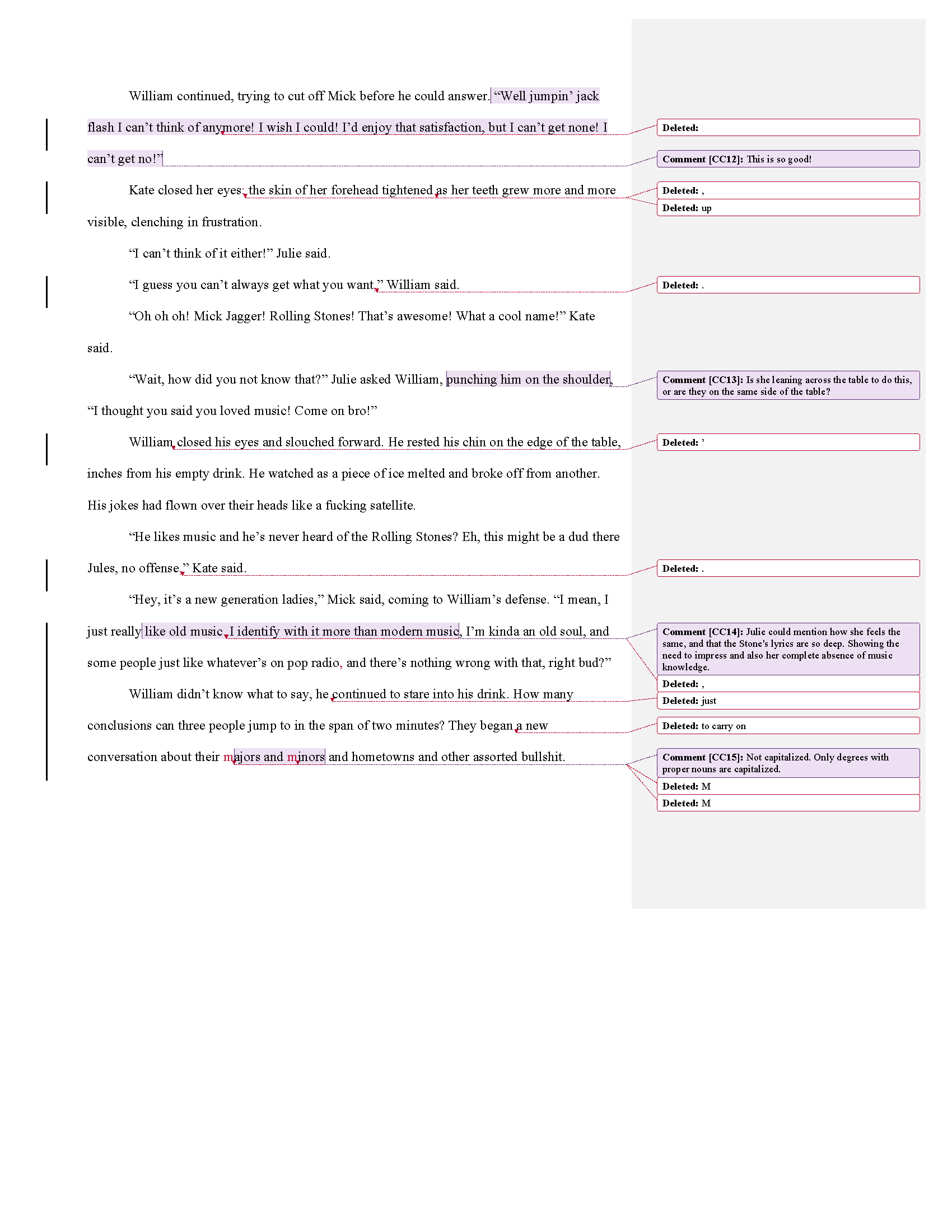

One of the main jobs of a story’s opening is to help the reader get to know the main characters. You’ve done a nice job of revealing who William is through a variety of means, including his thoughts, other people’s reactions to him, the things he notices, and his action (or lack of it since he doesn’t act on the urge to follow the bartender right away). He’s clever, opinionated, and out of his element. We get a clear picture of Julie, Kate, and Mick through William’s eyes as well in what he notices about what they do and say.

The transition to the bathroom at the end of the submission tripped us up a little. Since there isn’t a big break in time or place, we’re not sure you need the asterisks.

We suggest being mindful of metaphors and similes. Everything you included in this excerpt is great, but there are so many of them that they lose their power. As hard as it is to choose, consider which one is your favorite for this opening and save the others for another time.

Some picky stuff:

Watch for pronoun antecedents so that grammatically you are referring to what you mean to. For example, in the second sentence that follows, it refers to his wrist, the closest singular noun to the pronoun.

We found some misplaced modifiers, descriptive phrases that are far away from what they modify, so that they seem to illuminate something else.

Compound predicates (e.g., I swept and mopped the deck) don’t take a comma before the and, but compound sentences (e.g., I’ll sweep the deck, and you can mop it) generally do take a comma before and.

As you revise, be mindful of dialogue punctuation. Here’s Writership’s guide to help you with this.

Thank you for trusting us with your words!

All the best,

Leslie & Clark

Line Edits for Our Science fiction Story

Image courtesy of PHOTOCREO Michal Bednarek/bigstockphoto.com.

Ep. 98: Storytelling vs. Telling a Story

Description

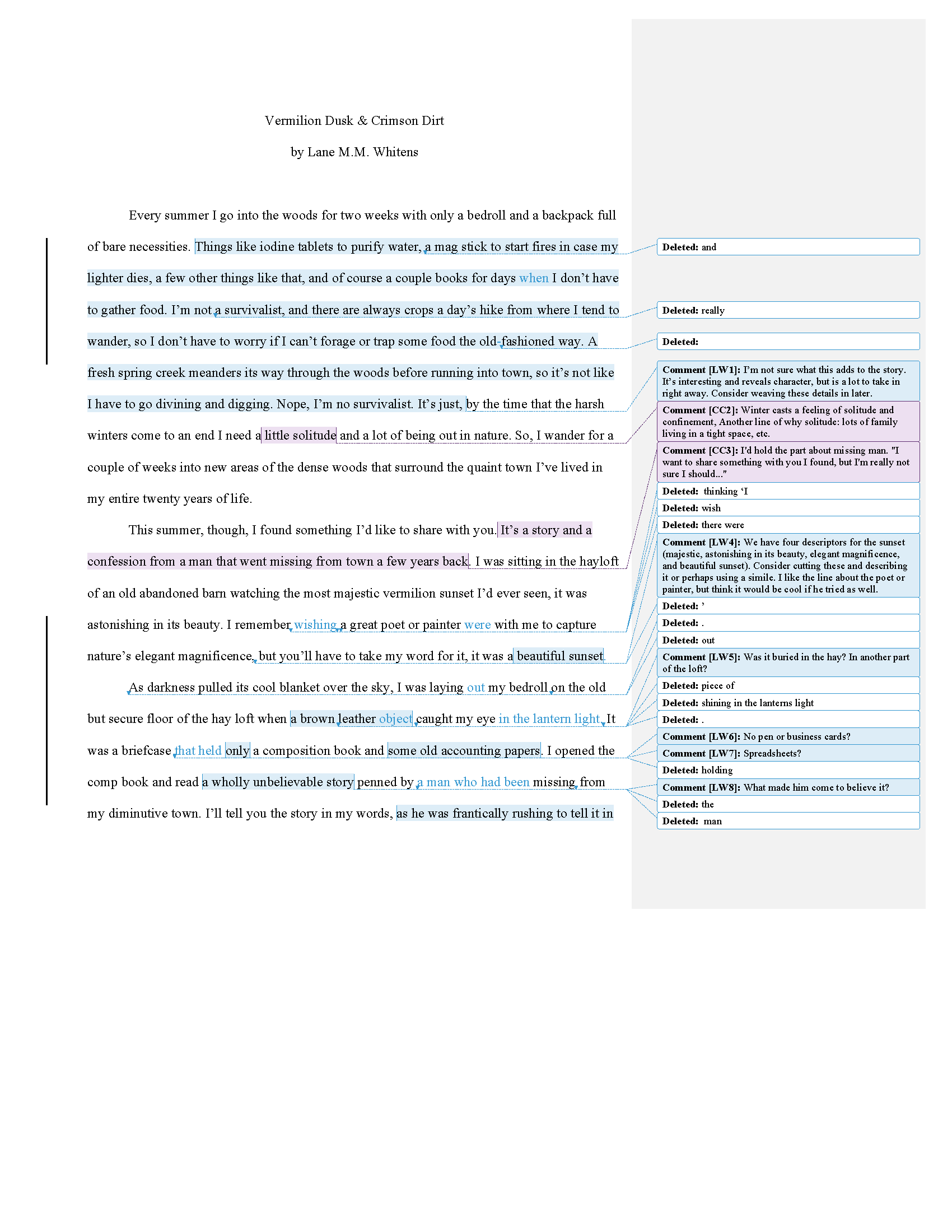

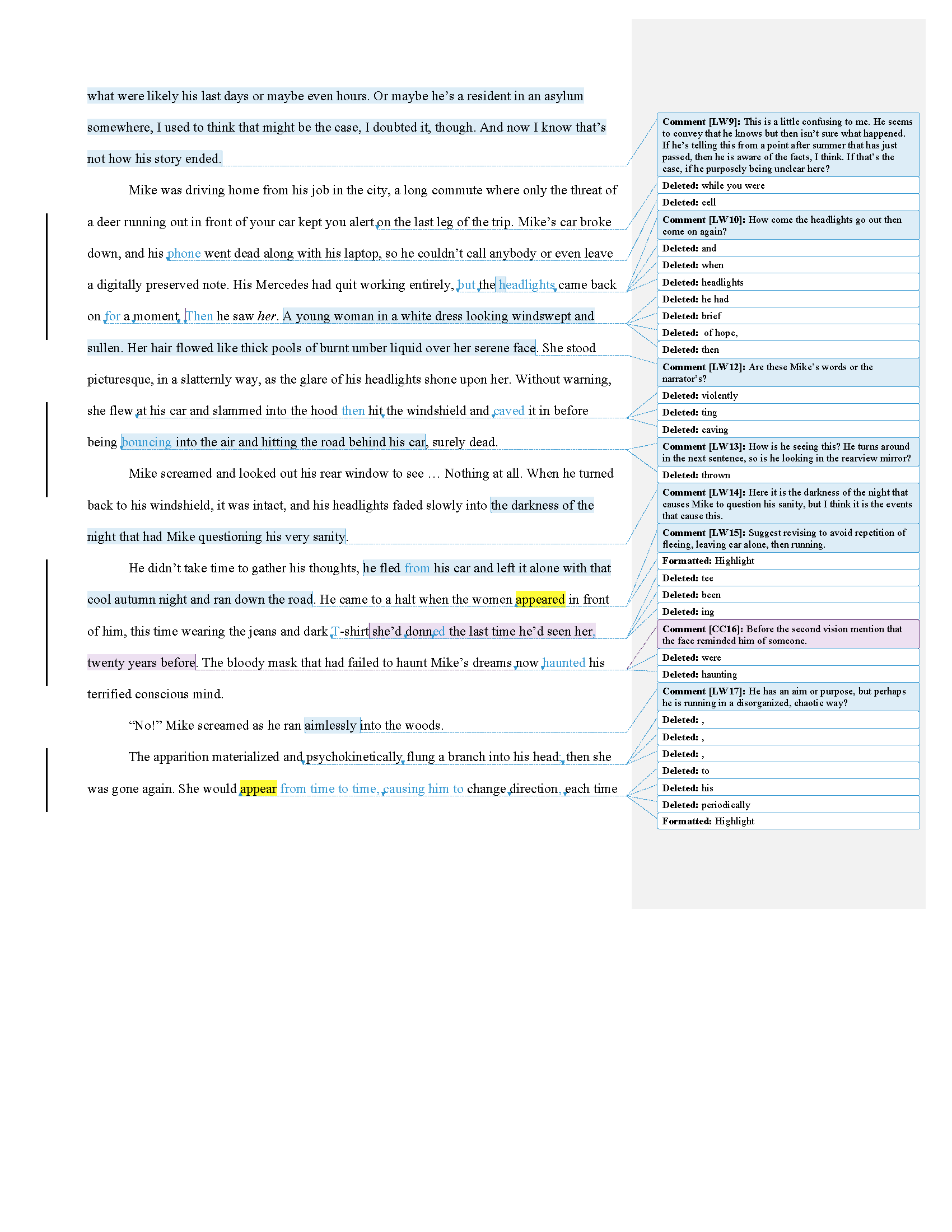

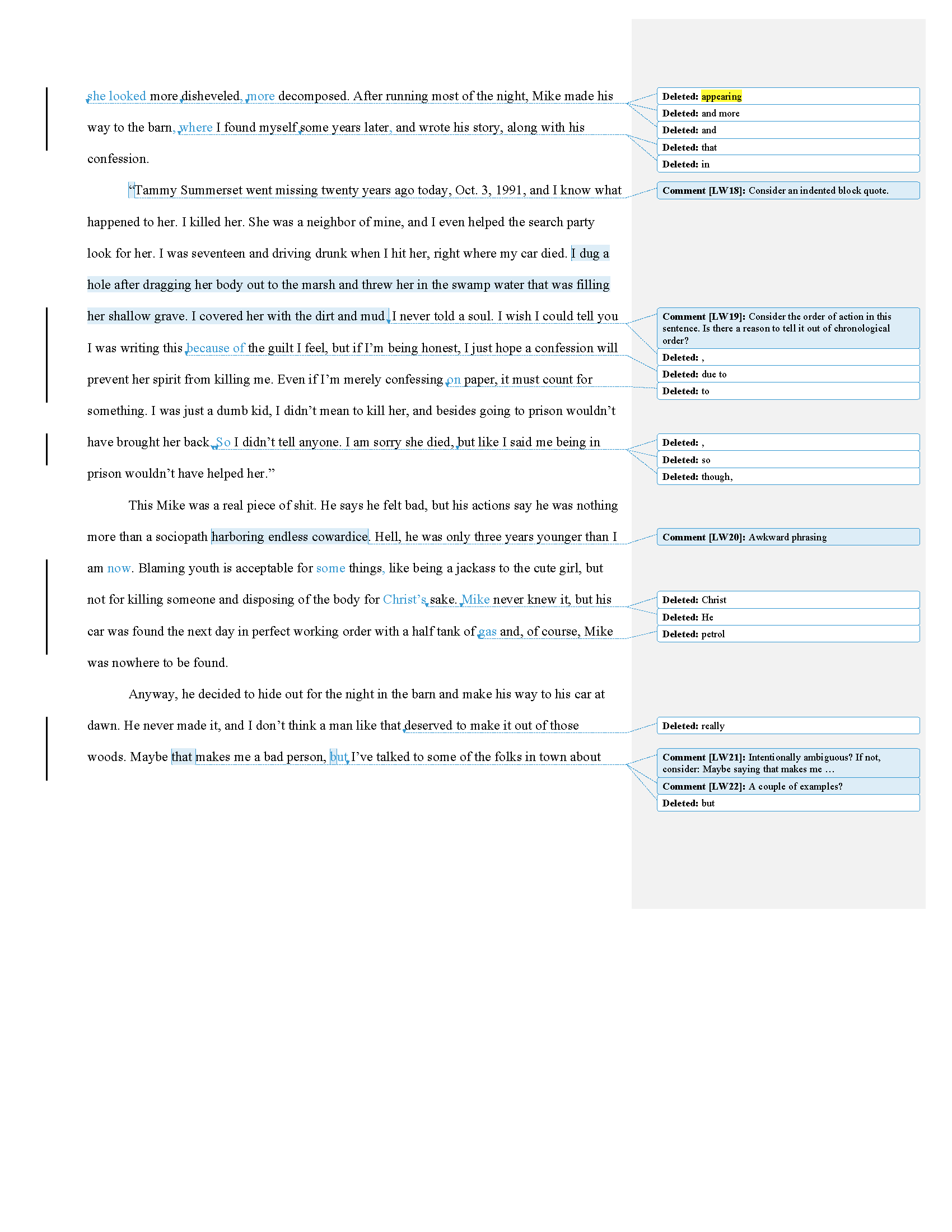

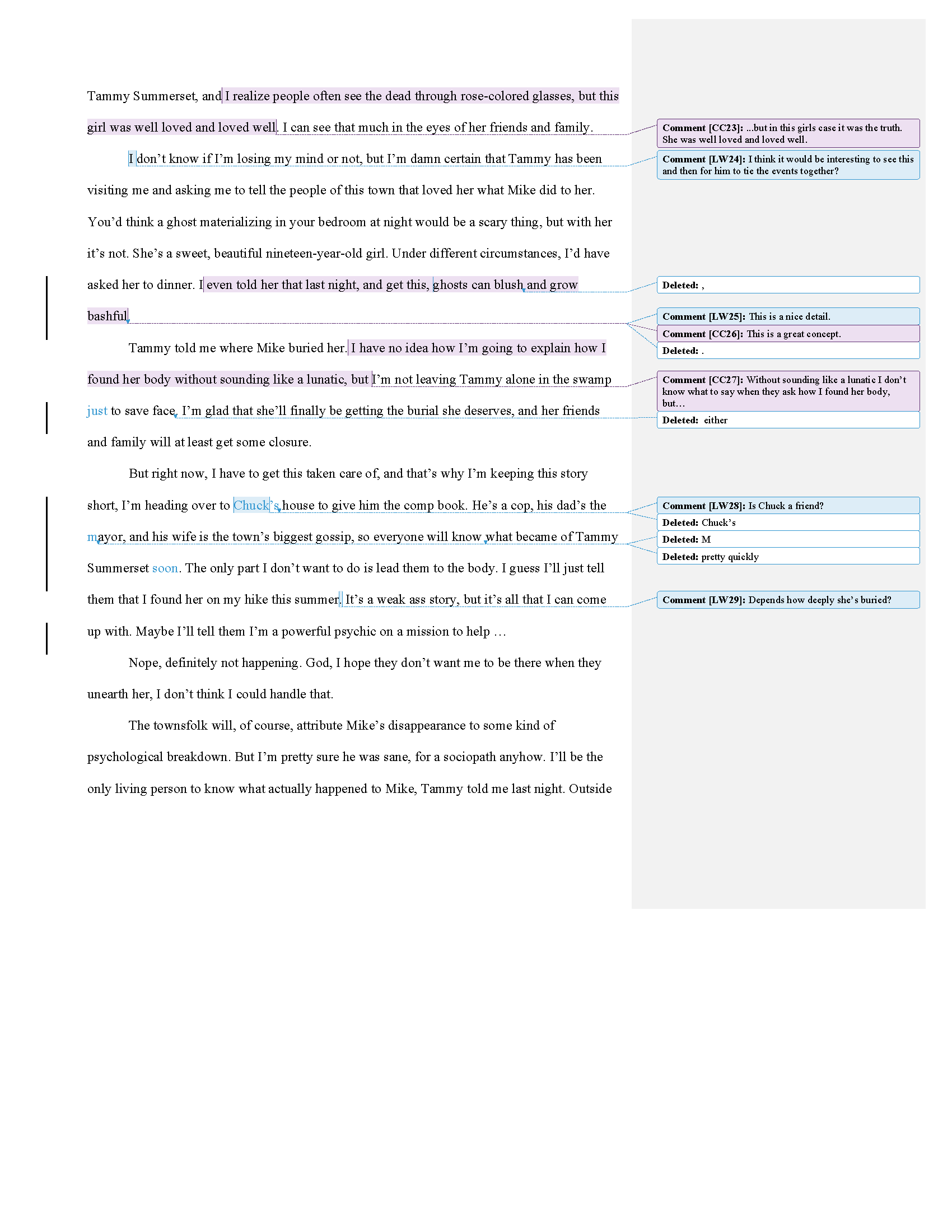

In this episode, Leslie and Clark critique “Vermillion Dusk & Crimson Dirt,”an as yet unpublished horror short story by Lane M.M. Whitens. They talk about storytelling vs. telling a story and framing stories. They also discuss -LY adverbs, and facts relevant to the story.

Leslie and Clark are taking questions for the 100th episode of the podcast. If you have a burning question about editing or storytelling, submit it here.

Listen Now

Show Notes

“Our appetite for story is a reflection of the profound human need to grasp the patterns of living, not merely as an intellectual exercise, but within a very personal emotional experience. ”

Editorial Mission—Assess Storytelling vs. Telling a Story

The key is that you can’t have emotions through telling the story, only through storytelling. Review the critical moments within your scenes. Check to see that you are "in scene," that is allowing the reader to experience what’s happening and feel the emotions you want to share. Transitions can be told, that is conveyed through exposition.

Do you want editorial missions sent directly to your inbox?

Sign up to join us aboard the Writership Podcast! We'll send new episodes and editorial missions directly to your inbox so you'll never miss out. You'll also get the lowdown on our top 12 writing, editing, and self-publishing podcasts—perfect if you, like us, want to live a fulfilling life as a writer.

Editing Advice to Our Author

Dear Lane,

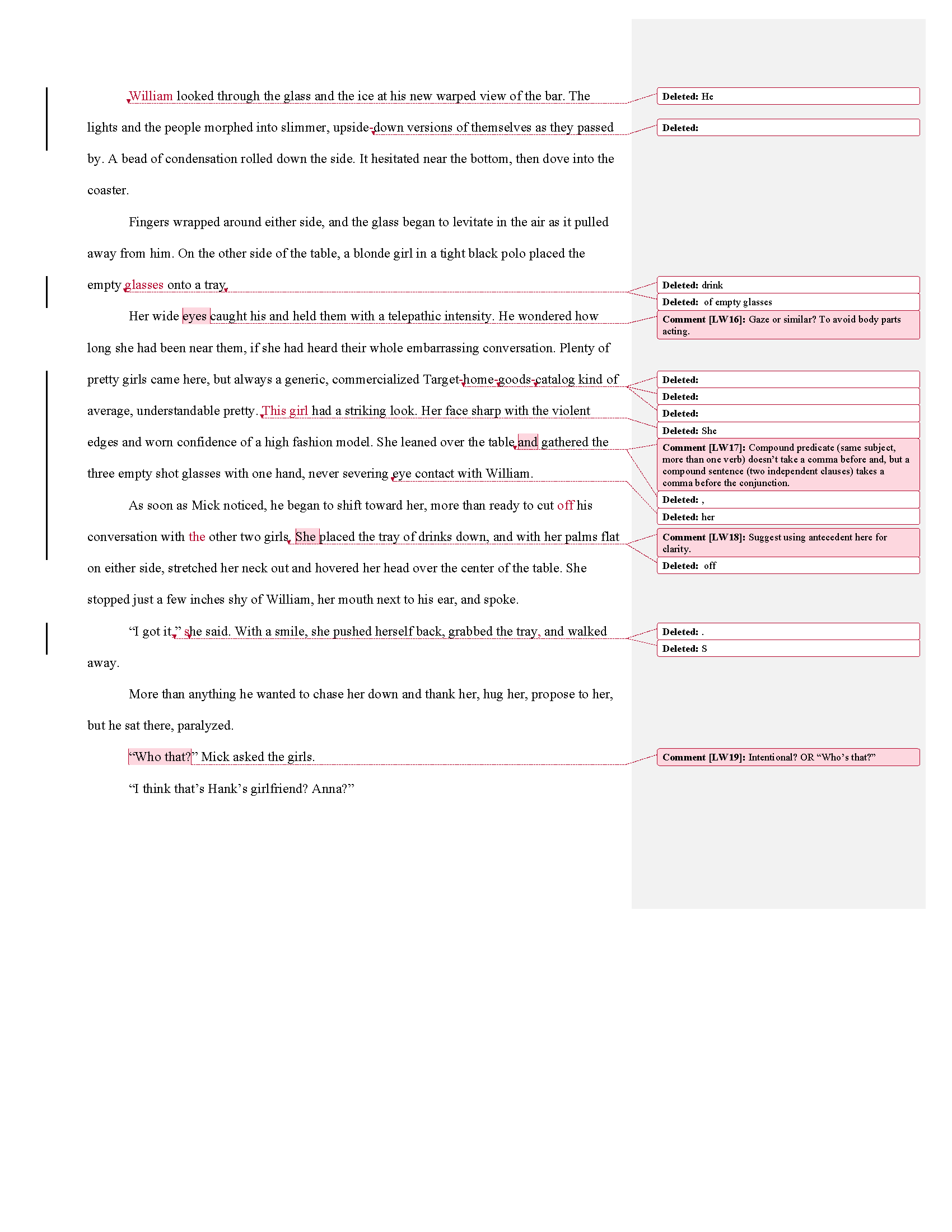

Thank you so much for your submission! You’ve chosen so many great elements for your horror short story. The narrator who delivers the tale, the other characters, the small-town and isolated woods, and the events of the story are a great setup for this spooky tale.

Our main recommendations sound like a lot, but mainly it’s revising the framing story and spending more time in scene than summary. These elements are interwoven, so we tackle them together.

In the episode, Clark talks about storytelling versus telling the story. What he’s getting at is that we are hearing about the story through the narrator rather than experiencing it through action, dialogue, and description. The problem with this is that some of the most exciting parts of the story happen offstage. For example, I would love to see the scene when Tammy’s ghost visits the narrator in his bedroom. And how does he explain about knowing where her body is?

Your framing story has the narrator telling us about how he discovered what happened to Tammy. But it’s not clear what the context is for this, and sometimes it’s not clear from what vantage point in time he’s telling us, which makes it a little confusing. It’s a good thing to keep the reader guessing, but they need one element to hold on to through the story that makes sense, a sort of anchor. So, we suggest giving it a little more structure. One idea was to open with a scene in which the narrator is telling Chuck about what he knows. You could tell this from the current narrator’s POV or try it from Chuck’s POV (consider experimenting with both?). (You can keep it open-ended. You don’t need to show whether Chuck believes him, but you could.)

If you decided to try this structure, you could open with a scene and use telling or summary to transition between scenes in the present and in the tale. You could experiment with when and how to reveal facts to the reader so that the “other shoe” doesn’t drop until you’re nearing the end of the story.

We also think you could go longer with this story depending on how you want to develop it. It’s a big story that you could expand if you feel pulled in that direction. We’ve made suggestions for you to consider here and in the episode, but these are only examples of possibilities.

Consider the use of –LY adverbs to determine are they necessary to convey meaning or contribute something to the character’s voice. Err on the side of cutting them to find verbs that would be stronger.

Thanks again for your submission and for trusting us with your words!

All the best,

Leslie & Clark

![Ep._101-Narrative_Distance_Page_1[1].png](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5274188fe4b02f841cc15eb2/1494512392133-IIGW7R5FZPBFXZON9AU6/Ep._101-Narrative_Distance_Page_1%5B1%5D.png)

![Ep._101-Narrative_Distance_Page_2[1].png](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5274188fe4b02f841cc15eb2/1494512401733-QP5XKCXVHLB6Y4XJ8VTS/Ep._101-Narrative_Distance_Page_2%5B1%5D.png)

![Ep._101-Narrative_Distance_Page_3[1].png](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5274188fe4b02f841cc15eb2/1494512406198-O60TQPJWLLCGEVWQB4SI/Ep._101-Narrative_Distance_Page_3%5B1%5D.png)

![Ep._101-Narrative_Distance_Page_4[1].png](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5274188fe4b02f841cc15eb2/1494512410229-D2TCFJQDXA91DVTJE39W/Ep._101-Narrative_Distance_Page_4%5B1%5D.png)