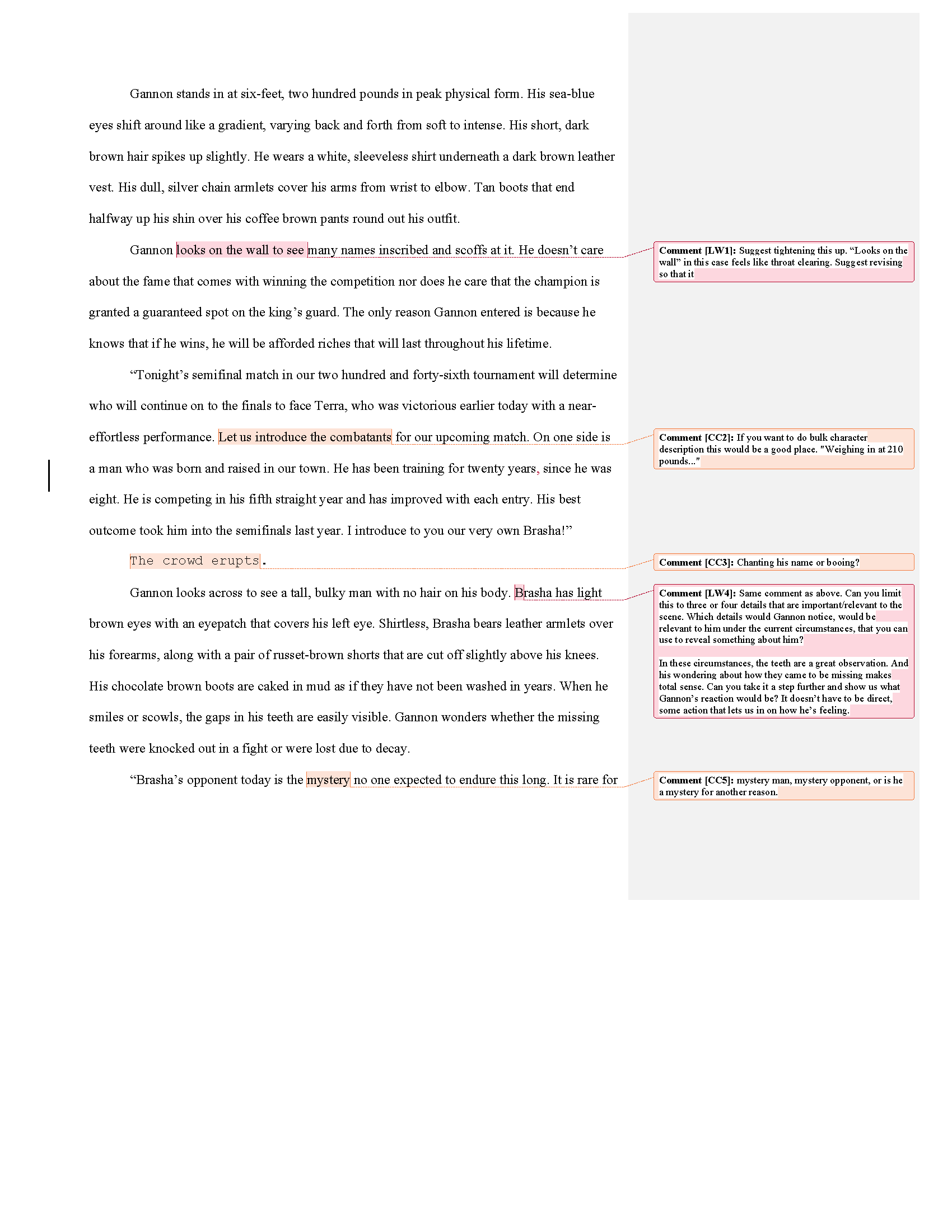

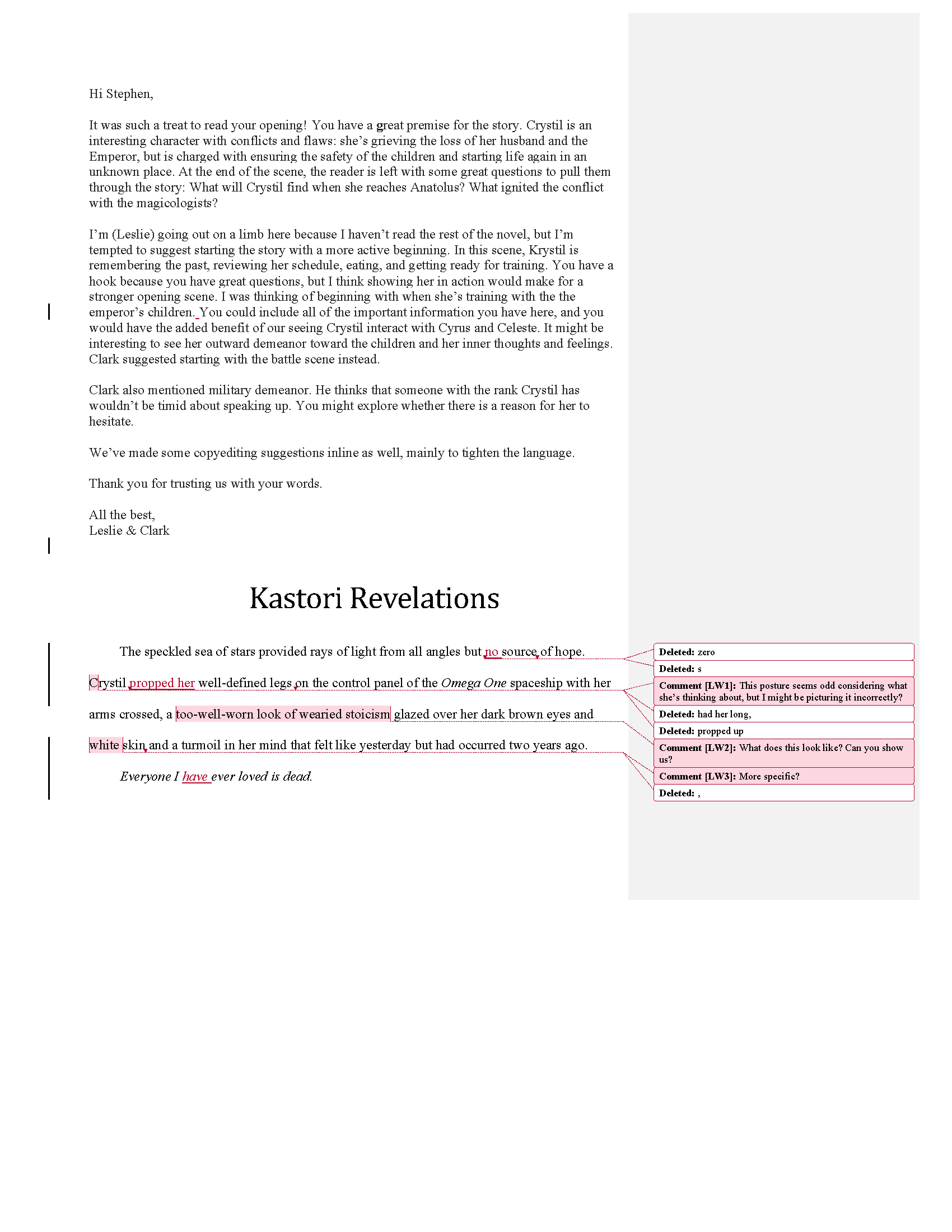

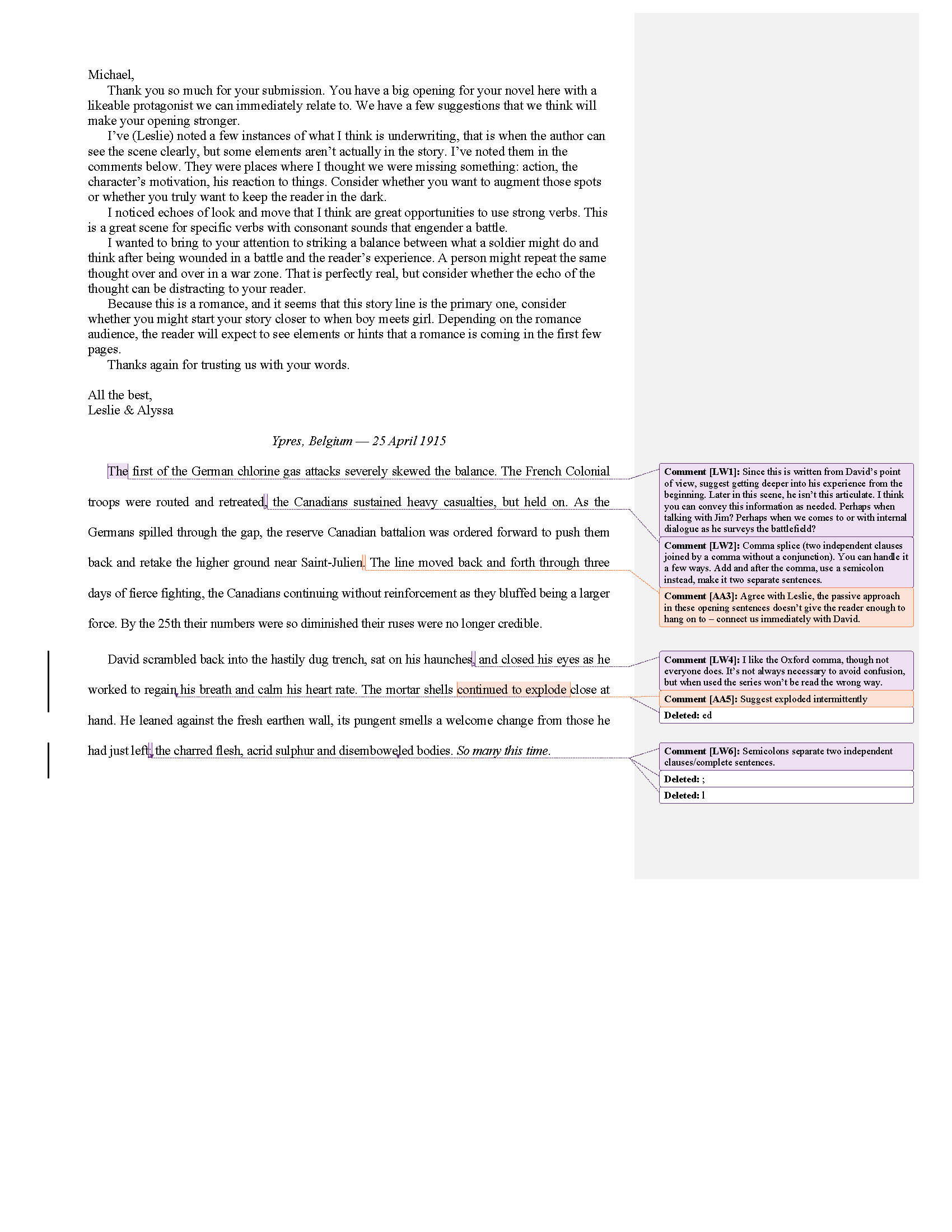

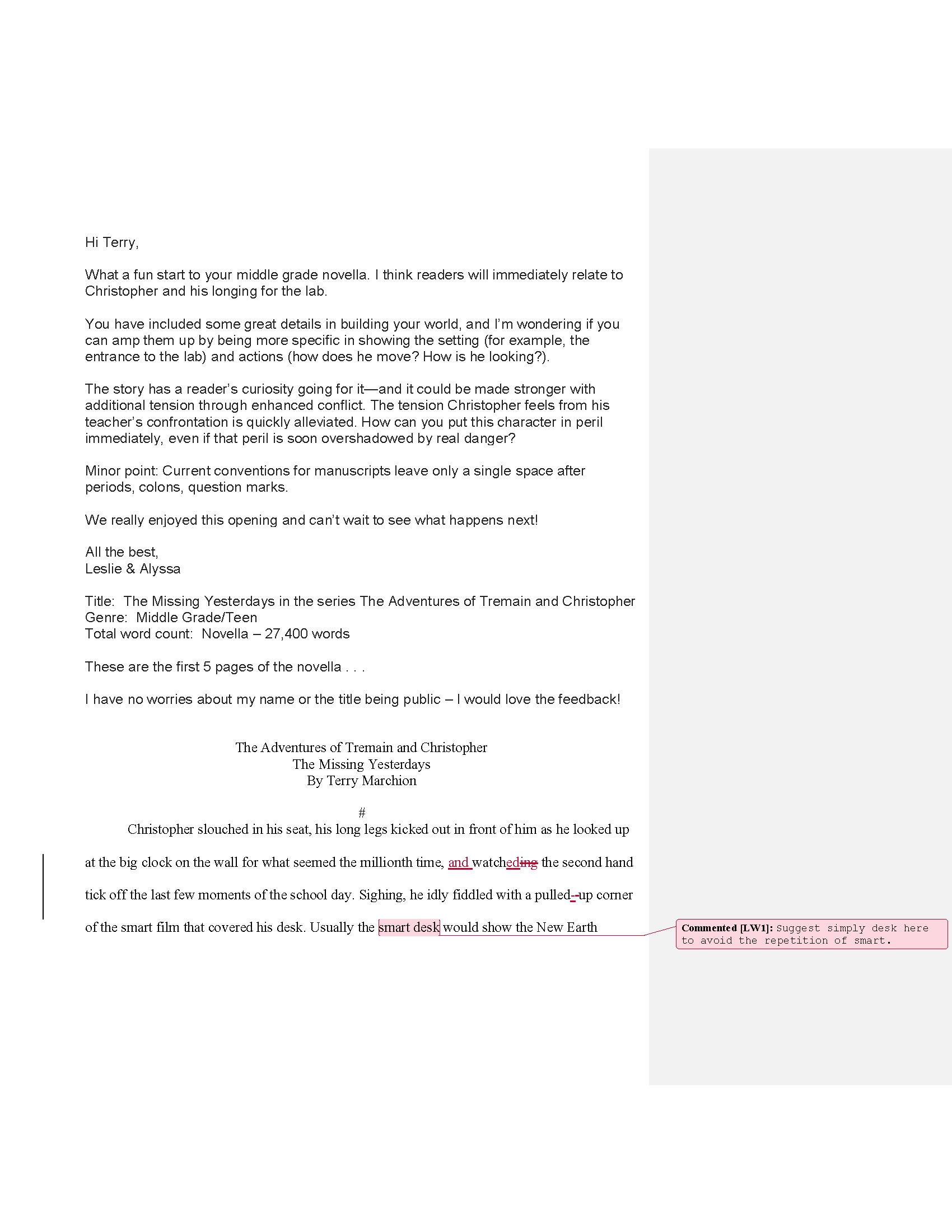

Episode Description

In this episode, Leslie and Clark critique the opening pages of Hiraeth by Robert Fritz Gaston, an as yet unpublished family saga novel. They discuss point of view, tense, introducing characters, and characteristic moments.

Warning: NSFW! This episode contains some adult language.

Listen Now

Show Notes

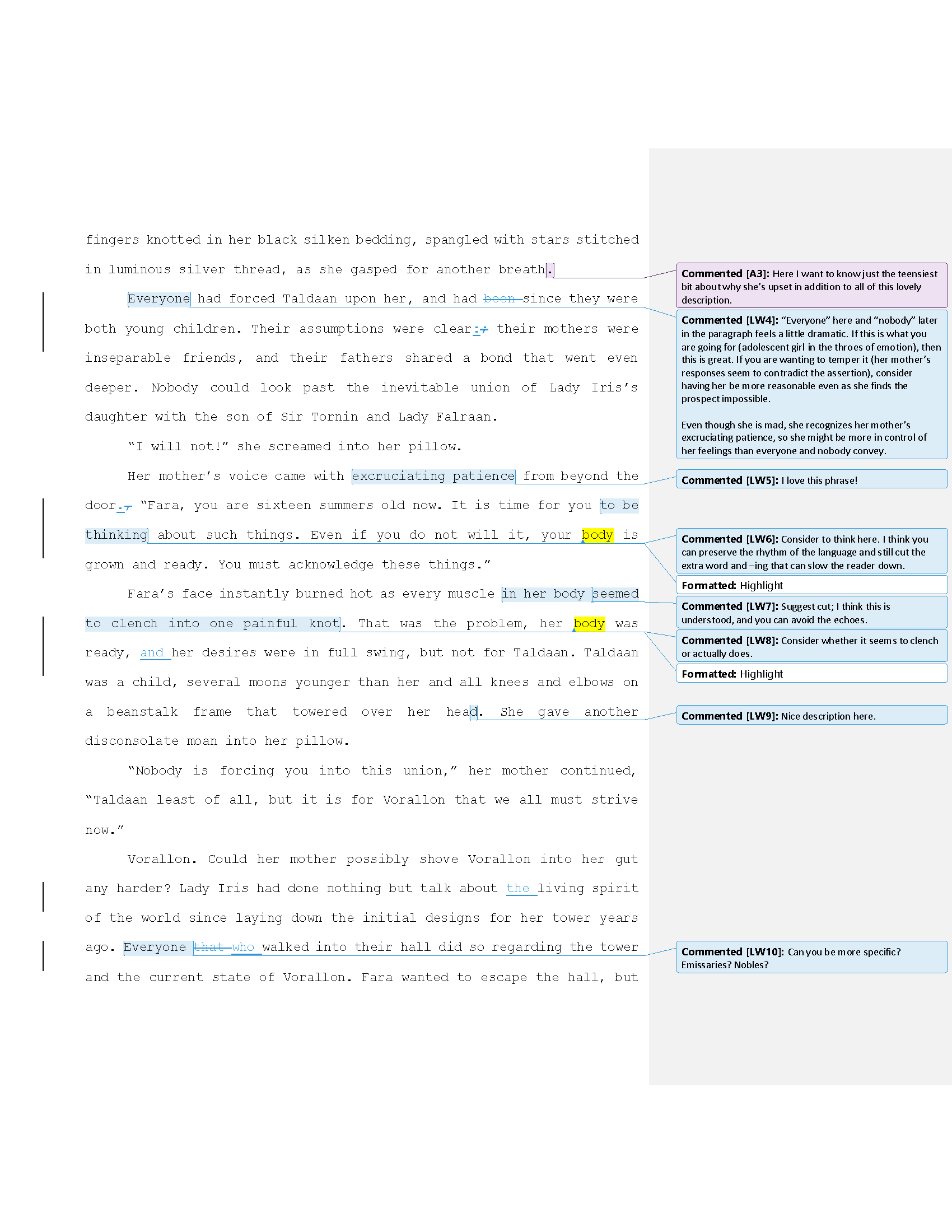

“The Characteristic Moment is a work of art. We can’t be content to open with our character doing any ol’ thing. We have to select an event that will: Make the protagonist appealing to readers, introduce both his strengths and his weaknesses, and build the plot.”

Editorial Mission

A characteristic moment tells the reader right away who your character is in the briefest span of time (number of words) in a way that connects to the plot before life changes as the result of said plot. It also allows the reader to compare it with another moment at the end of the story that demonstrates how the character has changed. It should show his strength and his flaws. That is a lot of heavy lifting for one moment in a story to do. But you can craft it!

Make a list of your character’s defining qualities. Everything you can think of. Strengths, weaknesses, what he wears, how he talks, the way he looks at life, good habits and bad, the way he treats people, etc. From that list pick the top three that are related to what happens in the plot and write a scene that demonstrates those top three things.

Want to see an example of this in action? In the opening scene of this story, William’s family gathers for a photo. Everyone looks “clean-cut and poised.” Where is William? He is hiding out having a quiet drink and smoke behind the trellis. We find out later in the scene that he is wearing the same outfit he wore for the last photo, and it’s a bit tight. So we know that William doesn’t quite fit in with the family in at least two key ways: appearance and caring about appearance, showing up for things that don’t seem as important (contrast with how he shows up in the next scene, and smoking).

Do you want editorial missions sent directly to your inbox?

Sign up below to join the podcast club and you'll never miss an episode—or an editorial mission—from the Writership Podcast!